Ted Bundy would have to be one of my favorite serial killers. How can you not love the endlessly fascinating little scamp, given his yen for necrophilia and keeping severed heads as trinkets? Indeed, his final killing rampage at a Tallahassee sorority house, in which he shape-shifted into some kind of amped-up, sexually insane fox in a chicken coop, suggests a volcanic level of fury that few of us can even imagine, let alone act upon.

Where on Earth does such pitch-black, sadistic hatred spring from?

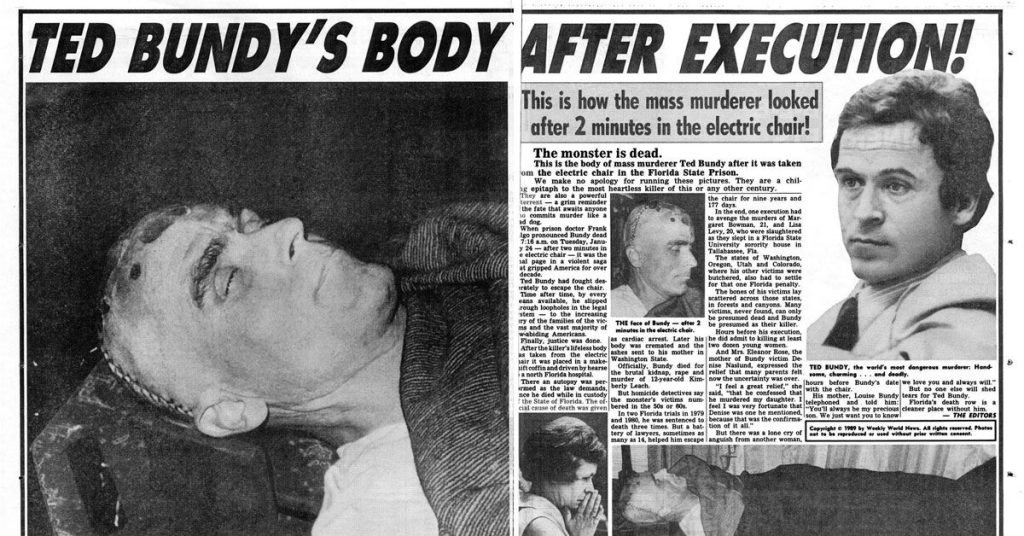

Others of his ilk can at least point to ‘excuses’, such as bad genes, an abusive upbringing, rampant bullying, drug abuse, head injury or insanity. Ted, however, simply chose his career of evil, wading clear-sighted through the blood and gore with ice in his veins. This was a man with a fanatical need to overpower and control, even after death had mercifully released a victim. By the time he was strapped into Old Sparky in January 1989 there were no regrets, no remorse, no qualms and certainly no apologies. An artist of sorts, he dedicated himself to lethal self-expression, a steely pursuit that has no doubt bestowed immortality. Just look at how many books, films, songs and TV shows have already been made about his awfully naughty exploits.

In short, if you believe in capital punishment, there’s no better candidate for its practice than Mr. Theodore Robert Bundy. The man was sane, racked up a substantial kill count and couldn’t have been guiltier (e.g. incriminating teeth marks were found on a 12-year-old girl’s buttocks). There’s no doubt he was one of the most appalling pieces of excrement that ever besmirched the face of our planet. Not only that, but he was a Republican campaigner. Only a fool would lament Bundy’s zapping, yet I’m not a fan of capital punishment.

Why?

Well, please don’t think of me as a liberal, some kind of namby-pamby progressive that values the rights of criminals over victims. I believe in punishment and no matter what the rabble-rousing tabloids try to tell us about prisons being little more than three-star hotels there’s something horrifying about a decades-long incarceration where you can’t even enjoy a private shit. It’s just when it comes to the death penalty (and excepting the ever-present threat of a miscarriage of justice) I find it a tad contradictory for a government to insist it’s wrong to kill your fellow citizens and then do just that themselves. We’re gonna show killing is wrong by… killing is one helluva weird message to send.

I also think it’s better to imprison rather than flush pieces of shit like Bundy because every moment they remain cooped up behind bars it demonstrates we’re better. After all, as soon as a noose is slipped around a throat, we start to move a little closer to what we supposedly abhor. Saying that, I have little doubt that if a referendum were held on capital punishment in a place like Britain most people would vote in favor.

