“The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.” —Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

The Zone of Interest announces itself with a lengthy title screen dissolving to full black over the course of a couple of minutes, leaving the audience in utter darkness with Mica Levi’s haunting, primal score for an uncomfortable amount of time. It is a bold approach that draws the viewer in and encourages sharp attention to every detail onscreen and, even more importantly, to the incredible sound design. Writer-director Jonathan Glazer has stated, “There are, in effect, two films: the one you see, and the one you hear, and the second is just as important as the first, arguably more so.”

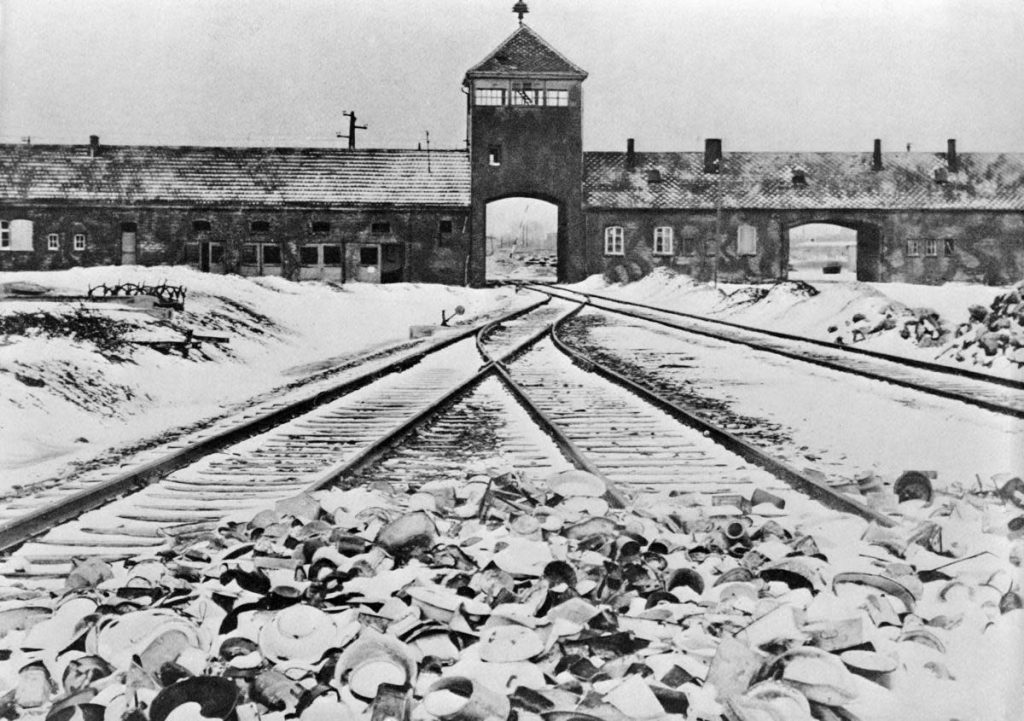

In the opening scene, sound and picture are together, as the Höss family enjoys a day out in the countryside, swimming and fishing. Birds can be heard in the background, the sound of a woodpecker foreshadowing the rifle shots to be heard in the background of their idyllic home, located in the titular euphemism just outside the death camps of Auschwitz. There they have a truly beautiful house and garden, but with the ever-present sounds and smells of the work Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) does each day: the shouts of the guards, the screams of agony and despair from the prisoners, the burning of their flesh and the constant dull roar of industry, and of course the gunshots.

Rudolf’s wife, Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) is more removed from the horror, and seemingly unaffected as she tries on the fur coats and lipstick of murdered Jewish women. In so many ways she is the typical homemaker, tending to her garden and doting over her baby, able to ignore the black smoke of slaughtered souls rising above the wall that separates her home from the horror that feeds and houses her children. She undoubtedly sees herself in the same way the more “benevolent” slave masters did in that other most abjectly shameful era in human history. Her housemaids “live well” in her home, but she is not above threatening to “have [her] husband spread [their] ashes.”

