Ingmar Bergman 1918-2007

Webster’s dictionary defines “saraband” as: “a stately court dance of the 17th and 18th centuries resembling the minuet,” or “the music for the saraband in slow triple time with accent on the second beat.” Given this, how appropriate indeed that Ingmar Bergman conclude his remarkable career with a tribute to the sound of the human heart; a stark, painfully realistic assessment of the journey’s end, both for human beings in general and for the director himself. Bergman has announced that this will be his final cinematic feast, a fact that should depress all who value the sort of introspective filmmaking that has largely surrendered to mindless spectacle. Saraband is a striking rebuke to everything the movies have become; a process that takes any viewer back to the days when characters bared their souls with such raw honesty that we wonder whether or not we have earned the right to continue listening.

There are no clever winks in the course of the film; no ironic nods that allow us a reprieve from the pain. Either we choose to follow these characters through to the end, or we detach and damn the effort. And so, we return to the musical motif. To paraphrase one of the characters, we spend our whole lives trying to learn the saraband, and only at the end of our days do we truly come to understand its details and undercurrents. Most are not fortunate enough to learn it at all, but it is infinitely more painful to reach a state of self-awareness and truth when we are no longer able to effect real change. Some may be comforted by a deathbed conversion, but Bergman sees such melodramatic tricks as the ultimate tragedy. If we cannot look inward and reach out to those we have hurt while it still matters, then it is best to slip away without any last-minute effort.

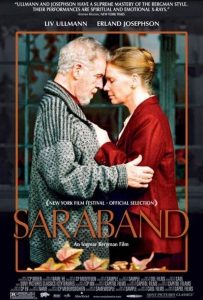

The end of life is defined by regret and sorrow, and for Marianne (Liv Ullman) and Johan (Erland Josephson), characters we first came to know in 1974’s Scenes from a Marriage, such certainties hold firm. And while these are the same characters, now aged by 30 years, this is not a sequel so much as a reckoning; 10 “scenes” that are in fact conversations, only a few of which involve the pair. Marianne speaks directly to the camera in the prologue, casually informing us of her plans to visit Johan, although she’s not exactly clear about her intentions. The obvious answer would be that she wants to see how the father of her children is getting along these days (or to quietly gloat if her life has turned out better), but this may be her way of saying goodbye to a man she once loved (and then hated), though now, she feels little more than the solace of closure. At first, she creeps along his isolated retreat (she calls it a “lair”); a prison of sorts that he was fortunate enough to receive in an inheritance.

Now an old man in his 80s, he is predictably asleep when Marianne decides to wake him, and he seems less shocked by her appearance than we might expect. As they catch up in those first moments, there is something unspeakably sad about the whole affair. From Johan’s almost instinctive efforts to hold hands or embrace, to Marianne’s quiet dignity, we realize at once that this is what becomes of us all, even if thoughts of mortality remain at the forefront of our minds. We know we’re always considering the aging process (even obsessing over it), but somehow, it still remains an abstraction – something “they” do, but somehow avoids our proximity. Because Scenes from a Marriage was such an intense, exhaustive look at the arc of a love affair, seeing these two people together – still whole but having lost at least a few steps – brings it all back, only with a bit more perspective.

The central relationship is between Johan and his estranged son Henrik (Borje Ahlstedt), a man in his 60s who has yet to find himself and continues to mourn his deceased wife, Anna. Anna’s presence is felt throughout this film, whether in terms of her picture or as the topic of conversation, and it is clear that she remains an idealized woman for more than one character. In fact, Anna is memory itself – how it continues to punish us through the years, and how it remains complicit in distorting or falsifying the past. For these people, however, memory is a torture chamber; a cruel device that steadfastly refuses to allow forgiveness or unconditional love. One of Bergman’s essential truths – here and elsewhere – is that despite our discussions, debates, conversations, and probing analysis, we die much as we’ve lived. Change is largely illusory. Fathers and sons hold grudges and play power games that humiliate and scold, and by the end of the road, nobody has any idea as to how it all got started.

Perhaps there’s something about it that’s built into our very DNA; that the relationships that sustain us are the very ones that destroy us in the end. Perhaps it’s unavoidable, then, that the ties that bind breed a unique form of emotional perversity. And if we make the attempt to steer clear of its influence, the relationship itself will seem troubled, almost forced. There’s a particularly nasty scene in a church where Henrik confesses to Marianne that if he could, he would chronicle every last second of his father’s painful death and have absolutely no concern for his suffering. It’s not enough to have the old man dead; he must sense his decay through every waking moment. It speaks volumes about the human race that words such as these could only be said by family members to one another. Our interactions with strangers seem loving by comparison.

Henrik has demons that go beyond his broken relationship with his father, however, for he is passing on the same unyielding pain to his own child. Yes, he is battered by the death of his wife, but he is so demanding and unfair that it’s only a matter of time before she strikes out in the most unimaginable ways. To compound the pathology, Henrik and his daughter are engaged in an incestuous affair, which is obviously the result of Henrik’s recent loss (and a deeper sickness, needless to say). Thankfully, there’s nothing sordid or exploitive about any of this, which is a testament to Bergman’s insistence that the audience be treated like adults, rather than leering children looking for a cheap thrill. It’s a development we half expect, but only because Henrik immediately strikes us as the type of man who is uncomfortable unless he is channeling his rage into a pain he can inflict on others.

There’s a suicide attempt when his daughter leaves for a conservatory (she’s a gifted cellist), but again, this is not a dramatic device so much as the inevitable coming to pass. Bergman does not ever resort to cheap “surprises” or plot turns to pull us forward; he is a filmmaker of the emotions, albeit one who prefers the company of intellectuals, artists, and world-weary philosophers. One can see why Woody Allen would be such a devoted follower: In Bergman, we have a man who can at once elevate the language (and the art form) with high-minded dialogue, but who also demonstrates that those who would seem to have life figured out are usually most troubled by day-to-day reality. In other words, books are worth reading and infinitely preferable to television, but they’ll drive you mad. It’s the eternal price of wisdom.

As expected, Saraband is magnificently acted and lovingly directed, with Bergman’s usual understanding (and appreciation) of the human face. No one does the close-up quite like him. He insists on showing the ravages of age, although Liv Ullman is stunning in any language. If that’s 67, sign me up for some GILF lovin’. And in one of the film’s most powerful sequences, we even see Johan in the nude; an uncompromising vision of what we all become (or perhaps in my case, where I’ve already been). He stands before Marianne at his most vulnerable, reverting to a child just long enough to feel a sense of security. She welcomes him into her bed (she too is naked), but intercourse in the furthest thing from their minds. This is about acceptance; that much-discussed, but frequently overlooked, quality that so many crave, but just as many seem incapable of giving. Johan will soon die, largely unloved, and surely full of self-loathing, but he’ll take that moment, because over a lifetime, it’s often all we have.

And so, we bid adieu to Mr. Bergman, that master of the chamber drama and that chic Scandinavian pessimism; a giant among mortals who dared to ask the essential questions about God, existence, life, and love, and was just as comfortable admitting that few answers were to be found. That we’ll never have another film from such a man is enough reason to retreat to a dark room and sob well into the night, but looking back over a catalog of undisputed masterpieces, there is cause for hope. Few have done it as well, as often, and we owe so much to his willingness to crawl into the human psyche, where so very many fear to tread.