Anyhow, I might be against it, but I’m all for it on the big screen. From Jesus’ gory crucifixion in The Passion of the Christ to Horace Pinker’s wisecracking electrocution in Shocker, cinema has a long tradition of sinking its celluloid teeth into this juiciest of subjects.

The executioner: Albert Pierrepoint in Pierrepoint (2005)

Compartmentalisation is a mental process in which a person separates acts. For want of a better phrase, it’s essentially a coping strategy, a useful approach to take when you’re engaged in heinous behavior and not utterly insane. Serial killers often employ it and as the masterly biopic Pierrepoint suggests, executioners may well, too.

The real-life Albert Pierrepoint came from a family of hangmen, his two-decade plus career encompassing a fascinating period in British criminal history. Between 1932 and 1956 he executed Nazi war criminals, two wrongly convicted men, an acquaintance, a handful of serial killers and Britain’s last condemned woman. No one seems to know the exact number, but conservative estimates put his final haul at more than five hundred.

Gulp.

As played by the marvelous Timothy Spall, Pierrepoint is a jowly, studious man that takes the job deadly seriously from the moment he’s appointed. His mother can’t understand his decision, though. Why do it? she asks. “It’s just in me,” he replies. “I always knew it would come out some day.” And soon nothing’s really the same, no matter how hard he tries to remain professional and detached. Folks both inside and outside the prison like to dwell on the murderer’s actions but not Pierrepoint. “I never concern myself with what they’ve done,” he says. “It doesn’t matter to me.”

Instead, he sees an impending hanging as an exercise in efficiency in which a clean kill is ensured by matching a man’s height, weight and physical condition with the length of the drop. Pierrepoint appears to remove all emotion, even when directly insulted by an imminent victim. He adopts a combined approach of disorientation and speed to ensure a successful execution, enabling him to go about the job in a clinical manner. Yes, he takes pride in how quickly he can complete the process (less than eight seconds is his record) but remains dispassionate while separating that second and third vertebrate as neatly as possible. Afterwards he treats the ‘innocent’ body with respect and compassion, obviously believing in atonement.

But as Pierrepoint unfolds, it’s clear he needs more than one defense mechanism to deflect the horror and keep his moral code intact. And so just like a serial killer, he compartmentalizes. “When I walk into that cell,” he tells an assistant, “I leave Albert Pierrepoint outside. I never mix the two.” And if any cracks appear, he insists the blame lies with other parties. “It’s the government that wants these people executed,” he adds. “That’s the way I see it.”

The most interesting period in Pierrepoint’s career arrives during World War Two’s aftermath. Called in by the top army brass to dispatch ‘firm but fair’ justice to a plethora of Nazis like Josef Kramer and Irma Grese, we start to see some worrying parallels between these seasoned murderers and our main man. Beforehand Pierrepoint only executed one person at a time; now he’s expected to slog through thirteen a day. Suddenly he’s up to his neck in the business of mass slaughter. Even an experienced soldier called in to help Pierrepoint is unsettled by the relentless procession of death. “Standing with them on the gallows… both knowing what’s going to happen,” he says. “I think it’s the knowing that’s the worst part of it.”

Worryingly, Pierrepoint justifies his lethal behavior in much the same way as the Nazis, in that he’s essentially following orders. “You do your job,” he tells an assistant “and I do mine. And I shall sleep soundly.” Is it even remotely fair to compare Pierrepoint with someone like Kramer, the so-called Beast of Belsen? Both killed with their government’s blessing, one in the name of racial hygiene, one in the name of justice. Yet we’ve already learned from the grainy news footage of Belsen played at the cinema Pierrepoint attends with his increasingly unsettled wife that everything there ‘was done with hideous precision.’ Both wanted to be rid of their victims as quickly as possible.

Throughout it all, Pierrepoint shuns publicity. He dislikes anyone knowing his trade and has a tangible sense of integrity, but his unavoidably prominent role in the numerous Nazi executions is lapped up by the newspapers. This initially results in public support, but things start to change with some contentious post-war executions and the growing influence of abolitionists (who are happy to call him a murderer). Even the odd customer in the pub he’s started running insists his hands are ‘filthy with blood’. Such a state of affairs is bound to have an effect. “I’ve got things in here,” he tells a mate, tapping his forehead, “that I’d rather weren’t there. I can keep them at bay, but they’re waiting for me. Waiting for me to let my guard down. Waiting all the bloody time, they are.”

