Is it possible to be both beautiful and dull? Striking, yet on the whole, a complete waste of time? Every chick who’s ever posed naked for money aside, several films come to mind that manage to tease the viewer with engaging visuals and inspired technique, yet utterly fail on the most important level of all the simple craft of storytelling. Consider Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, for example; arguably one of film history’s finest achievements in cinematography, yet so hollow and lacking in depth that the people on screen seem to vanish without any real cause for concern. Perhaps Malick’s intent was dwarf humanity with the sheer immensity of the natural world, but any cinephile worth his solitary Saturday nights remembers first and foremost the men and women of the silver screen ” what they might have said or did ” rather than landscapes or inert objects.

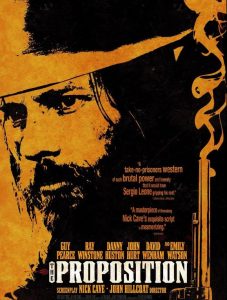

Visual mastery can, of course, leave a lasting impression, but our memories are of character; Rick and Ilsa, Scarlett, Stanley, or the Corleones. So, whenever I come upon a film like the John Hillcoat/Nick Cave creation The Proposition, I am inspired by the talent behind the lens (this is one of the most visually stunning films in years), but left bereft by the refusal to provide us with anything else of value. My eye received the grand tour, but my mind suffered.

The Western can often be a minefield of cliche and predictability, but when it’s clicking (or subject to reinvention), it has the potential to be a lasting work of art. And by taking place in the Australian Outback  a largely uninhabitable wasteland of dust and death  The Proposition had me excited about the genre for the first time since Unforgiven. After all, Australia’s troubled history with the Aborigine is, in many ways, similar to our own shameful legacy regarding the American Indian. In both cases, fear and ignorance gave way to an attempt at reconciliation, only to retreat once again to callous indifference.

The Proposition plays it safe in that it harkens back to the 1880s for its (albeit) limited exploration, but how often has Hollywood ventured into the lives of contemporary Native Americans? So, at the very least, I had hoped for some insight into the dilemma all conquering peoples face when they “tame” a frontier at the expense of another’s traditions and culture. Admittedly, this is best accomplished not by heavy-handed dialogue and overt expressions of guilt (We done’ wrong, Joe….and we’ll pay for it), but rather through sly metaphor and symbolism; much in the way that a Western like Little Big Man could stand in for Vietnam. Not overly familiar with Australian history, I saw The Proposition as a possible joint venture between the sweep of John Ford and the ruminations of Sam Peckinpah  the welcome collision of myth and masculinity.

Alas, The Proposition pounds our skulls with the freakishly familiar tale of family loyalty and revenge; all set to stylized shots and Nick Cave’s often bizarre musical compositions. Again, everything about the technique bordered on brilliant  this kid Hillcoat has a future, that’s for certain  but I wasn’t invited into this world for a single moment. As such, it remains much as a painting behind glass. A vicious, unfeeling intensity prevailed; and while I am always enthusiastic regarding brutal violence, it helps to know a thing or two about the heads being splattered on the desert floor. I’ve read a few reviews that criticized the lack of sympathetic figures, but that was one of the few things I liked about the screenplay.

Maniacal pricks rule the kingdoms of our own world, so why not dominate the fictional realm as well? To a man, these people were bastards and scoundrels, yet I never knew why they carved flesh or left victims writhing in the muck. A great crime appears to have been committed, a brother captured and subjected to beatings by what passed for “the law” in the region, and the remaining brothers commanded by the bonds of blood to bring him back, but that’s hardly enough to justify all the fuss. Charlie Burns (Guy Pearce) has a few minor shades as a man torn between the demands of the Captain Stanley (Ray Winstone) and his vile kinfolk, Arthur (Danny Huston), but only if we pretend not to know that in the end, the brother must be vanquished in order for the past to be left behind. Progress, at least in the movies, always seems to involve murdering a family member, when in reality, it means little more than getting that inheritance a wee bit earlier.

Perhaps it’s telling that many reviews have also alluded to the prose of novelist Cormac McCarthy, a tough, muscular writer who, according to such luminaries as Harold Bloom, is responsible for some of finest literature in the English language. Blood Meridian, one such work I attempted to read, was packed with atmosphere much as this film but seemed to have been written with an especially drunken Hemingway leering over his shoulder. Sentences pulled themselves along, much as a crippled, dying horse hoping to rot away in the shade, and so lacked spark and flourish that I felt kicked in the teeth without so much as a half-hearted apology. Again, I appreciated that McCarthy’s Judge Holden ” a child rapist and heinous Indian killer” was a representation of the American past and dubious moral legacy, but the words themselves never pulled me in. Clearly, though, the book’s reputation renders me a lone, dissenting wolf, but remember, some people also think that Toni Morrison bleeds literary gold, instead of the pompous, self-righteous twaddle she actually produces.

John Hurt (as bounty hunter Jellon Lamb) also shines in an overwrought performance (made-up to look like a deflated raisin that’s been in the sun for several months), and along with his rambling dialogue about Charles Darwin, treats us to a great movie death, whereby Arthur plunges a giant knife into his chest (producing blood-curdling screams) before Charlie sends a bullet into his brain. There are other such delightful dispatches, of course, including an Aborigine who has most of his head obliterated into the mist.

The young, tender Mike (Richard Wilson) receives a prolonged, monstrous whipping in front of an approving crowd, which leads to a great image the wringing of the blood and skin from the lash. Faces are bloodied, flesh is torn and abused, and bodies litter the unforgiving landscape, much as they would in humanity’s last stand. And yet, this film never achieves the grand, overarching purpose it so obviously desires, and remains instead a narrow, isolated story of its time. Where it needs purpose and perspective, it comes across as no more than what we see before us, which, despite its artistic flair, is decidedly ordinary.