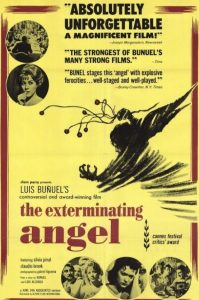

Luis Bunuel was obsessed with ritual and fetish, but he managed to harness them for his art; perhaps selecting embrace rather than denial is what saved him from self-destruction. Social conventions are part of the learned behaviors that members of a society use to relate to one another, but they can also become a languid vernacular that can insulate and destroy. The upper classes, given the distance from reality that wealth can provide, are particularly at risk. Bunuel was no class warrior, in that every social group is quite capable of the same degrees of casual brutality and apathy. In The Exterminating Angel, it is the idle rich, and the formalities with which they cloak themselves, that are given an examination in the most lighthearted black comedy imaginable. This is no harmless exercise, as the outcome is no less than gleeful anarchy and the burning of all a civilized society holds dear.

The surrealist mise en scene is set at a dinner party at which the guests dine heartily, and never leave, the mirror image of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. The guests arrive twice, shot from two slightly angles, just enough to provide some cognitive dissonance and establish two things: one, the guests are definitely here, and two, you are being fucked with. They are of the Spanish aristocracy, for whom Bunuel cultivated a healthy contempt. And for good reason. Brimming with hypocrisy, moral depravity, ignorance, and faux-genteelism would not necessarily land you on this director’s shit list. Failure to recognize these elements in yourself, however, would. Wealth is not nearly as despicable as the self-indulgence that it seems to nurture.

These are the people who took issue with his masterpiece Viridiana the year before. They are poor conversationalists, rude and boorish (ignoring a speech by the host), and bored with satisfaction. Stupidity and vapidity are their chosen languages: ÂThe lower classes are less sensitive to pain. Have you ever seen a wounded bull? Not a trace of emotion. They speak only in scandals, such as the pair regarding a woman rumored to be a virgin as depraved for her virginity. Considering the adherence of Spain to Catholicism, this is a playful punch to the balls. That and one guest’s comment that the Fatherland is in the process of dying, bleeding its rivers into the terminal sea. Though a middle finger to Spain would have served the same purpose, it would have been nowhere near as artful.

Evil portents rule the evening. The staff evacuates just before the dinner begins, and despite the threat of firings, they cannot leave fast enough. The only help who remains is an obsequious waiter who appears to identify with the bourgeois guests more than the staff who has run for their lives. The hostess sends a bear and the sheep out to the garden rather than doing… something… with the guests. A death is predicted amongst the dinner party. A dead chicken, stuffed in a purse, pokes out during a piano recital. Surrealist elements, but together they suggest that the night will end in tears. As the evening wears on, everyone looks to the door, but decorum inhibits their ability to leave, and inhibits the hosts’ willingness to insist they leave. In the end, everyone gets comfortable, doffs their jackets, and stays, perhaps out of a herd mentality.

Now the stage is set for things to get weird, but always rooted in people’s attachment to ritual and expectation. The guests awaken, remaining in the parlor as the waiter serves them breakfast. They cannot, however, leave. Whether the inertia of a large group has firmly stuck everyone in place, or the lack of servants have left them unable to figure out the way to the door, the group must remain in the parlor. A crowd gathers outside the house, but they are unable to enter and break the spell that has taken the house. “It seems unreal… or perhaps too normal.” With time and dwindling resources, the guests quickly shed the trappings of society in their descent into a mob. Throughout the exercise, Bunuel offers little in the way of explanation, leaving it to the viewer to project their own thoughts and fears upon the film. Such is the enduring allure of surrealism.

Part of the joke is the speed with which the guests are at each others’ throats. Despair becomes so pervasive that guests commit suicide, dead bodies are concealed in the hall closet, and drugs meant to alleviate cancer pain are consumed with haste by the other guests. Two lovers commit suicide, and the mob jostles for a look, laughing as the blood runs in rivulets on the carpet. Eventually the impulse to murder explodes as their collective dignity is easily shed in favor of ignorant anarchy. During this time, nobody makes an effort to leave the room. Perhaps this is a comment on the herd’s inability to initiate action, or a tendency to subdue individualism. Potential solutions are considered, and quickly rejected as a fight is generally preferred to cooperation. There is no lead actor or actress in The Exterminating Angel, as the characters are meant to evoke a society, and as such they resemble types rather than discrete individuals.

The symbolism is rich and subject to a riot of interpretation. A disembodied hand crosses the floor to attack a woman delirious with fever. The malevolence of human nature, a rape subtext in a misanthropic scene; insert your own view here. The bear has the run of the house while the visitors cower in the lounge – the proletariat has finally run amok, or maybe the reactionary government of Franco is being portrayed as helpless against the movement of socialism. The metaphors flow past in a surging river, and rarely is it this fun to be swept up. Against the force that holds them in place there are incantations, pagan rites, prayer, superstitious Kabbalah babbling, Masonic pleas for help, and the reason of science.

None of them are able to break them of their torpor. It is as if nothing can supersede the trappings of society and the customs that give us comfort. In the end, as the guests lose their grip on reality, they realize their absolute dependence on ritual is what enslaved them, and so it can set them free. Though by repeating an earlier moment from the night they are able to leave the house, this is really a sarcastic poke to the ribs by the director. Only by burying themselves deeper in the formalities that hold them in thrall can they continue their usual repetitive lives.

The survivors gather in that place which exalts mindless ritual above all other worldly actions – the Church. And in so doing, they are placed under a similar yoke. It is telling that in the final shot, a column of sheep make their way into the Church, an exceedingly sly comment upon anyone who follows the same path. The summation makes it clear that the ceremony that sets us in our pleasant complacency is what ultimately will destroy our civilization. Rigid social structures and an apathetic contempt for knowledge that does not bring in the bacon has made us extraordinarily dumb despite ready access to information. We are but a shortage of a key resource away from bludgeoning our neighbors in frolicsome abandon. Human nature is mercurial, but can be redeemed by the pursuit of wisdom and understanding – things we do not require to survive, but things that are essential to our dignity and peace.

It would seem that such a ridiculous plot and increasingly distorted characters would be so distanced from our sensibilities that we would feel no empathy for them, nor any sense that we would quite easily fill their shoes in a roughly similar situation. Part of the magic of a surreal and often abstract work is that you are sucked in despite yourself, silently claiming that we would not follow such an example while realizing we do this to each other on a daily basis. Though such a film would place any ordinary director among giants, Bunuel would go on to create additional masterpieces, his talent seeming to hit an exponential growth curve in the 1970s. His films are timeless and remain fresh no matter how many times you have seen them, and are red meat for the intellectual who looks to cinema as a continually evolving art form.