Hedwig’s visiting mother finds it more difficult to ignore the smoke, the smell, the sounds, though she expresses a barely veiled, vindictive joy at the knowledge that a Jewish woman by whom she’d previously been made to feel inferior has been rounded up for the camps. Ultimately, though, Hedwig’s mother finds the sleepless nights and burnt flesh in the air too great a sacrifice for the paradise of the Omelas that is their gorgeous home and garden. She leaves the zone in the middle of the night with just a note to Hedwig, who reads it and promptly throws it in the fire, a final solution to any problem.

Like its PG-13 rating, most of what we see onscreen is deceptively ordinary and acceptable. Shot largely on hidden cameras with natural light, Glazer’s film creates a disturbingly immersive portrait of a family working towards a better future, with a nightmare of torture, imprisonment and death just beyond their garden wall. The only blood we see is washed down the drain from Rudolf’s boots by a Jewish servant. The only evidence we see of the dead is the smoke in the air and the ashes being spread by another servant in the Hösses’ yard to fertilize the soil. The only time we are on the other side of that wall is a tight shot on Rudolf’s face from behind, the screams and shots so much louder than the constant background din we’ve grown used to, a tiny curl of black ash clinging to his cleanly shaven neck.

Perhaps the most chilling moments are the ones involving the children. In one scene, the younger boy plays aimlessly with dice alone in his room. The daily commotion of the camp can be heard through the window; a prisoner has been accused of fighting over an apple. “Drown him in the river!” an officer shouts, and screams rise and fade. “Don’t do that again,” the boy mutters with haunting nonchalance, as he continues playing idly.

Later his older brother, dressed in a child-sized officer’s uniform, picks on him by forcing him into the greenhouse and obstructing the door. He sits outside and watches, grinning, as the smaller boy bangs on the door and begs to be let out, then he mimics the hiss of gas being released with his breath. It’s a distressing reminder of how the seeds of monstrosity can be sown, one of many times one is reminded of Michael Haneke’s similarly masterful The White Ribbon, in which Friedel also appears.

Rudolf is prone to staring into the distance, thinking his inscrutable thoughts, perhaps of advancement and approval, perhaps of more efficient methods of extermination. We get a glimpse into his inner life when he speaks with Hedwig on the phone after a party celebrating his promotion to lead an operation that will send hundreds of thousands of Jews to be killed at Auschwitz. His only thought, he tells her, was how best to gas everyone in the room, a logistical difficulty due to the height of the ceiling. This is not, of course, any indication of resentment or animosity toward his fellow officers or anyone else attending the party; just a bored fellow at an office party thinking about his life’s work.

There is a hint of what humanity may be left in Rudolf in the final scene, when he is leaving the party and suddenly begins to dry-heave, unable to vomit but convulsing with either self-disgust at the atrocities he has perpetrated and will continue to perpetrate, or symptoms of some undiagnosed illness from his close proximity to the death camps; maybe it is both. It is a moment inspired by the unforgettable final scene of the great documentary The Act of Killing, in which real-life mass killer Anwar Congo has a similar reaction in the midst of recounting his own crimes against humanity. Glazer accentuates the idea that Höss is reckoning with his own past and future atrocities by cutting to footage of a modern-day cleaning crew preparing the historic Auschwitz grounds for the day’s visitors, then back to Höss as he makes his descent into darkness for all time.

This movie took about ten years to make, and it shows. The attention to detail in both conception and execution is astonishing. In these thousand-plus words, I haven’t even touched on the young Polish girl who hides fruit in the work camps for the prisoners by night, at great risk to herself and her family, and who rescues the music composed within the prison camp, which is also preserved in a beautiful, extraordinary scene, or so many other moments of humanity and horror in this wonderful, devastating film. It is a towering, undeniable work of art. I only hope I can get it out of my head sometime in the near future.

Heil Hitler, et cetera.

Leave a Reply