Pierrepoint does not have a strong anti-capital punishment vibe. It prefers to concentrate on the effect relentlessly killing people has on one dignified, reserved man. The real-life Pierrepoint issued contradictory statements on whether he was for or against hanging, but his fictional representation (which undoubtedly takes significant liberties with the truth) more than suggests it has corroded his soul. The man tries to be a killing robot but his humanity wins out. Frankly, this is the one misstep in an otherwise superb movie. Ambiguity toward such a disturbing job is always a lot more intriguing.

The murderers: Matthew Poncelet in Dead Man Walking (1995), Perry Smith and Dick Hickock in In Cold Blood (1967), Jacek Lazar in A Short Film About Killing (1988), Barbara Graham in I Want to Live (1958), Cindy Liggett in Last Dance (1996) and Derek Bentley in Let Him Have It (1991)

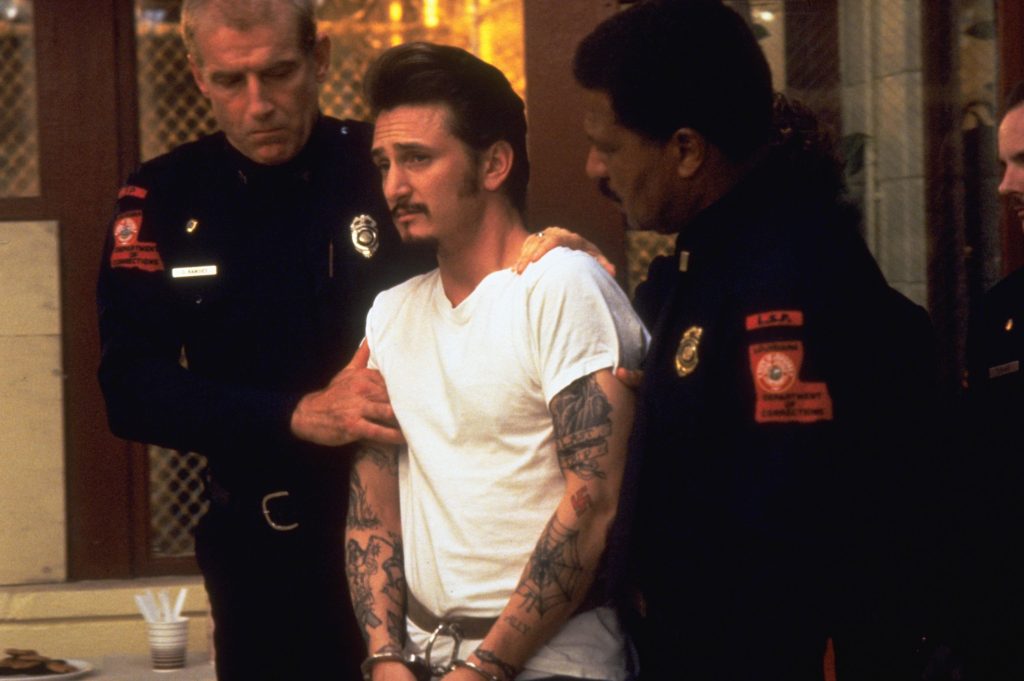

Poncelet is not as bad as Bundy but he’s cut from the same cloth. A murderer, rapist and arch manipulator, at least he has a slight ‘excuse’ in the form of a malign older influence and a disadvantaged childhood (including the premature death of his father). Poncelet is poor white trash, having moldered on death row for the last six years after wiping out a teenage courting couple in the woods. There’s not much more to do than await his showdown with the Grim Reaper, dream of God in a chef’s hat covering him in breadcrumbs, and write to a nun to help him in a last-ditch appeal for clemency. Not that he’s interested in her spiritual guidance or the possibility of having his soul saved. He just wants someone to listen while blaming all and sundry.

Hateful and refusing to admit responsibility, Sean Penn is pitch-perfect as this sullen, self-pitying Hitler fan boy. He reeks of unpleasantness and contempt, but Penn is a savvy enough actor to make sure we get glimpses of the scared little boy hiding beneath the arrogant, swastika-adorned exterior. Of course, one of the great things about the remarkably nuanced and balanced Dead Man is that you can watch it as a pro-capital punishment fanatic and still walk away with your stance intact. Or as one guard, who is part of the execution team, says: “These prisoners get what’s coming to them.” Poncelet is despicable and guilty so what does his final redemption matter? He’s found some maturity in the last twenty minutes of his existence? Big fucking deal.

