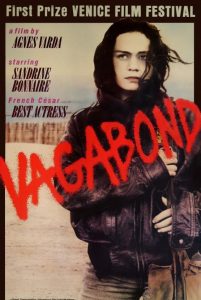

How does one conduct a character study of a complete void? The human soul is elusive enough when it has emotion, connection, and interacts with those who share its space. When that soul retreats deeply and sheds aspiration, joy, and intellectual craving, then a standard investigation into that marrow would be halting, and make for an aborted cinematic experience. Fortunately, Agnes Varda is at the helm of this subject, and since her advent in the French New Wave, she has been as difficult to characterize as the lead role in Vagabond.

Mona is a drifter, in every possible sense of the word. Her history is implied during her brief and cursory interactions with people who pass through her life, but it ends where it begins – with her death and what is known about her. She is found frozen in a ditch on the edge of a wine farm, and as her body is bagged up with no identity, the questions begin about how she came to such a ignominious fate. Thankfully there is no Citizen Kane style sleuth to interview the various beings who passed her by; it is doubtful anyone would care about another anonymous death. Rather, the individuals who interacted with her talk to the camera as if they have become aware of her passing, and spend but a moment wondering who she was. The artifice becomes art, and we are free to become lost in the narrative as scenes from her life play before us.

Her name was Mona, and all she owns is on her back. She walks, hitchhikes, and camps where she can, squatting in abandoned buildings, bumming smokes from drivers and avoiding prostitution as a means of survival. Little is explained, leaving the viewer free to piece together what they can, and try to understand Mona. She encounters various people in succession, and inexorably moves on to some unseen horizon.

She encounters a college professor who specializes in tree diseases, particularly a fungus that destroys native trees of France in the Marseilles region. The two could scarcely have less in common, but the professor works alone for the most part, and appears to enjoy the company despite Mona’s stench, chain-smoking, and poverty. They drove about together, she shares champagne, offers her a place to sleep. She is an academic, and regards Mona almost as a curious puzzle of the human condition, rather than one with whom she has a genuine connection. When asked why she dropped out of her job and her place in society, Mona’s cryptic answer is, ÂChampagne is better on the road. She has taken root in the car, but will feel free to disappear as soon as the impulse guides her. No need to speak to anyone unless she runs out of cigarettes.

Mona runs into a small farm run by a hippie couple who till the land, make cheese, and eke out a living. They offer to train her to become a farmer, provide her with more than enough land to raise enough food for a year, and a trailer to shelter her from the elements. Even being her own boss, though, is more than she can take, and she settles for stealing food and eventually leaving for the solitude of the road.

The farmer throws her out, understandable given her unwillingness to help, brushing off her protests with, “You’re a dreamer.” Anyone who lives at such an extreme is required to be a dreamer, aspiring to an idealized life that they cannot attain through practical means. Whether Mona’s decision to push on and live without a safety net or place to land can be explained by a past trauma, bad wiring, or whatever, Varda does not allow for pat explanations. This is human behavior at work, without the intrusive hand of a plot-minded screenwriter to spoil the show.

Mona was once a secretary, but could not stand the life of compromise that earned a place amidst a society; she spurned this entirely for a life upon the road. Though she depended on the largess of strangers to stay alive, this was likely due to her lack of skills and impulsivity that led her to strike out on her own before acquiring survival skills. Much like McCandless from Into the Wild, she lived on the edge, only a vague misstep from disaster. All it would take is the wrong word or an encounter with the wrong person, and her life would end badly. Such is the risk of freedom, and some are better at it than others.

Mona was once a secretary, but could not stand the life of compromise that earned a place amidst a society; she spurned this entirely for a life upon the road. Though she depended on the largess of strangers to stay alive, this was likely due to her lack of skills and impulsivity that led her to strike out on her own before acquiring survival skills. Much like McCandless from Into the Wild, she lived on the edge, only a vague misstep from disaster. All it would take is the wrong word or an encounter with the wrong person, and her life would end badly. Such is the risk of freedom, and some are better at it than others.

