Family dramas and a cooking motif combine well as the metaphor is a universal one. A family, even one’s own, is a complex bouillabaisse, the outcome of which is impossible to predict based on what seemed to be simple ingredients. Secret of the Grain is not as sprawling as a Desplechein work, but it approaches its best with well-defined characters and a plotless meander with themes that defy easy description. The simple blurb would be “a patriarch loses his job and opens a restaurant on a boat with the help of his family”, which is kind of like saying the Arc de Triomphe is a bunch of bricks and mortar.

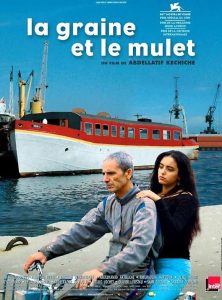

Slimane is an old man, and Habib Boufares was cast ideally for this purpose. He still works in a shipyard repairing boats, and he does his work with care and deliberation. As the film opens, he is losing his job for being too slow, soon to be replaced by someone younger and hungrier, and likely a cheaper immigrant in that common theme of economic change that will never lose its relevance. Slimane’s face is the very picture of world-weariness; kind, weathered, seeming to push forward through sheer force of will than any biological propulsion. His was a life that was eventful, but his fatigued visage seems to reflect a lack of substance to show for all that effort.

All he has is his family, and we meet them soon enough as he shuttles a bag of fish to each of them, all turning him down. They get plenty of fish, just not enough financial support. He is divorced from his wife, and the split between them is never explained. One gets the impression it was due to many factors that added up over the years than any one cataclysm. His sons and daughters are low-middle class and get by, none that comfortably, with scenes in crowded homes that have no room for Slimane. He moves slowly, and is the gravity at the center of a vibrant family that has little use for him. The only person close to him is the twenty-year-old daughter, Rym, of the woman who owns the hotel where Slimane lives (and whom he sleeps with).

Played by Hafsia Herzi, Rym is an unusually forceful and ambitious woman, a part that would flop if not for the intense conviction of the actress playing her. With a combination of sharp intellect and combustible sexuality, she crafts a character that becomes the foundation for what plot does occur in the film. Slimane is hopeful for a legacy of some sort, a way to prove he actually did walk the Earth briefly before returning to ash. As he is ripping apart an old boat that has been abandoned, he sees himself in the vessel soon to be reduced to scrap. Rym is the catalyst, the optimistic cinder to set flame to Slimane’s last hurrah. In the lives we lead, we generally bounce aimlessly from one task to the next, fulfilling socially acceptable goals with surprisingly little thought given, until we die.

Occasionally, we step outside our comfort zones to embark upon something of great import, perhaps unwisely, or possibly insanely. This generally does not work due to unforeseen circumstances, and maybe we refine the process until we get it to work, or at least take solace in our ambitious failure. This is how community centers, nonprofit organizations, or wildlife conservation projects take flight; the things so essential to holding our chaotic world together are borne of such folly. Slimane is building a restaurant on this decrepit freighter, a way for his family to do something truly special in their neighborhood. Discard and destroy is the ethos of our age, and Slimane’s desire to rehab the vessel is anathema to our worldview. His hubris is modest, but he feels at heart this must be done. This project won’t change the world in general, but it will surely change theirs. Perhaps at long last he could dare to be the provider he always wanted to be.

The remainder of the film (after over an hour of setup) is spent in realizing this dream, made impossible by a lack of restaurant management experience, business connections, and funding. Yet it comes together anyway near the end as local interests, financiers, and other people who could make a project happen coalesce in an inaugural dinner upon the boat. The centerpiece of the dinner is Slimane’s ex-wife’s couscous, legendary among the people of the community. His children, some good, some worthless, must help, each an essential part of the contraption, with a single dysfunctional part toppling the elaborate mechanism. Should an old, washed-up man dare to reach so far beyond his grasp? There is no real answer to this.

The film is held together by a series of wonderful scenes that play as though filmed in real-time using real people in their real kitchens and community sidewalks. This gives Secret of the Grain a very natural and lived-in feel that dispenses with artificial sentiment and unlikely positivity. These are flawed people, greedy and self-destructive, and so resembles the film’s audience. In one scene, a group of men lounging at a coffee shop discuss the stupidity of setting up a business concern on a boat that looks to sink at any moment with no money, no port authority to moor at a quay, and throwing a party specifically to obtain these things.

This serves as exposition, but more importantly their clucking gives you a sense of how such things fit into the community. Everyone is a skeptic, and these men provide one perspective to whether ambition is worth the effort. After all, they would be perfectly happy with olives and bread – why should Slimane hope for more? Another great scene is where the family assembles for their usual dinner, topped by the amazing couscous that properly takes the center of the table. They bicker and grouse, but they also laugh and love, and you become enveloped in this family for the film. One daughter is all about everyone’s business, and a son is chasing skirts so often he gets calls at his mother’s house. You feel a growing unease about where it all heads – we know the problems that come with family and survival, and when you depend on family for survival.

Strong themes abound in cultural and national identity – many of the characters were immigrants, or are second generation, and there are complaints about the mercenary attitude of the new wave of immigrants entering France. Rym in particular is passionate about the audacity of moving to a country just to earn and leave, rather than setting down roots in the nation where you learn to survive. “What is France? A whorehouse?” She has a vision of what it means to be permanent in a community, even as global populations are in a state of extraordinary flux.

She believes in the sanctity of the individual, but also the value of sacrifice to community, as a viable neighborhood is a living, breathing entity of its own, greater than the sum of its parts. One sees this belief bleed through in two scenes, one where she browbeats her mother into attending the dinner despite the expected commentary from the women of Slimane’s family. The other is a jaw-dropper of a finale, where she takes center stage to save the party from disaster by force. Her performance is astonishing, and one expected from an actress in the craft for several decades. This is Hafsia Herzi’s first feature film, and like Everlyn Sampi of Rabbit Proof Fence and Yurgul Nesilcay of The Edge of Heaven, it is a revelation out of nowhere. Such gestures make it clear that though the stakes presented here are modest, for the people of this family, those stakes could not be greater.

Our protagonist is a simple man, and for the first time he attempts something truly complicated for reasons even he does not truly understand. As complex things tend to, these plans begin to fall to pieces. What holds his unstable patchwork together is family – of a sort. As the grain unifies the dish, these people so hastily assembled over a lifetime of worry and regret come together with our man at the center.

As the unexpected conclusion seems to make clear, there is no truth to ‘too little, too late’, even if things do not go as expected. It is all too easy to look in retrospect at such a unlikely grasp for victory. If the attempt was successful, we imagine we would have tried as well; if it was an abject failure, then of course we never would have bothered. When you are caught up in the moment, you never know whether fortune will favor your desire. My interpretation of the enigmatic final shot is that it is always worth a try, regardless of the outcome. So it is with the things we care about.