Ultimately, you have to believe in life after death for his change of heart to mean anything. And if his deliverance is essentially for God’s ears, it prompts a raft of other questions like why did the Almighty allow the murder of two innocents? Wouldn’t it have been better to have turned Poncelet into a nicer person rather than ‘saving’ him through Jesus later? Are the slain teens and Poncelet now going to be friends in heaven? And so on down that particular rabbit hole. The only question that remains for me after the lethal cocktail of drugs has entered his bloodstream is: Has Poncelet’s death made anything better for those that remain down here on Earth?

Religion also plays its lovely part in the aftermath of the 1959 killing of an ordinary Kansas family during the deservedly acclaimed In Cold Blood. Ex-con losers Perry Smith (Robert Blake) and Dick Hickock (Scott Wilson) travel to the Clutter family’s isolated farm after hearing they’ve got ten grand tucked away in a safe, but a night-time raid nets only forty bucks. This disappointment leads to bang-bang time and our savage, incompetent perps facing the gallows.

The prosecutor tells the jury that if Smith and Hickock get life imprisonment, they will be eligible for parole in seven years. “Gentlemen, four of your neighbors were slaughtered like hogs in a pen,” he says. “They did not strike suddenly in the heat of passion, but for money… They who had no pity now ask for yours. If you have tears to shed, weep not for them. Weep for their victims.” He then picks up a bible and quotes Exodus and Genesis to ram home how the prosecution’s lust for lethal vengeance is based on divine approval.

Many proponents like to argue that the death penalty acts as a deterrent but flicks like Dead Man and the grimly realistic Cold Blood show otherwise. Poncelet, Smith and Hickock don’t think about getting caught. Indeed, Hickock thinks the robbery will be a ‘cinch, the perfect score’. Misfits like him focus on the present and the resentful sating of their anti-social needs. Once it’s over, they can’t even comprehend what they’ve done. Listen to Smith: “It doesn’t make sense. I mean, what happened. Or why. It had nothing to do with the Clutters. They never hurt me. They just happened to be there. I thought Mr. Clutter was a very nice gentleman. I thought so right up to the time I cut his throat.” His only concern by the end of his time on death row is to avoid shitting himself when the rope snaps taut.

Smith is against being executed for his callous crime but Hickock believes in capital punishment – in principle. Or as he says: “Hell, hanging’s only getting revenge. What’s wrong with revenge? I’ve been revenging myself all my life. Sure, I’m for hanging. Just so long as I’m the one not being hanged.” When his time comes, he thinks he’s being sent to a ‘better world’.

In common with all these killers, Jacek Lazar in Poland’s A Short Film About Killing is a complete waste of space. He’s a twenty-year-old anti-social drifter who’s just wandered into Communist-era Warsaw. It’s easy to see no good will come from his arrival as he does nothing but scare pigeons, drop a rock on a passing car from a bridge, look sullen, assault a man in a public toilet and end a taxi driver’s life in a messy, prolonged murder. He is immediately caught.

Lazar (Miroslaw Baka) is only slightly humanized after his death sentence is announced. Now we learn he’s haunted by culpability in the accidental death of his beloved twelve-year-old sister. “If she were alive, maybe I’d never have left home,” he tells his lawyer. “Maybe I’d have stayed.” Lazar, however, expresses no remorse for the murder he committed before the prison guards frogmarch him to the hangman.

Killing makes the documentary-like execution feel like a tit for tat sequence, its title suggesting there’s no distinction between the two acts of deadly violence. Indeed, this raw 80-minute flick is an exercise in nihilism, its bleakness intensified by an extensive use of green filters that make the ugly Polish capital look like it’s recovering from a nuclear winter. Fans of capital punishment, however, can point to Lazar’s end (like Poncelet’s) being quicker and much more humane when compared to his victim’s ghastly final moments.

Apart from the witch trials that swept Europe and America from the 15th to the 18th centuries and those good ol’ Islamic stonings, men tend to taste lethal justice much more often than women. This is because they are nastier and more likely to get involved in authority-bothering hijinks, but given the chance women will poison, stab and shoot. Take the ballsy hooker Barbara Graham in I Want to Live!, one of Hollywood’s first anti-capital punishment flicks. She’s accused (along with two accomplices) of murdering a crippled, elderly widow during a robbery, but police dirty tricks and relentless publicity about ‘Bloody Babs’ ensure there can be only one verdict.

“I wanna thank the gentlemen of the press,” she tells a conference after she’s sentenced to die in San Quentin’s gas chamber, surely one of the last century’s cruelest methods of execution. “You chewed me up in your headlines and all the jury had to do was spit me out… Are you satisfied now?”