With absolute freedom, you are free of any connection, responsibility, and ownership; but you are also entirely alone. This is not to be taken lightly since humans are gregarious animals – despite our need for privacy, we lose powers of language, thought, and eventually sanity if we live in solitude. With total denial of freedom, we benefit from being locked into a system, from large classrooms to being one of millions of office drones, to a face in a nursing home crowd until buried in a vast cemetery.

Somewhere along that axis of freedom and responsibility our lives will settle, our degree of compromise determining just where we drift. Our inability to understand that compromise is what can careen our lives off the intended course. Where this drifter lies upon this axis is not made clear; in one scene she donates blood, but has no interest in the food, and does not make money. There is a desire for human contact, but she no longer knows how to achieve this.

Varda’s eye for composition is stellar, and at times there is little need for dialogue. In a brief shot, Mona’s hands momentarily appear to be reaching for the hand of another woman across a table. A moment, and she withdraws – all you need to know about her character. In another extended panning shot, Mona walks alongside a wall painted in vertical stripes that occupy the screen. Brown and pink, alternating, and the effect is disorienting, as if the implication is that fortunes can and will change violently from moment to moment. A startlingly photographed tree is destroyed by a fungal disease, rotten from the inside. Even a mighty tree, with its strong roots is not immune to succumbing to the elements. Her journey is ever watched with panning shots, usually from right to left, as a psychologically weak and lost direction. But then, is it a journey if there is no destination?

She interacts with a migrant worker, another drifter, an avaricious family who await the death of their mother; each sees her through a lens of their own desires. For example, the professor studies trees, and is fascinated by Mona’s lack of roots. She lets her off on the edge of a forest, one she knows is dangerous and full of drifters, but does not realize the danger until she is nearly electrocuted in her home. The hippie farmer rejected the capitalist system to farm, and considers only how Mona refuses to work in any system, even her own. A maid throws Mona out of her house when she suspects her boyfriend might cheat on her, later considering Mona’s fate when she herself is fired from her job. A homeless drifter who stays with her for a few days is surprised to find that she does not want to stay with him. Always the protagonist is viewed from the perspective of others.

Perhaps this is the only way to regard others; or perhaps the character’s emptiness and solitude make it impossible to see anything from her point of view. And perhaps a theme would be the impossibility of truly knowing others except in how they relate to oneself.

Little is explained as such, yet a complete explanation is implied. This is no sentimental look at life on the road. There are no quirky characters, or wise old men who have seen it all. Boredom, suspicion, and hunger are the rule, perhaps with the occasional respite of pleasure. There is only the grind that starts anew each day, for a place to sleep and food to eat, a struggle that begins with each morning light. Fail but for a single day, and your body is found the following day in a frozen ditch, with only a fractured narrative left behind. As we watch her smile faintly while listening to the radio, we wonder just what is behind those eyes, and what compels her on this bleak road. There are few clues, other than desultory words, a need for food and shelter, occasionally sex.

As she descends through loss and desperation, we see no ambition, no desire for something better, a place to live, a person to love, a moment of wonder about the mysteries of life… no desire for anything, really. Her identity consists of her name, and even that could be left behind as easily as her job, family, and anything that could define her stay upon the Earth. I saw my own fears of solitude and rejection in her character, as anyone employed is but a firing away from disaster. In a way, I also considered whether my life is indeed any more enlightened or important than hers, given that we will both decompose in the same amount of time, without much left behind to define us in our absence.

As time passes, you become aware that you are just one more character in her life, like the others you have seen, projecting upon Mona your own perspectives, fears, and prejudices. And in the end, faced with a body frozen in a ditch, you have likely learned more about yourself than about this random drifter. Is it even possible to understand other people? The question is impossible to answer, and Vagabond does not attempt. Even this theme is implied, and the terminal fade echoes the closing thoughts of Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon: “It came from afar and traveled sedately on, a shrug of eternity.”