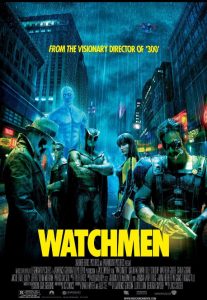

Given the troubled production history and the reputation of Watchmen as unfilmable, it is remarkable that this ever came to the screen, and was able to reduce the expansive narrative into a digestible chunk. Though the comic book (‘Graphic novel’ is a stupid term – if there is nothing wrong with ‘comic book’ then there is no reason to be ashamed of it) was hugely influential on the industry, and the book has garnered a sizeable fan base, the film should be judged apart from the source material. This is fair for two reasons: one, any work of art should be capable of standing alone, and two, I have not read it.

Watchmen is a loud and chaotic film that should work in theory but comes off as a philosophical mess. Though I am unaware of how much of this is due to director Zack Snyder, the film is far better than the execrable and sexually confused 300, and either indicates the strength of the original story or a welcome maturity in Snyder. Watchmen deals with a world in which superheroes do indeed exist, wear masks and ridiculous costumes, and exercise an influence on world history. The heroes turn out to be deeply flawed, self-indulgent, and turn out to be just as capable as regular people at worsening every imaginable problem. A quickie montage reviews the advent of the superhero in the 1920s, fighting crime, starting on a small scale. World events do not change appreciably apart from Richard Nixon winning reelection three times and winning the Vietnam War with their help. Superman, notably, was ordered by his father not to alter the course of human history, so as to keep the achievements and failures of humankind within themselves, rather than be dependent upon an alien force.

In Watchmen, the heroes storm a Vietcong beachhead in a mockery of the scene in Apocalypse Now, flattening the enemy soldiers with ease. That this attains nothing apart from symbolic victory is made clear quickly, thanks to the Comedian. As the most vocal of the Watchmen, he retorts to the question “What happened to the American Dream?” with a resounding “What happened? It came true!” This against the backdrop of an irreversible descent into moral and political morass by the 1980s. Drug use, pornography, and murder are rampant, and the Soviets and Americans are preparing for a nuclear war over a dispute in Afghanistan, and the Watchmen have been outlawed. Whether their ban is due to their quaint attitudes about justice or their purposelessness in the sewer of human nature is not made clear, but this is no simple world for superheroes.

The story unfolds as the Comedian is murdered, tossed out a window by an assassin. Rorschach, a reactionary misanthrope with a mask of shifting ink blots, is on the case to find out who wants the Watchmen dead. Ozymandias, the world’s smartest man and massive corporate kingpin, is working to provide free energy to humankind so as to make war itself obsolete. Nite Owl, an annoying asshole, has some function involving being the cranky devil’s advocate and straight man to Rorschach. Lastly, Dr. Manhattan is the only one with true superpowers, having been converted by Whatever Technology into a glowing blue form that manipulates matter on a particle level and exists on multiple planes of location and time; as such he lacks any real connection to humanity since he cannot die and can exist on any plane.

Though wildly out of place amidst more practical superheroes, Dr. Manhattan is the sort of figure a comic book writer would develop if giving quantum physics some thought. He can kill humans without an effort, lay waste to regions in massive bursts of energy, teleport to Mars and build a city, walk on the sun, and destroy all human life. This literal deus ex machina becomes a symbol of American invincibility, and results in pushing an overconfident Nixon to the brink of war. This places the utility of a crime fighting force that operates outside the law in sharp relief, and questions the attachment one has to people who either take such involvement for granted or holds it in contempt.

This brings me to the central weakness of Watchmen – the book was unfilmable not only for a dense story and tremendous length, but for its character as a meditation on the darker side of human nature and a superhero or super beingÂs inability to introduce it to the brighter side. This does not strike me as a bone-crunching action film, and so the action sequences appear tacked-on, awkward, and ultimately padding in a movie that stretches to 164 ass-numbing minutes. As such, some of the quiet moments can be affecting, and punctuate the violence with greater meaning.

There are other considerable flaws in pacing and content – with such an expansive story to tell, and imminent nuclear holocaust, I could not give a toss about whether Nite Owl and Jupiter get it on. 300 had the same problem, with ample padding despite the story of Thermopylae being essentially a small group of men methodically stabbing thousands to death in a mountain pass. Keep it tight, at the peril of enraging a public with engorged bladders. The film is a dependably reactionary fantasy in that torture unfailingly yields useful and accurate information, and that there is no problem that cannot be solved by beating large numbers of people senseless. Then, there is the endgame, which is genre-defying in its contentment with pointlessness. You see, the only way to deal with a suicidal human population is to threaten them with a massive event of slaughter, signified by a sort of particle explosion that disintegrates New York City, blame it on Dr. Manhattan, and kill off the good doctor so mankind eschews nuclear ambition. More on this in a moment.

Even from a philosophical standpoint, Watchmen runs itself amok. Ozymandias is a pacifist, and so he plans to exterminate 15 million people in order to create such fear in the remaining people – fear of Dr. Manhattan – that they cease nuclear stockpiling. That the smartest man in the world had not considered that once time has passed, even fear of annihilation loses its vigor, and the human need to kill his fellow man resumes its course. The plan he formulates is so perfunctory and seemingly spontaneous despite his idiotic villain lair that it strains belief.

Dr. Manhattan is so utterly detached from the chaos and mess of human relationships that he is a purely intellectual form, yet his emotions are easily manipulated. He would rather create life in a distant galaxy than deal with the complexities of humanity, but decides to ace a former friend due to a difference of opinion. Nixon is fully prepared to launch a preemptive nuclear strike against the Soviets and accept the loss of the entire east coast of the United States, yet drug use is the worst societal ill of the Watchmen world. Overall the purpose of having the Watchmen around at all is given a cursory treatment, leading one to wonder if this gargantuan story and what is in many ways an immersive film is really worth the trouble.

Rorschach presents the worst flaw in the film, though not for lack of effort by Jackie Earle Haley in a film-stealing performance. He is a cynical fellow who decries liberal thought and weakness, yet is ready to die in an instant to defend mankind, which is inconsistent. Then, he insists on informing the world that the city-leveling blast was a ruse, and the resulting peace instilled by fear is a lie… and so Dr. Manhattan vaporizes him. This bothered me intensely, but it took a while to realize why. Rorschach represents the dispassionate value of information, which dovetails with his identity as a detective. He despises humanity for its self-destructive proclivities, but this is not borne of some intrinsic hatred as much as observation. The human race does not acquit itself of the charge of inhumanity very well.

The resolution of the film depends upon a massive lie, that Dr. Manhattan awaits an opportunity to destroy all life if the people of Earth continue to fuck up, and that peace would evaporate if people knew the truth. So Rorschach was killed to preserve the gossamer-thin cover story that was bound to fall apart anyway. The enemy then, of humanity is not itself or any particular philosophy… it is information. The self-awareness of human nature and its penchant for cruelty and degradation is what threatens humanity’s future. Otherwise, there would have been no need to dispense with Rorschach as a loose end. This dim view of knowledge as a destructive factor, rather than the one thing that may redeem a deeply defective species brings the thoughtful questions in the ether to fall to the floor with a dull thud. Instead of the dull ache of uncertainty, one is left with a resounding apathy.

Perhaps Watchmen as a comic book is superior to the film, which given its length, depth, and reputation, I have no doubt that it will be. Many of the philosophical questions mentioned above would be given a better treatment in a work of enormous breadth, and responds well to a more subtle treatment. Zack Snyder is a sledgehammer where a syringe would work wonders.