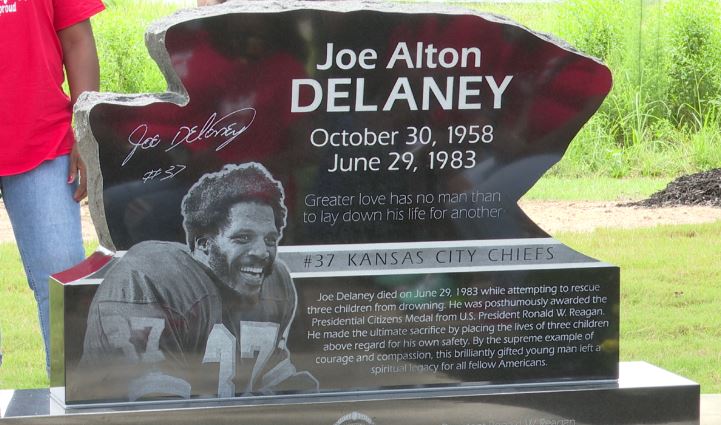

The Strange Death of Joe Delaney

Thirty years later, few remember the little man from Louisiana, running back extraordinaire for the Kansas City Chiefs for an astoundingly brief two seasons. But when he died, suddenly, on June 29, 1983, my impossibly small world was inexplicably shattered, despite being neither a fan, nor even a casual follower of, my team’s AFC West rival. Still, the circumstances of Delaney’s death were so grim, so needlessly senseless, that I couldn’t wrap my mind around it.

Despite not knowing how to swim, Delaney jumped into a two-acre water hole (with a depth of twenty feet) to save three screaming children, only one of whom managed to survive. Why would he do it? Why would this star athlete, one with a Rookie of the Year award already under his belt, risk it all for strangers, knowing it was futile from the start? Was he suicidal? Depressed? Drunk? Then and now, no part of me could comprehend an instinct for true selflessness.

Delaney’s arguably reckless act secured him a Presidential Citizens Medal, as well as a permanent home in the Chiefs’ ring of honor, but the expected what ifs remained; unanswered questions about a rare talent who never had the opportunity to disappoint. He went out on top, a legend, never having to limp for his supper, or block out the roar of outrage from a fickle fan base. Only greatness, then an even greater silence.

For me, it was always outsized and exaggerated; a moment not unlike the Kennedy assassination in its ability to create a distinct, tangible then and now. Of course, I now know it was little more than a brave man trying to do right, quietly dying on a sticky summer day, so ordinary as to be banal, but for a boy of ten, for whom football meant the breath of life, it forever challenged the idea of heroic immortality. The larger than life were not only vulnerable, they could be snatched away in an instant before their work was complete. The rich and famous had always died, of course, a few of which might have actually mattered, but this was youth and strength and promise, all at once dispatched with a uniquely brutal indifference.

In the years since, numerous NFL stars have died during their glory days, from Jerome Brown to Derrick Thomas, but Delaney was the first. Not ever, of course, but he remains the most indelibly marked on my memory. I still recall how I heard, what I felt, and the curiosity of earning an emotional scar for a man I had never met. Perhaps it was as simple as this: the greatest tragedy of all is not dying too soon, or at all, but ridiculously, and without sense. We all had to go, and yes, I knew that at ten, but from that point on, I was determined not to exit with indignity. Cancer, heart failure, stroke – all were acceptable somehow, so long as my final goodbye wasn’t preceded by an avoidable silliness. Maybe, on that long ago June day, were the origins of my near-pathological aversion to risk, my belief that a failure to try would, at the very least, ensure an avoidance of failure. It’s a mad delusion, of course, but never underestimate the power of example.

