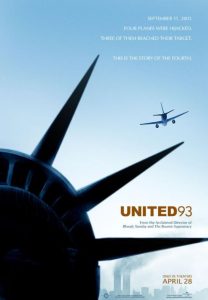

If I were a slave to predictability and the expectations of the Ruthless faithful, I would blast United 93 as Sean Hannity’s fevered wet dream; a jingoistic call-to-arms that re-imagines the entire “war on terror” as the brave, unflinching efforts of a few all-American souls aboard a doomed aircraft. I would assail the director, Paul Greengrass, and the entire freshly scrubbed cast, as mere pawns in a work of such shameless propaganda that viewers are all but compelled to stand at attention and weep uncontrollably. And of course, we’ve all read the reviews, many of which hammer home the right-wing line that yes, this is what it’s all about, and let us all hear the call of the film and move forward with flags held high, hands over hearts, and uniformly shouting prayers to the heavens that George W. Bush has been sent by Jesus to lead us at this fateful hour. And yet, while such an interpretation is entirely possible, it is nowhere near my immediate, visceral reaction. For rather than see this film as part of a larger cause or political movement, I am determined to see it only in its narrow context, much as the passengers would have assessed the few moments left to them as the plane careened out of control. On that basis alone, United 93 is a supremely confident work; a masterful account of several hours that no one will forget, though most will misinterpret and exploit.

If the goal of the film is to place us inside the fuselage of that plane and on the ground as events went from confusing to horrific, it succeeds on all counts. By using the time-tested “verite” approach, the film becomes more of a document than a standard piece of entertainment, as we are as twisted and contorted as much as anyone on that day. By giving so much attention to small, seemingly insignificant details — waiting in the terminal, shaving, reading the paper, chatting with the tower — we fully understand that momentous events always begin with shattering banality. As air travel remains the safest method of transport, the journey aboard a jet has become an unthinking ritual on par with making a sandwich. Chickenshits like myself continue to feel uncomfortable in the air for no reason other than a perceived loss of control (if my car acts up, I can pull over), but few things in life are as routine as climbing aboard an MD-80 or 737 and hitting the skies. On occasion, a jet will slam into a mountainside or catch fire during takeoff, but as even minor incidents make the papers, the odds of experiencing even major turbulence approach winning the lottery. So imagine how we all felt when not one, but four planes sent hundreds to their graves in a single morning; all with the suddenness that only true horror can bring.

Despite knowing what will happen to the flight in question and what it would launch across the globe, my mind was in and with that one plane exclusively. This is even more astounding when one considers that for the majority of the flight, nothing out of the ordinary happened. There’s the predictable tension, yes, but this served only to enhance in the film what would otherwise go unnoticed. I scanned every face, every seat, and every bead of sweat, as I felt this was the only opportunity to empathize in whatever way I could. Needless to say, no film — regardless of the talent involved — could ever really approximate what it would be like to plummet to the ground knowing one is about to die, but somehow this was the best that could be done. Perhaps I was so damned riveted because I am extremely (and irrationally) nervous on a plane, and yet that’s enough, for if my involvement were due to patriotism or hatred of the terrorists, then I would feel ashamed in retrospect. Several people applauded when the passengers stormed the cockpit, but that seemed as pathetic as it was futile. These people still died, and those who didn’t smash the cockpit door still clung to their seats helplessly as the plane crashed nose first at full speed. Yes, these people were brave, and selfless, and had more courage than I could ever hope to muster in far less trying circumstances, but I could think only of how they spent their last few moments alive.

Did I say brave? Do I also seek to honor those ordinary lives and what they did that day? Absolutely. And yet, my admiration is selfish, as I am not so concerned about saving lives as I am the symbols of either the Capitol or the White House (this film believes the target was the former). Screaming, burning Congressmen would cause me not a moment of grief, but had the buildings themselves been destroyed, that loss of the very seat of power might have been a death blow. Certainly, we’d move on as we always do, but I would be humiliated and crushed, as the historical importance far outweighs any immediate loss of life. In this way (and to feed the idea that I am a heartless bastard), I had no real sadness regarding the World Trade Center or even the Pentagon. No, I won’t soon forget those who leapt to their deaths (and that hideous, awful sound of impact), but the steel and glass are, in fact, utterly meaningless. Nothing vital to the national narrative took place in those towers, and another institution of commerce could be erected without anyone really noticing the difference. It’s the same sort of feeling when I visit a dying city like Buffalo, New York and learn that the spot of President McKinley’s assassination is now a discount store. I firmly believe that in order to remember (and yes, I understand that fewer and fewer people want to think accurately about the past, if at all), we must have a physical location on which to ponder distant events. Alas, kitsch often reigns at such locations these days (Ford’s Theater, for example, might as well open a hot dog stand in the lobby), but it still fosters a great deal of emotional power to inhabit the location where the stream of tedium that defines so much of our days was temporarily interrupted by the unique, the defining, or the powerful.

The film also soars in its decision to stay away from the “human interest” garbage that so often sends a movie like this off the rails. We hear snippets of cell phone calls from passengers to loved ones, but only from one end, as it should be. Had the film cut to the families on the ground, it would have been about them as well, and for what they went through in their final moments, the passengers deserve exclusivity. We get no background, no biography, and, as stated, no larger context. Much of the dialogue had to be invented, of course, but it always remains believable. In other words, passengers and crew talk about the immediate — what’s going on, what can they do, what might boiling water do, etc. — and not philosophical ruminations that put everything in perspective. Republicans might want these average folks to be standing tall for King and Country, but nothing of the sort could be pulled from the film unless one is pre-disposed to apply politics to each and every moment of the day. Even the terrorists — deluded, childishly idealistic, and utterly poisoned by faith — are authentic and “ordinary”, rather than wide-eyed caricatures as imagined by a screenwriter with an axe to grind. They perform their perceived duty with ruthless efficiency, but we also see that, in fact, committing mass murder might not be as easy as it seems. That’s not to say that they were struck with a conscience in the midst of their deed, but it’s also bowing to reality to portray nerves, adrenalin, and happenstance as part of the mix. And as the official record proves, the attack on the cockpit was in fact delayed (for reasons that will never be fully understood), for had it occurred sooner, the Capitol may in fact have been destroyed. It’s this matter-of-factness that should alienate those who claim to support this film, as surely they would have been more comfortable with screeching banshees who possessed not a trace of personhood.

And so we swing back to why United 93 is a truly great work; a film that captures an event better than most films ever dream of doing. From the various control centers tracking the planes to the halted, nerve-racking conversations on board, the camera darts and dashes, never believing that any one person should take center stage. Even the now famous “Let’s roll” seems less a rallying cry than a trite substitution for “Okay, now.” And when those few pushed forward to the cockpit, they had no intention of saving civilization or boosting Bush’s poll numbers; they continued to believe that, just maybe, they could gain control (after all, a pilot — albeit of single engine planes — was on board). In the same way that the body fights for air or claws its way back from certain death, the survival instinct — easily the most powerful element of the human animal, as well as all of nature — demanded that these people, as long as they had a second of life left to them, try to stay alive just a moment more. Conservatives and hawks may see more to their act on that September day, but it’s enough  more than enough  that they tried to save their own skins. I admire the hell out of them for helping to preserve vital landmarks, but as that was never their intent, it’s only an “accidental” tipping of the cap, despite the result. And yet I do not believe that understanding this truth lessens their actions a single bit. Or maybe it’s a simple case of being impressed by anyone who wouldn’t be shaking with me under the seat.