As played by the Oscar-winning Susan Hayward (in a performance all over the place), Live! has an awkwardly written first half and other faults, including an ill-fitting, energetic jazz score. However, it’s good at depicting the mental torment of knowing the end is in sight. “I feel like someone is pulling out my guts with their bare hands,” Graham cries at one point. Often feeling like a forerunner to Dead Man Walking during the build-up to its tense finale, it doesn’t shy away from the ugly details, such as the preparations with sulphuric acid and the vulture-like newspaper reporters almost pressing their faces against the windowed chamber. “When you hear the pellets drop, take a deep breath,” Graham is told by a guard while being strapped into the chair. “It’s easier that way.” Ever sassy, she simply replies: “How do you know?”

Almost four decades later Sharon Stone also played a condemned murderer in the pedestrian, uninvolving Last Dance. Whereas Live! wisely didn’t include any flashbacks of Graham’s crime leaving us with a degree of doubt about her involvement, Dance shows Cindy Liggett (Stone) high on crack breaking into a house at night to smash the shit out of two high school kids with a tyre iron. Supposedly anti-capital punishment, it’s easy for an advocate to watch this box-office dud and declare Liggett deserves everything she gets. And just like the vastly superior Dead Man, it’s baffling to watch a concerned party (her lawyer) weep bucket loads of tears over the demise of a guilty-as-hell double murderer because she’s now a ‘changed’ person and has learned to draw while behind bars. Similarly, her lethal injection exit (depicted by her fluttering eyelids) seems like an awfully dignified way to go.

Abolitionists tend to be on firmer ground when bleating about miscarriages of justice. In America scores of death row inmates have been exonerated in the last half century, offering cast-iron proof that making the naughtiest of criminals go bye-bye is not really a sound idea. In Britain there were two high-profile, post-war cases that resulted in the country doing away with capital punishment in the mid-60s. The first was partly covered in 1971’s superbly creepy 10 Rillington Place (in which a retarded Welshman was hanged for a serial killer’s crimes) while the second was 1991’s Let Him Have It.

Derek Bentley (Christopher Eccleston) is a good-natured kid who comes from a caring family. Unfortunately, he’s also illiterate, sub-normal and epileptic, making him easy prey for the sixteen-year-old Christopher Craig (Paul Reynolds), the Bogart-loving, de facto leader of the local scallywags. Craig ropes him into a bungled armed robbery at a London warehouse, leaving one copper wounded and another dead. The nineteen-year-old Bentley is subsequently sentenced to death while the underage Craig gets imprisonment – even though he pulled the trigger. Christ, when your luck is out, it’s really out…

The convincing, well-paced Let Him boasts an excellent recreation of 1950’s Britain, including the easy availability of post-war guns. There’s no doubt it depicts Bentley with the utmost sympathy and you’d have to be a raving nutter to agree with his hanging. However, a woodentop is dead and someone has to pay. Or as the Home Secretary tells the police officer’s grieving mum before a biased judge gets his hands on the case: “Justice will be done.” Forty-five years after he briefly met Albert Pierrepoint in 1953, Bentley’s murder conviction was overturned.

The ghouls: Sister Helen Prejean in Dead Man Walking, Truman Capote in Capote (2005) & General Paul Mireau in Paths of Glory (1957)

By its very nature, the end game of capital punishment is bound to attract the fucked-up. You know, emotional vampires, the deluded and damaged, clairvoyants, crusaders, exploiters, profiteers, publicity-seeking politicians chasing the populist vote by getting tough on crime and, of course, the goddamned religious. Enter Sister Prejean (Susan Sarandon). Nominally our heroine, she would have to be one of the most sickening, insufferable characters in twentieth century cinema. A meddling do-gooder par excellence that spouts some of the most abominable dribble I’ve ever heard (“You are a son of God, Matthew Poncelet… Christ is here… I love you.”)

Her only defense is that she did not set in motion the whole shebang with the loathsome perp. Apart from that, she positions herself in the doorway between life and death trying to offer spiritual counsel to all sides while insisting her creed is the way into the light. Hmm… And who is this person? Surely a vastly experienced individual au fait with the extremities of human emotions? Well, no. She’s a naive, middle class virgin from a comfortable home who once sang for the inmates of a juvenile detention center. Call me a cynic, but contact with Poncelet appears to finally bring some much-needed color and drama into her otherwise sedate, boring life. And boy, does she dig her claws in. For once engaged, this woman’s arrogance, bare-faced absurdity and desire to suck on the marrow of high drama know no bounds.