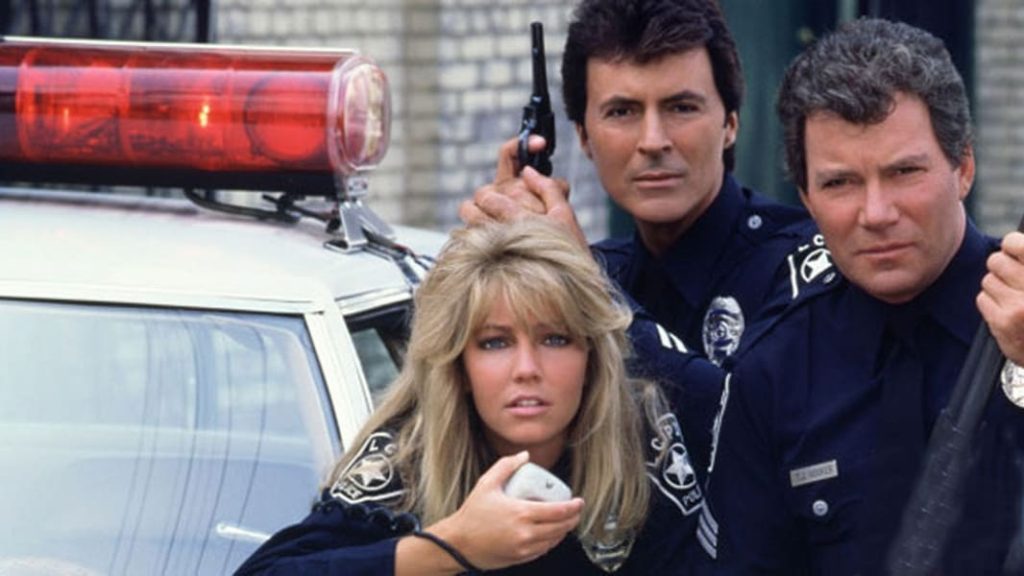

T.J. Hooker

The Los Angeles of the early 1980’s was, if you believe the show (which I did, implicitly), the most dangerous patch of ground in the world. Every single minute of the day, like clockwork, someone was being robbed, stabbed, kidnapped, or shot between the eyes. And god help you if you were a woman. Not only were the odds even money of being brutally raped in your lifetime, they weren’t much better on a daily basis. Every time you left the house, went to work, or (god forbid) decided that today was the day to get dressed in a leotard and set out for a bit of aerobics, you were at risk, doubly so if you added leg warmers.

LA’s special brand of hell was teeming with serial killers, Freudian head cases with mommy issues, and more nutjobs per square mile than the previous champion, 1970s New York. No one could possibly stay ahead of the body count, so it stands to reason that the powers that be decided to let four, and only four, officers (reduced to three by the final season) handle the unimaginable caseload. Other police personnel wandered about, of course, and the station’s din was unmistakably filled with phone calls and typewriters, but no one really seemed to be working. William Shatner would have to save the City of Angels all by himself. Like we’d want it any differently.

It might seem strange, perhaps blasphemous, to admit that my first encounter with Bill Shatner was with T.J. Hooker and not Star Trek but blame my local TV stations for not carrying reruns of the latter until my high school days. Before that glorious sci-fi circus upped my nerd quotient considerably, ensuring that my virginity would remain a firm reality well into my twenties, I had to accept Captain Kirk as a mere officer of the law, riding car hoods and chasing punks rather than dancing between the stars.

But it was meant to be. Trek would always remain the far better show (teleplays by respected writers, rather than cop drama clichés submitted on cocktail napkins), but I never watched it for the science of it all, anyway. I loved the torn shirts, fight scenes, and inevitable screaming matches. If a message or two snuck through, I wasn’t all that interested. There’s a reason why the episode with the Gorn remains a favorite. But T.J., man, he was all about the action. And what’s with everyone calling him Hooker, anyway, including his own ex-wife? I assumed his initials stood for Thomas Jefferson, or Timothy Jackson, but no one was about to spill any secrets. The show even used the term “prostitute” religiously to avoid any confusion.

Future stars like Sharon Stone and David Caruso stopped by on occasion, but they were only cool in retrospect. At the time, I was just tickled to see Jim Brown, especially when he went way against type and played a total asshole. Even better, he portrayed the owner of a downtown gambling den who screwed white people out of their money with marked cards and shady dealers. Needless to say, he’d end up hanging on the landing gear of a helicopter while trying to slap Shatner silly. Leonard Nimoy even made an appearance, and while I knew about Spock, the overall unfamiliarity with the character made it less meaningful when his crooked cop tried to frame an allegedly guilty man after he raped the shit out of his daughter.

It was fun anyway. Rape was on everyone’s lips back then, but like so many shows (see: The Facts of Life), it really didn’t seem to do that much damage. Maybe it was just like bad sex, after all. Unfortunate, but not traumatic. Either that, or LA women were strong as hell. Even Heather Locklear, who spent more time tied up in fleeing vans than any TV character in history, while not actually penetrated, kept up the toothy grin in the face of unchecked brutality. After a dozen near-misses, she still signed up for the massage parlor sting operations.

The ultimate genius of the show was its simplicity. There were bad guys about, and they could be spotted a mile away because they were stupid, obvious, and wanting to get caught. They hated women because they hated their mothers. They raped because they were raped. They killed because they were brutalized by the jungles of Vietnam. Clean and easy, without all of the excuses from social workers and civil rights organizations to get in the way. Still, this was no reactionary parade.

Almost without exception, the criminals were white, with the occasional black or Hispanic thrown in for color. LA hadn’t become Mexico by this point, and there wasn’t yet a laughable political correctness to distort the facts. What political content remained stayed in the realm of law and order. Hooker hated the feds, of course, because they botched investigations and hogged all the glory. Beat cops, “local authority”, were preferred over the top-heavy bureaucracy. And while women were all destined for the slab because of blond hair, big tits, and an obsession with street life, the men fared little better, as masculinity often connoted inherent violence. And if you had a mustache, well, that all but tipped the audience to your sadistic bent.

