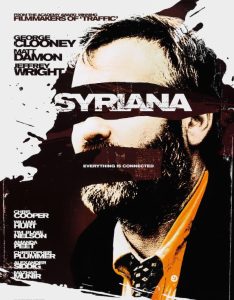

Written and Directed by Stephen Gaghan

Starring:

– Kayvan Novak as Arash

– George Clooney as Bob Barnes

– Amr Waked as Mohammed Sheik Agiza

– Christopher Plummer as Dean Whiting

– Jeffrey Wright as Bennett Holiday

– Chris Cooper as Jimmy Pope

Why on earth do I continue to see movies like Syriana? Why, when there are so many opportunities in this big, wide wonderful world to skip through the park, work with children, or take puppies on walks while the sky glistens with morning dew and rainbows, must I be drawn to motion pictures that leave me drained, battered, depressed, and cursing the darkness? I’d have it no other way, of course, for sentimentality and mindless escape are as foreign to me as compliments in bed or lucrative job offers, but I often wonder what it might be like to have no concern whatsoever for life’s bitter truths. And yet, despite Syriana’s obliteration of hope, its unapologetic immersion in the brutality of our times, and the refusal to offer even a mere glimmer of hope as we continue our long march to the collective graveyard of dreams deferred and dashed, I was as captivated as a young child at the circus. My glee was that of a cackling demon upon receiving the first cart of damned souls, or even a sadistic warden as the hardened cheeks of his charges are led to the showers. It’s a movie for anyone toasting the end of civilization, and while it remains just that — a movie — it never leaves the mind that every scene, every image, every last frame, is not only probable, but likely happening somewhere in the world at this very moment. It’s about crime, corruption, terrorism, and oil, although it’s impossible to distinguish between them at all; as if those chronicling our world have finally been granted permission to speak openly about the way the world has worked for centuries on end. Only now, we do in fact possess the means with which to destroy ourselves.

Syriana, like Traffic (also written by Stephen Gaghan), is a jumbled, complex, and exhilarating work; a film that throws out mere pieces of narrative, always trusting the audience to wait patiently for connections that may or may not come. The camera itself is unsteady, as if the only way to portray two hours of globetrotting and political intrigue is to keep us breathless and just a little dizzy. There are literally dozens of faces to remember, although a few do manage to establish a primacy of sorts. Still, this is not about any one man or woman, as the nasty business of oil could hardly be reduced to a single relationship or chain. Far from a shadowy cabal, the corporations and key figures operate largely in the open, couching their transactions in terminology so benign that it requires little effort to see it as “just business.” Many of us have little affection for Big Oil, of course, as we bitch about gas prices, wag our fingers at President Bush and his cronies, or question the motivations behind the invasion of Iraq, but almost in the same breath as our complaints, we draw the line at any real regulation or accountability. We too want it all when it comes to our energy, and whatever needs to be done to maintain a cheap, seemingly unlimited supply, we’ve already signed the deal. Surely, though, if it gets too sticky, we’d rather you close the door and leave us out of it. The harsh light of reality tends to make that drive across town to the Outback Steakhouse in our Hummer a little less jovial.

What I like most about Syriana is that it refuses to hide its political leanings or propagandistic identity, choosing instead to have a well-defined point of view. When so much of life is managed, controlled, and studied to ensure maximum participation (and minimum offensiveness), it is quite refreshing to find a film that makes you take a stand. While neither the script nor the director resort to heavy-handedness or oversimplification, it is impossible to remain unmoved in the presence of so vivid a portrait. Yes, the film posits the belief that the American government, through its intelligence agencies, monitors the global network to ensure favorable elections, governments, and economic developments, but as obvious as that idea might be, there remains enough historical ambiguity to allow for a spirited debate. At the very least, indifference is and must remain the refuge of the unconscious. Fictional companies and leaders are put forth in the film, but after Iran, Guatemala, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chile, East Timor, and Iraq, does anyone doubt the disturbing legacy of our nation? Sure, in many ways this could be an American tale, but it is impossible to see how anyone of good conscience could ever step forward to cease operations. Insert a Democrat, or an Egyptian, or even a hero from a Frank Capra movie, and very little would change. Perhaps that’s why we are routinely supplied the illusion of elections to fight over like so many scraps of cheese before starving rats. In the end, they’re all beholden to the same god.