Asked by a senior priest whether her involvement is down to ‘morbid fascination’ or ‘bleeding heart sympathy’, she can only reply that Poncelet wrote to her. Straightaway her incongruous presence on Death Row is highlighted when a metal detector objects to the silver crucifix adorning her chest. Nothing illustrates her clumsiness better, though, when she goes to the parents’ home of the girl Poncelet murdered only to be chased out when they discover she’s batting for both sides. “How can you sit with that scum?” the father demands. “Poncelet is God’s mistake and you want to hold the poor murderer’s hand? Sister, you’re in waters way over your head. You can’t have it both ways.”

But then why shouldn’t her faith have prompted her to make such a monumental blunder? As Dead Man neatly shows, quotes plucked from the bible can be for or against killing. Trying to make sense of that contradictory tome is always gonna be confusing, but it’s little excuse for this nauseating nun’s irrelevance and leech-like behavior.

She laps up the raw emotion while riding a personal rollercoaster, but in the excellent Capote the renowned writer Truman Capote takes a different tack. He sees the Clutter killings as a chance to make some money and secure his fame by inventing ‘an entirely new kind of writing’. Not to mention develop an icky crush on a caged killer. Weirdly, he often makes the murders about himself, turning events around to blab on about his abilities. Indeed, his hubris is quite something. “The book I’m writing,” he says of the convicted slayer Smith, “will return him to the realm of humanity. It was the book I was always meant to write.”

Yet such an approach doesn’t explain why he hangs around a funeral parlor and lifts up the coffin lids to take a peek at the shotgun-assaulted remains of the Clutters. “It comforts me,” he tells his boyfriend over the phone. “It’s a relief.” And no, I don’t know what that attempted explanation for such macabre behavior means, either. However, Capote’s manner often paints him in a poor light, such as telling the detective in charge of the case upon their first meeting “I don’t care one way or another if you catch whoever did this. I’m writing an article on how the Clutter killings are affecting the town.” Bribery, flattery, lies, manipulation and even exploiting Smith’s aspirin addiction for his motorbike-damaged legs duly follow as he worms his way into the affections of whoever can provide insight.

Capote zeros in on the ‘desperately lonely, frightened’ Smith, offering to get him a ‘proper’ lawyer for an appeal once the death penalty is announced. Perhaps he’s sincere, but more than likely he sees it as a necessary tactic to secure extra time for interviews, especially as Smith won’t talk about the night of the murders. To Smith’s face he insists he’s a friend, but once away from the killer he refers to him as a ‘gold mine’. Capote, who spends little time with the friends and associates of the murdered Clutters, never seems to grasp the monstrous act that Smith and his accomplice carried out. The self-centered, routinely pathetic Capote only sees the stays of execution and protracted legal wrangling in terms of the effect it has on him and the inability to give his book the ending he craves. “It’s torture,” he drunkenly complains. “They’re torturing me.”

But as much as I’d like to take the moral high ground, I’m complicit in the man’s ghoulishness. Capote’s subsequent book, In Cold Blood, remains a marvelous read, making me happy he fed off the killers until the moment their necks were broken. Still, real life suggests Capote paid a price for his five-year-long impression of a vampire in that he collapsed into full-blown alcoholism and never completed another book during the remaining two decades of his life.

Capote might be guilty of selling his soul to complete his masterpiece, but General Mireau in Paths of Glory is an arse-covering coward that cooks up a scheme to murder three scapegoats in order to save his blushes. But that’s one of the unfortunate things about the death penalty – most administrations have a rich history of abusing its purpose. Today Middle Eastern countries like to label naysayers, opponents and anyone pushing for regime change as ‘terrorists’ and dispose of them accordingly. It’s murder hiding behind the pretense of legitimacy.

Mireau (George Macready) is introduced living in opulence, an out of touch divisional commander that talks the talk and likes to think of himself as anything but an ‘armchair officer’. His boss gives him an order to take a heavily defended German position known as the Anthill. Mireau initially calls the order ‘ridiculous’ and is even mildly offended when promotion is dangled before him if he does manage to accomplish the objective. “My men come first of all and those men know it, too,” he insists while pompously striding around his lavish room. “Those men know that I would never let them down. The life of one of those soldiers means more to me than all the stars and decorations in France.”

But this mild indignation and statement of integrity is phony. Mireau has already been seduced by the idea of career advancement.

