The first-person technique where the camera itself, and by extension the viewer, is the central character has been frequently abused to little effect since it was made famous by the Blair Witch phenomenon. Most often it is little more than a gimmick, useful only in disorienting the viewer and saving on the budget by obscuring the view that would otherwise be filled with special effects. The characters are usually lifeless, the plot dull, the director hoping to make some quick cash off an increasingly unfussy moviegoing public. Still, the potential power of the first-person device in the thriller or horror genres must be acknowledged. By forcing the viewer into the film itself, one acquires a subliminal stake in the action, and can feel those limbs and vital organs move into the line of fire. Losing the omnipotent perspective of the third person in standard films, you regain the uncomfortable limitations of the mortal character in a dangerous setting.

This is most true for horror films, where the tension is amplified by a relative lack of information on one’s adversary, and an inability to understand the threat. Jaws became a horror classic primarily from the scarcity of shark footage – it was an unseen danger lurking beyond one’s view, and remained unseen even after it left with your viscera. Halloween would never have been as gripping if the killer were anything more than a cipher; death itself perpetually enveloped in the nearby shadows. Sequels of these films failed to keep these ideas in mind, leading to an endless line of disposable jokes.

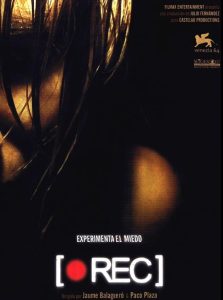

Every now and then, however, somebody gets it right. [REC] is that most effective of horror films, with characters realistic enough to understand and develop an attachment to, effective craft of a director who never lost sight of what makes the genre work, and lethal efficiency that stays with you after the credits have rolled. Though remade quickly and cheaply into Quarantine for Americans who are unable to read English subtitles (the original was filmed in Spanish), it would behoove you to give the first-person gimmick another shot.

The conceit is a sensible one– the characters are a crew working on a crap TV show working the night shift at a fire station, hoping for something interesting to film. The cameraman doesn’t speak much, but being a professional who will shoot anything compelling or dangerous explains why he doesn’t just put the fucker down and run when the shit hits the fan. The host of the show is a bubble-headed reporter who is more used to fluff pieces, and finds herself way in over her head. Though afraid, they resolve to record all they see as it becomes evident that tragedy is in process. They are not heroic, resourceful, or especially clever.

They are us, in all our mediocre glory, when they embark upon an enigmatic assignment. The firemen are called out to a fairly boring emergency call, some demented old bat in an apartment building is agitated, and has attacked one of her neighbors. Ordinary weekend night shift. Before the crew knows it, the woman has drawn blood, the situation becomes dire, and the entire building is sealed in plastic from the outside by heavily armed cops. No information is given to those inside, even by an infectious disease specialist who is inserted into the building. They, and we, do not know what is going on, but it is suggested that there is a good reason for the extraordinary precautions being taken. After 20 minutes or so of straightforward setup (and the pretty lousy reporting that one would expect from a cable-access news show), the mode enters full panic for the duration. There is nowhere to run and no help on the way.

Jaume Balaguero and Paco Plaza maintain an insane focus throughout, and the effect is, at the risk of cliche, pure adrenaline. If you can get past the artificial construct of the first-person perspective, and allow yourself into the action, you will rarely see a more effective thriller. There are no jump-cut scares that are the crutch of inferior horror films – every shock here is organic to the story. The no-budget verisimilitude makes what would be more pedestrian settings and images genuinely unsettling. Rather than rely on sets, the entire movie was shot in a small Barcelona apartment block, lending [REC] a claustrophobic look.

You can tell this was not made in Hollywood since it depends on the viewer to be thoughtful enough to glean information from tangential conversation, oblique references, and visual clues that imply an explanation without actually having one. There is no mystery that can be solved, but it seems as though there is one to figure out if only time and the rapidly moving infection would allow. And that is what makes [REC] a pure winner – everything we expect as a spoon-fed audience is kept beyond arm’s length. Information, a view of the action, a sense of what the characters are truly up against, and finally escape itself remains elusive until… Well, see it for yourself before it disappears from DVD while its remake is remade for the third time.