As I said, I was sold on the action. One of the many running jokes of the show was Hooker’s propensity for wrecking cruisers. Sure, he dented a few, but above all, his cars ended up in a fireball. It’s no exaggeration to say a motor vehicle blew up at least once per episode, often after little more than a low-speed meeting with a trash can. Now and again, we’d get two flaming cars at the same time, like the one episode where Vince Romano (the incomparable, forever young, Emmy-worthy, and current Twitter buddy Adrian Zmed) feared he might be blind for life because Hooker thought it was wise to continue driving a burning car for at least twenty miles, rather than pull the fuck over.

Cars also flew high in the air, people jumped through windows, and numerous characters were run over, thrown off roofs, and strangled. The show wasn’t even above killing children. But it was hostage-taking that ruled the day. In hospitals, stalled elevators, and seedy motel rooms, the helpless and the deranged were locked in a sick dance that only Hooker and his unfailing instincts could ever hope to break apart. Even when he died (and he did, seemingly), he was simply at rest; an unbroken, recently divorced warrior who didn’t seem to mind that his ex-wife was played by three different actresses.

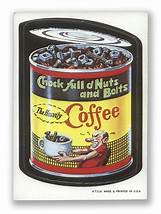

Wacky Packages

Challenge your average third grader about what he or she finds funny these days, and after sifting through the expected Twitter tales, crude sexual references, and cruel putdowns that pushed friends to the brink of suicide, you might get the standard fart jokes, animal noises, and racial tirades learned from unemployed fathers. All have the capacity to tickle an adolescent funny bone, of course, but during Reagan’s salad days, boys like me preferred the succor of Wacky Packages. Before the internet made every conceivable outlet for humor both ubiquitous and overplayed, we had to dig through whatever the free market saw fit to bestow upon our increasingly vital demographic. Sure, most of what passed for distraction was inane fluff, fit for savages rather than sophisticated young minds, but on occasion, we were handed a golden opportunity to be part of a special club. The half-wit down the street was fine for Smurfs or knock-knock jokes, and the burgeoning jocks, well, they could be satisfied by a burped alphabet song or two, but we the people, the privileged class, deserved a special handshake. We wanted wit, cleverness, and parody, even if we had no idea what any of that entailed. Call us ahead of our time.

What were Wacky Packages, you might ask? Only the most outrageous, subversive stickers ever produced, even if Topps wasn’t exactly working hand-in-glove with the IWW. Apparently, they had existed in some form for years – and still do, against the odds – but my time coincided with an early 1980’s resurgence, when the world’s leading baseball card operation knew the kids were not only alright, but wanting to laugh at familiar products and brand names in a new, crazily reconstituted form.

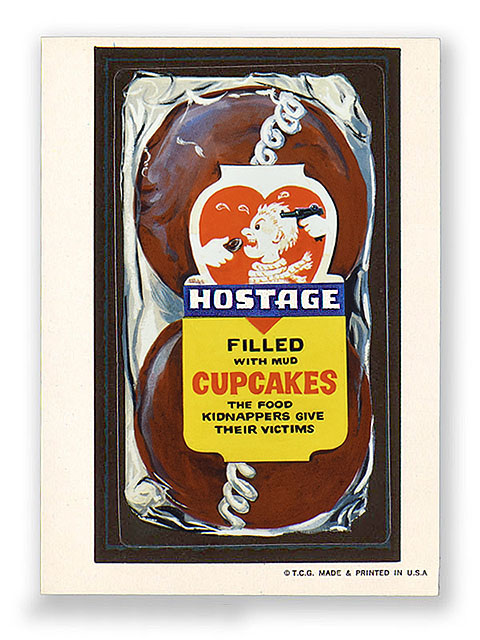

And so we were. With artwork so off-the-wall it could only have sprung from a studio of the damned, the stickers were emblems of revolution, a frenzy of rebellion that threatened to angrily expose the complacent consumerism to come. Mr. Clean? We’ll give you Mrs. Klean. Chock Full O’ Nuts? We’ll add “& Bolts” and just walk the fuck away. Have a sweet tooth? Try Hostage Cupcakes. Need a little butter on that? Try a dollop of Land O’ Quakes. A side dish with dinner? All we’ve got is Rice-A-Phony. And if you’re taking a shower, don’t forget your Head & Boulders. Not even peanut butter was safe. The counter is bare, save the Peter Pain.

I bought pack after pack, loving every one, and greedily amassed a treasure trove envied by a host of imaginary forces dead set on spoiling my fun. In contrast to the bright and bubbly packaging of the grocery store, Wacky Packages dared to be ugly and mean, where the last thing anyone wanted to do was glimpse the product within. The art was meant to turn you off, hopefully towards a greater, more lasting meaning (but you’d still love spending money on Topps, of course). Even our beloved candy was given the once over, and if anything, every phony product revealed the hidden truth that what we were putting in our mouths was already garbage, so why not be more frank about it? It was my first taste of cynicism, and I liked how it felt. The baseball cards would never be this wickedly fun.

Leave a Reply