Among the story threads are Bob’s tale, and as played by a meatier George Clooney, he is a covert agent who isn’t above killing for king and country, but he’s the last man to abide betrayal. He acquires a conscience of sorts near the film’s conclusion, but it is telling that he is killed for the effort. What’s more, his actions, had they been successful, would have changed nothing, as the forces of reaction are extremely patient, after all. Bob has a family (in name only), though his wife and son live in Pakistan, where she is forced to live as a “secretary.” In only a few brief snippets, we understand that a man like Bob is incapable of a meaningful relationship, and we instantly wonder how on earth undercover officers maintain their sanity as they attempt to live “normally.” He is assigned to “remove” a key roadblock to peace in the Middle East, although as in our own world, we see that peace is far from the absence of tension, but rather the presence of favorable economic conditions. Bob never appears to be anything other than a jaded company man, and thankfully he is not sacked with a dull subplot involving a love interest. And we know that such a movie could easily exist — just picture Julia Roberts as the ingenue.

Matt Damon is also on board as an energy trader (named Bryan Woodman), a title which is never fully explained, albeit deliberately. There are thousands of such men wandering the globe in search of the big prize, and I doubt any one of them could describe their job in less than an hour. Bryan and his family live in Switzerland, although at a moment’s notice, he’ll be asked to Spain to sweet-talk a young prince. Bryan, while the only character saddled with an intact family, is far from domesticated, as the only real time he spends with his brood ends in tragedy. Other than that, he is in Iran, Saudi Arabia, or any number of key points on the energy grid. The strength of this tale lies in the ease by which Bryan turns on the “role” of business executive. We all know that the life of a high stakes money man is a gigantic fraud full of handshakes, glasses of brandy in hotel rooms, and casual chats in limos, but its representation never ceases to reduce me to a pool of disgust. Perhaps moral clarity ensues when paychecks leap into seven figures, but one glance at this life reminds me of why my ambitions remain little more than having a little cash at the end of the week to hit the movie theater. Flying under the radar may not produce a house in the country, but at least you can retain your dignity. I know, that’s nothing more than dressed-up bullshit disguised as nobility, so who’s fooling who? Hell, I know damn well that I’d have half my family shot for a nicer apartment.

And then there’s Jeffrey Wright as Bennett Holiday, a high-powered attorney who works hand-in-glove with various oil men, only to realize that even small pangs of conscience are quickly extinguished by the realities of the marketplace. Investigators, in need of a sacrificial lamb to satisfy certain P.R. obligations, are calling for more meat than the corporation is willing to give, leading Bennett to help broker a deal. In the midst of this we meet Dean Whiting (Christopher Plummer), Jimmy Pope (Chris Cooper), and Danny Dalton (Tim Blake Nelson), whose brief monologue on corruption is so tightly worded and depressingly accurate that we all but throw up our hands, mutter hopelessly, and arrange a long-awaited interview with the dull end of a switchblade. For no matter how much we might be appalled by the sheer avarice of these professional liars, there are millions more waiting in the wings. Sure, consumers receive benefits from all this wheeling and dealing, but shouldn’t it make a difference that what we get out of the bargain is the very last thing on the priority list? Oh, sorry, that would be working conditions, benefits, and gross pay for the suckers at the ass-end of things. Sure, I understand the world and no, I don’t expect to snap my fingers and produce a workers’ paradise where everyone shares and loves and cuddles with joy, but must all roads lead to power and profit? You don’t need to tell me the answer.

In the end, this is a sweeping epic about where we are now, and it’s so much the better for not cleaning itself up. Bryan returns to his wife at the end and another man seems to feel bad for actions taken, but a story such as this is impossible to resolve. The day after the story ends, the same men will be back at work; the same disillusioned young Muslims will be recruited for terrorist acts; and the same U.S. government will be laying its cock on the table while trying to convince the rest of us that it’s actually a heart on a sleeve. And speaking of the terrorist angle, it must be praised for its subtle turn, although the end result is far from a surprise. What grinds away at the audience is the realization that, in fact, poverty and despair are the proud parents of martyrdom, and so long as exploitation and inequality reign as champions of the global economy, buses will continue to explode and city life remain one of high alert. And consider the words of the young prince bent towards reform, yet utterly baffled by the United States’ shocking display of insecurity: “Five percent of the population, yet fifty percent of overall defense spending…..someone now realizes how ineffective they are at communicating with the world.”