During a tour of the trenches, we see he’s not just a glory hunter but a loathsome human being. He keeps trotting out the same lines to the men he meets: “Hello there, soldier. Ready to kill more Germans?” He doesn’t actually speak to any of them, let alone listen. It’s a charade that falls apart when his script proves useless with a shell-shocked soldier. The man keeps repeating his questions and barely knows where he is. When told he’s shell-shocked, Mireau grows angry. “There is no such thing!” he insists before slapping the disorientated soldier and demanding his immediate transfer. “I won’t have any other brave men contaminated by him!”

Things grow even starker when Mireau meets the honorable, sharp-minded Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) to discuss the upcoming attack on the Anthill. Mireau’s matter of fact acceptance that more than half of Dax’s regiment will be killed is appalling. It’s clear he has no concern for these men whatsoever, only seeing them as a stepping stone. When the suicidal assault falls apart, the bluster-filled Mireau unsuccessfully orders a captain to fire on the ‘mutinying’ troops, only to be met with a face-losing refusal that sends him over the edge. “If those little darlings won’t face German bullets, they’ll face French ones!”

Mireau, who now sees the regiment as ‘scum’, wants one hundred men executed for cowardice before calming down and demanding just three. The unlucky trio get picked because of chance, a grudge and one being a ‘social undesirable’ with their subsequent court martial a farce in every sense of the word. Defending counsel Dax knows he’s got an impossible job on his hands. “The case made against these men is a mockery of all human justice,” he rages, calling it a ‘stain’ on the flag of France. It’s not enough to save them, although at least one of the condemned gets to slap a priest in their death cell and contemptuously dismiss the man’s ‘sanctimonious, pat answers’ about the shit they’re caught up in.

Kubrick’s first masterpiece is a searing indictment of war, authority and the death penalty. It’s a staggeringly cold vision of the affairs of men, especially when a cognac-drinking officer at a swish party the night before the executions defends them on the grounds of morale: “These executions will be a perfect tonic for the entire division. There are few things more fundamentally encouraging and stimulating than seeing someone else die.”

Collateral damage: Clyde Percy in Dead Man Walking & Piotr Balicki in A Short Film About Killing

As the father of a murdered teen, Percy (R. Lee Ermey) is presented in a curious way. Filled with righteous fury, this is a man who understandably wants to kill Poncelet himself. “You’re gonna fry,” he tells the cocky, taunting twat outside the courtroom. “I’m gonna watch you sizzle.” There’s a moment where he considers grabbing a trooper’s gun and finishing him off, later thinking if he’d gone through with the murderous impulse he ‘would have been a happier man today’. Percy is unwavering in his support for the death penalty, telling a TV news reporter: “It’s the only way we can be sure they won’t kill again. Life without parole? Oh, sure. How many prison guards and other prisoners do they have to kill before it’s over? These people are mad dogs. Maniacs.”

It’s clear the hardened Percy is going through an experience he won’t ever recover from, the acidic hatred set to gnaw his insides until the day he dies. Dead Man positions him as a figure of pity, especially when placed alongside the other grieving father (who half-attends Poncelet’s funeral) and Sister Prejean’s ‘face of love’. We later see this pair praying together in church, as if this is the correct and mature way forward, but there’s no post-execution shot of Percy. Has the removal of Poncelet brought him any relief? Does state-sponsored vengeance work when it comes to the tricky matter of emotional and psychological repair? Dead Man, a shiny, much decorated product of liberal Hollywood, remains silent, perhaps terrified to suggest that a front row seat in the theater of revenge might actually provide a cathartic peak and form of closure.

In A Short Film About Killing the sensitive, decent Balicki (Krzysztof Globisz) has just passed his bar exam and is looking forward to the rest of his career as a public defender. “I’ll be able to meet and understand people…” he tells his pretty wife. “Everyone wonders if what they do has any meaning.” In a strange quirk of fate he later learns that Lazar, the murderer whose life he will soon doggedly try to save, happens to be at the same cafe he chooses to celebrate in. “Perhaps I could have done something,” he muses while his optimism and idealism about Poland’s justice system crumble to dust. Killing’s final shot of the distraught defense lawyer (in common with Last Dance) is way over the top for this particular reviewer, but it’s clear that Balicki’s up close and personal experience of the death penalty will only make him hold his newborn son tighter.

