Just about any scene chosen at random would be representative of this virtually wordless film that has been described as the greatest road movie ever, and not without reason. Rather than the standard journey filled with exciting chases, personal epiphanies, and resonant characters to portray an adventure of epic magnitude, Two Lane Blacktop is a flat and dry film that is so empty of meaning or direction that it transcends the genre and dares the viewer to find something of entertainment value within. Having driven across the country before, I can attest that doing so really is this boring, with nary a word passing between passengers as flat scenery moves past. Life is not split into chapters of great importance as much as going past moment by bleak moment.

The story, such as it is, involves two drifters in a souped-up car, and they are not in search of anything in particular, and their trip has no destination. This is Vagabond without the human connections (or lack thereof) or insight, but I feel this is intentional. The characters are dull, and lifeless, unable to establish connections that are meaningful, and unable to appreciate anything beyond merely existing. The nihilistic tone achieves grandeur in itself, up to the controversial and bravura finale that is more than capable as a statement on the meaninglessness of life without direction.

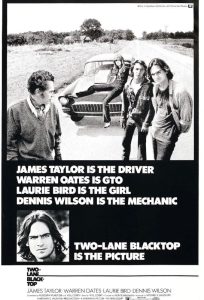

We spend the film with two characters, the Mechanic and the Driver, and they do not speak unless discussing the 1955 Chevy they drive from one road race to another. Driving and racing are conducted without joy or pleasure, and are little more than a way to earn just enough money to continue driving and racing. They have no home, except the Chevy they pamper and adjust constantly. Every time they stop for petrol, off comes the hood for a thorough examination in a wordless ritual. They rarely smile, the actors Dennis Wilson and James Taylor giving taciturn non-performances that capture the drudgery of survival as transients. Considering how little money they have at any time, it would seem alarming that any major engine failure would leave them on foot and unable to make repairs, but this would not unnerve the Mechanic or the Driver.

They do not seem to care about much of anything, and have no past or discernible future. They have no knowledge of anything that is not car-related, and so they cannot read a timeless classic of literature and gain an insight, watch a sunrise and appreciate its enduring beauty, or consider the cosmos and its infinite vastness. Their eyes are trained upon the road ahead, and with so little hope for anything resembling hope, it is probably best not to think too much.

The Girl? enters the picture, another drifter who hitches rides with anyone she can out of boredom or in the same search as the main characters for nothing in particular. The Mechanic and the Driver sleep with her, but are too reticent to understand anything about her. In one scene, the Driver attempts to reach out to her, perhaps out of affection, in teaching her how to shift the transmission of the Chevy. She is unable to do so without stalling the engine, and he is no good at teaching her, and so the impasse is reached. That she moves on is no surprise, as there is nothing here. She has yet to discover that there is nothing out there, either. The actress playing the girl (Laurie Bird, who also appeared in Cockfighter) eventually figured this out, and she committed suicide several years later.

The most expressive character of the bunch is GTO (so named for his chariot), as played by the immortal Warren Oates as a chatty compulsive liar who reinvents his life story with each hitchhiker he picks up. As much as the Driver and Mechanic, he has nowhere to go and nothing to do, apart from lying about his life as he runs away from it. At one point he does reveal that he has lost everything, his family, his job, everything but his GTO, and even that he is gambled upon without too much thought or racing experience. If I’m not grounded pretty soon, I’m gonna go into orbit.? Oates imbues his GTO character with a persistent sadness, and we are made to know that this is about as good as his life will get. The melancholiest monologue he gives is to another passenger about how he won this sweet car by beating a couple of punks in a cross-country race using a 1955 Chevy, while they used a GTO. He is more than aware of his life’s worth.

The minimalist conversations between these characters aim for a Zen-like state without the clutter of culture or perspicacity. There are moments for asides that suggest an end to this drive, as GTO gives a ride to a woman heading to a cemetery to visit a family member killed by a car, and a road accident caused by a drag race. Meaning everything and nothing, the drive continues. There is only the road and the speed of the Chevy, and as the Driver intones, You can never go fast enough. There is nothing else. There is a cross-country race for pinks, but this never becomes important.

In the fascinating coda, yet another small drag race is entered for driving money, and the Chevy accelerates, the sound cuts out, and the film slows and melts as if stuck in the projector. There has been much argument about the meaning of this, or whether the director was being unnecessarily cryptic, but like the rest of the film, this becomes a satisfying blank slate upon which the viewer can project their mood as influenced by this desolate film. The inarticulate characters, impotent in their ability to bond with any other member of their species, were profoundly melancholy from start to finish. We do not know whether the Driver won this race or any other race because it does not matter.

He and the rest would end up in a ditch soon enough, or run out of road in some fashion. This is life without any philosophy, no ambition to provide direction, and no hope of achieving anything apart from premature death as the only pleasant release. Whether one prefers the delusion of religion or the intellectual background necessary to regard the world and one’s place in it, it is impossible to imagine living without a guiding force of some sort. Or perhaps I have expressed my own delusion, in that there is something to hope for, even if it is so mundane as improving the lot of someone else’s life or appreciating cinema as something that exhilarates or informs. Maybe the Driver has it all figured out, in that there is nothing to fight for apart from an arbitrary goal that one’s skills can make possible.