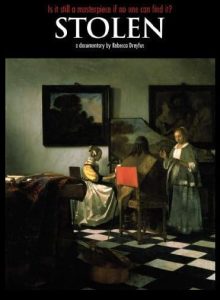

Directed by Rebecca Dreyfus

Goddamned Irish. When the drunken sons-a-bitches aren’t stinking up assorted bars, pubs, and city streets, they’re fixing elections, irritating the uninformed with endless tales of woe, and speaking so romantically of the mother country that one can’t help but wish the fuckers had been wiped out by a series of potato famines. And if their legacy of corruption, greed, and angry Catholicism weren’t enough to inspire murderous rage, I find out that most likely — and the evidence is strong, if circumstantial — the Irish Republican Army, combined with notorious Irish gangsters like Whitey Bulger, were behind the March 1990 burglary at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston; a heinous crime that removed several masterpieces of art from public view, including Vermeer’s “The Concert,” Rembrandt’s “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” and several works by Degas.

After all, it was not a crime of passion (few art thefts are about an appreciation for the paintings themselves), or even ransom (the criminals made no attempt to contact the authorities), but simply an exercise of power. Usually, these paintings are swapped around the underground, often traded for drugs, but just as often used to flex a bit of muscle among thieves. And as several paintings were cut right from the frames, this was a job with no respect whatsoever for the inherent value of art, as if anyone would suspect the Irish of being able to appreciate anything that didn’t immediately convert to a back alley stupor. Although no one has been arrested for the crime, it is strikingly similar to other thefts involving elements of the IRA, and this is Boston after all — a city rivaling New Orleans for its (lack of) adherence to justice and fair play. The Mick bastards.

Rebecca Dreyfus’ fascinating, enraging documentary is surely to be one of the best of the year, as it combines the best elements of a crime novel with a genuine attempt to place these works of art in their proper context. We also learn quite a bit about Ms. Gardner herself through letters and flashbacks, all voiced by Blythe Danner. Apparently, Gardner was quite the free spirit in her day, and seeking controversy wherever she could find it, she lived as few women of the late 19th century could, although her vast fortune helped a great deal. Her travels to — and love affair with — Italy brought about a need to collect fine paintings for her collection, though instead of locking such masterpieces away for their mere value alone, she sought to establish a museum in the style of great Italian architecture.

Her desire was that the world would forever view great art in a contemplative setting. Even today, those who work to preserve Gardner’s vision are obsessively devoted, including one man in particular who claims to have been “spoken to” by a portrait of the woman herself when he was but a lad. As a ward of the state, the boy felt comforted by the motherly image, and it stands to reason that he later worked for her glorification. Interviews in the film reveal an eccentric, teary-eyed soul, who just happens to wear mascara. Still, he hopes to have the paintings returned, if only to make him feel whole again.

The center of the film, though, is the gentleman investigator Harold Smith, an odd duck of a man who wears a bowler and an eye patch, and just happens to suffer from a skin cancer so severe that he appears to be melting away before our eyes. Even his nose is completely rebuilt, and while his appearance is shocking, we see that above all, he cares deeply for the art itself. He, like many others interviewed throughout the film, believe that only by standing in the presence of these works can we truly understand our humanity. Mere pictures or facsimiles are not enough.

Smith flies across the country chasing leads (usually the ravings of liars and fools), and even ventures to England to speak with a former Scotland Yard detective who has particularly depressing news about the IRA link. We might not get a full biographical sketch of Smith (though we do learn that his cancer stems from an exposure to harmful rays as a young man while being treated for a skin condition – and yes, the experiments were at the behest of the U.S. military), but it’s enough that he’s always present as a doggedly earnest advocate. He’ll go where he’s called, even if we can sense that it just might be a fruitless chase.

Still, as we learn from the postscript, he worked tirelessly until a week before he died, a victim at last of a fifty-year cancer battle. We’re not sure who will take up the cause from Smith (the film doesn’t say), but unfortunately, there’s little cause for optimism. After all, it’s been sixteen years and not one clue leads in any particular direction. Instead, we’re left with possibilities, guesses, and stabs in the dark.

Still, one pointed question hangs in the air long after the film has ended — what is more important, the recovery of the art, or a successful prosecution of the thieves? In other words, if it were possible to return the paintings to their proper home and let the guilty men go free, would it be wise to do so? Needless to say, the FBI would be more than satisfied rounding up the perpetrators even if by doing so, the art went up in flames with the gangsters’ hideout. As g-men, they care little for beauty or its appreciation; they only want to see law-breakers behind bars. In this case, though, the voices of the art world speak most reasonably in defense of simple recovery, even if the criminals were in fact rewarded for their deed. Should ransoms be paid, if one day they were sought?

A $5 million reward has been established, and since the crime on St. Patrick’s Day 1990, not one person has tried to collect the sum. There are a few self-important ex-cons in the mix who toy with Mr. Smith and the authorities, but the film doubts their truthfulness in the matter. After all, if they had key knowledge, why did they wait so long to come forward? And why would they ask for money up front unless they had other, more sinister motives? The most bizarre fellow of all, though, is some Brit nicknamed “The Turbocharger.” He has ties to the underworld of art theft, but he’s such a character that it’s impossible to distinguish between hard evidence and simple self-promotion. The latter seems likely.

By combining mystery, drama, biography, and a love of art, the documentary succeeds wonderfully, and simultaneously depresses the hell out of us. Combine this unsolved case with the recent theft of Munch’s “The Scream” from an Oslo, Norway museum, and you have a troubling trend that never seems to go away. Art, regardless of its price or perceived value, really has no meaning unless it can be discussed, debated, and poured over with respect and care.

The auction houses and record sales make the headlines, but after hearing critics and experts discuss “The Concert” for but a few moments, it reminds us that at any level, these works are for the world to interpret and re-interpret again and again. As such, there is no firm conclusion about a single one of them, and all viewers bring their own experiences to the table. And here we had numerous works in an accessible location for our appreciation and awe. Stupidly, selfishly, monsters of the highest order have denied us the further pleasure of basking in their genius, and if we ever get them back, their unfortunate condition may warrant their infuriating destruction. Art theft, then, in its current incarnation, is arguably the most incomprehensible of crimes, as it seems utterly without motive or desire for financial reward. Because it’s so mindless and exasperating, I continue to follow the Irish connection, cold trail be damned. Perhaps one day, they’ll taste the ever-tightening rope of justice.