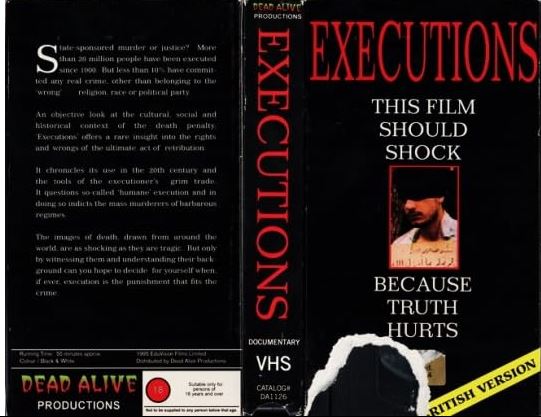

The real thing: Executions (1995)

This graphic 55-minute documentary wears its heart on its sleeve by immediately stating the death penalty is a ‘barbaric abomination that has no place in civilized society’. Then again, have you ever seen a doco or movie that’s in favor of such skylarking? I can’t think of one.

Starting with the 1792 invention of the guillotine (a device that would bring ‘equality and humanity’ to death), Executions maintains there’s no such thing as painless or clinical capital punishment. However, the anecdotes and stats it trots out in support are hardly conclusive e.g. an early twentieth century French physician attends a guillotining after which he believes a severed head retains consciousness for thirty seconds. Later we’re told electrocutions can take eighteen minutes to extinguish life while dangling on the end of a rope might take fifteen, but no footage of such prolonged death agonies is revealed. Instead we get grainy recordings that appear to contradict the doco’s thrust. For example, Chiang Kai-shek’s soldiers in the 1930s are repeatedly shown putting brain-obliterating bullets in the backs of their kneeling victims’ heads. Once those triggers are pulled, no one even twitches again, more than suggesting some forms of death are instantaneous.

Executions’ most interesting segment is its brief analysis of lethal injection, a procedure invented by the Nazis that has come to replace lethal gas in many American states after the botched, twenty-minute 1992 execution of a San Quentin inmate. “Lethal injection is the most extreme example of this century’s attempt to make execution look like medicine,” the narrator tells us. “Prisoners are killed on hospital trolleys. A machine releases poison and takes the responsibility for killing from human hands. A curtain opens to allow witnesses to see the execution as medical theater.”

This incisive commentary complements the threat of death hanging over Dead Man’s Matthew Poncelet when his defense attorney stands before an appeal hearing and initially runs through history’s many appalling methods of capital punishment. “Now we have developed a device that is the most humane of all: lethal injection,” he says. “We strap the guy up. We anesthetize him with shot number one. Then we give him shot number two and that implodes his lungs and shot number three stops his heart. We put them to death just like an old horse. His face just goes to sleep while inside his organs are going through Armageddon. The muscles of his face would twist and contort and pull but, you see, shot number one relaxes all those muscles so we don’t have to see any horror show. We don’t have to taste the blood of revenge on our lips while this human being’s organs writhe, twist and contort. We just sit there quietly, nod our heads, and say justice has been done.”

Executions states this process takes up to twenty minutes. It insists technological advances will never help provide a pretty exit, but if you’re truly anesthetized rather than merely paralyzed what does it matter? After all, anesthetics are so powerful these days that a surgeon can saw your leg off without you feeling a thing. To this ignoramus it seems perfectly possible that a painless death can arrive without an injected prisoner having the slightest clue (in much the same way some countries practise assisted suicide).

If nothing else, Executions is an interesting history lesson that covers everything from Stalin’s determination to wipe out the Kulaks to Saddam Hussein dropping poison gas bombs on the Kurds. It’s not particularly focused (straying far too much into genocide, ethnic hatred and mob violence rather than the state-sanctioned killing of convicted inmates), but it did make me think about the anti-capital flicks above. Apart from doing its best to convince us that the death penalty is nothing more than an ‘act of mob revenge’, Executions also shows the movies get it overwhelmingly wrong when depicting shootings. There’s nothing theatrical about being shot. No one throws out their arms, is hurled backward, looks skyward or does a silly little jiggy dance à la Bonnie and Clyde. You just drop, as if your legs have been kicked out from under you.

I guess it’s also a bit of a surprise that when it comes to the big, bad deed, films like Dead Man and In Cold Blood trip up by inadvertently depicting it as an efficient method of killing. Just look how easy Barbara Graham drifts off to la la land in her cyanide-filled gas chamber in I Want To Live! Wouldn’t it be more effective propaganda if she thrashed around? After all, Executions tells us a form of death like electrocution can fill the room with the smell of burning flesh before a prisoner’s eyeballs pop out of his or her head. Hmm, is this the next thing we can look forward to in the wonderful world of anti-capital punishment movies?

Leave a Reply