Sordid glory.

Would you call that the defining trait of writer Joe Eszterhas’ distinctive body of work?

After all, this is the man who cooked up Basic Instinct, Sliver and Showgirls in his steamy, body-filled kitchen. Most screenwriters dawdle in obscurity, even if their creative juice results in a colossal hit, but Eszterhas gained notoriety for his pushy persona, unapologetically racy subject matter and the enormous sums of cash he was paid. Indeed, Instinct resulted in a then-world record $3million payout. Or as he says in his bloated, lewd and self-aggrandising memoir Hollywood Animal: “I was the only screenwriter in the history of Hollywood who had groupies.”

Yeah, well, nice work if you can get it.

The former journalist began his politically incorrect journey toward Sharon Stone’s uncrossed legs with a distinctly atypical PG effort in the form of 1978’s F.I.S.T. It centers on workers’ rights and the growing power of the Federation of Inter State Truckers trade union while chucking in some gangsters and corruption. A miscast Stallone (in his first post-Rocky appearance) plays a Hoffa-like character, trying his damndest to convince us he’s a proper actor. This ultra-serious flick doesn’t really work, mainly because there’s nowhere near enough action to justify its two and a half hours. Most of the time it’s hamstrung by too many scenes of men standing around listening to speeches. Eszterhas’ screenplay is workmanlike. The dialogue’s reasonable, but there’s no flair or personality in the writing, especially when it comes to the supporting characters. It smacks of timidity, as if Eszterhas were on his best behavior.

Still, F.I.S.T. made some money (probably because Stallone was a hot property), giving Eszterhas the chance to hit the big time five years later by helping shape Flashdance. This energetic pile of great big daft fun turned into a $200m success, enabling Eszterhas to pen what I’d call his first true movie in the form of 1985’s Jagged Edge.

Now while Flashdance briefly offered strippers and nudity, it remained a romantic drama. Edge, however, shifts the focus to lust, murder, rich bastards, manipulation, unprofessional conduct, greed, red herrings, conscienceless killers, misogyny, the corridors of power, lots of twists and all those lurid Eszterhasian things we’ve come to love. It immediately delivers ample evidence of his vicar-offending imagination when a silent, ultra-confident killer creeps into a swish coastal property on a stormy night. Moments later he’s tying up a woman in a bedroom, ripping open her pajama top, and taunting her with the sight of his six-inch hunting knife before leaving the word BITCH daubed in her blood on the wall above the bedstead.

Well, my good friends, I’d argue that’s the moment when the fully formed Mr. Joe Eszterhas (warts, cigarette-and-Scotch-tainted breath, throbbing erection ‘n’ all) arrived.

What’s more, both the public and the critics liked his newfound blood and thunder approach. Edge is an intriguing adult courtroom drama with an excellent cast of nicely fleshed-out characters. The suave Jeff Bridges, whose handsomeness is almost off the scale, is a suspected wife-killer while the sincere, tough-talking Glenn Close is appointed to defend him. Now I’m not a lawyer, but I sense Eszterhas plays fast and loose with judicial and legal procedures. Mind you, that’s fine as long as the end result is entertaining and near-plausible. The mostly well-written Edge ticks such boxes.

Despite its daft climax, the gaudy pieces of Edge just about held together, but Eszterhas’ yen for the outlandish started gathering pace with 1988’s Betrayed. Its juicy subject matter of white supremacy dovetails nicely with his political incorrectness, as exemplified by an apple-cheeked five-year-old girl saying before bedtime: “We’re the good guys. One day we’re gonna kill all the dirty niggers and the Jews and everything’s gonna be neat.”

Debra Winger plays a committed but inexperienced FBI agent sent to infiltrate a Midwest race hate group. However, this premise is merely the first in a series of implausibilities. Would a rookie really be given such a dangerous mission, especially since these guys are already suspected killers? Then Eszterhas has Winger witness a murder during a racial version of The Most Dangerous Game, the FBI decide that’s not enough evidence as they lack a body, and ten minutes later she’s winging a twitchy security guard Patty Hearst-style in a fund-raising bank robbery.

Hmm, say it ain’t so, Joe.

Yeah, well, I still enjoyed the well-performed Betrayed, even if it seems a lot less well-known than Eszterhas’ other work. There’s no doubt of the glee in the writing, especially if you compare the dialogue to the conservatism of F.I.S.T. The best bit involves our well-connected, hiss-worthy villain Tom Berenger taking his family to a summer camp deep in the woods to meet a lovely mixture of cross-burning Klan, Christian fundamentalists, homophobes, a warped politician, neo-Nazis and Confederacy-supporting fuckwits. Here children are taught to fire at golliwog targets while swastika-adorned salesmen proffer authentic WW2 Lugers. You can even buy a Hitler birthday card! Betrayed’s main strength, however, remains its relevance. I have little doubt that there are still moms across America serving up apple pie while casually remarking: “It just ain’t the same country I grew up in, that’s all. The bad just pushes out the good. There’s filth and trash everyplace.”

Eszterhas returned to the courtroom for 1989’s Holocaust-flavored Music Box. This is a good movie to shove below the sneering noses of the anti-Eszterhas brigade, those tutting hand wringers who believe dollops of uber-profanity and hateful sexualised violence are his raison d’être. Music Box is a methodical, well-constructed drama led by an on song Jessica Lange. She’s the lawyer daughter of an accused war criminal, Mike Laszlo (Armin Mueller-Stahl, also excellent.) He’s a man who fled Communist Hungary in the early 50s to start leading a model life in Chicago. “What do we know about our parents?” Lange is asked by a colleague. “Oh, I know him,” she replies. “He raised me.” This simple statement, of course, forms the crux of Music Box’s attack: how well do we know other people, especially our nearest and dearest? Most of us can’t even handle the thought of our parents doing normal stuff like having sex, let alone the slightest suggestion that they’re capable of stone cold evil before we were even conceived.

Nothing is sensationalized here. There are no cheesy flashbacks or re-enactments, no violence, and little wailing or gnashing of teeth. Instead Eszterhas blends in some bone-chillingly banal details that ring of truth, such as Laszlo’s fondness for push-ups (“A healthy body makes a healthy spirit.”) Eszterhas’ dialogue also deserves praise, especially the words he gives to a series of Hungarian prosecution witnesses who recount what it’s like to be up close and personal with an SS death squad. Ultimately you can criticize Music Box for its predictability and the way it fails to come up with even the slightest explanation for monstrous individual evil, but it’s still a mature, convincing picture that succeeds (in spite of Lange’s horror hairdo).

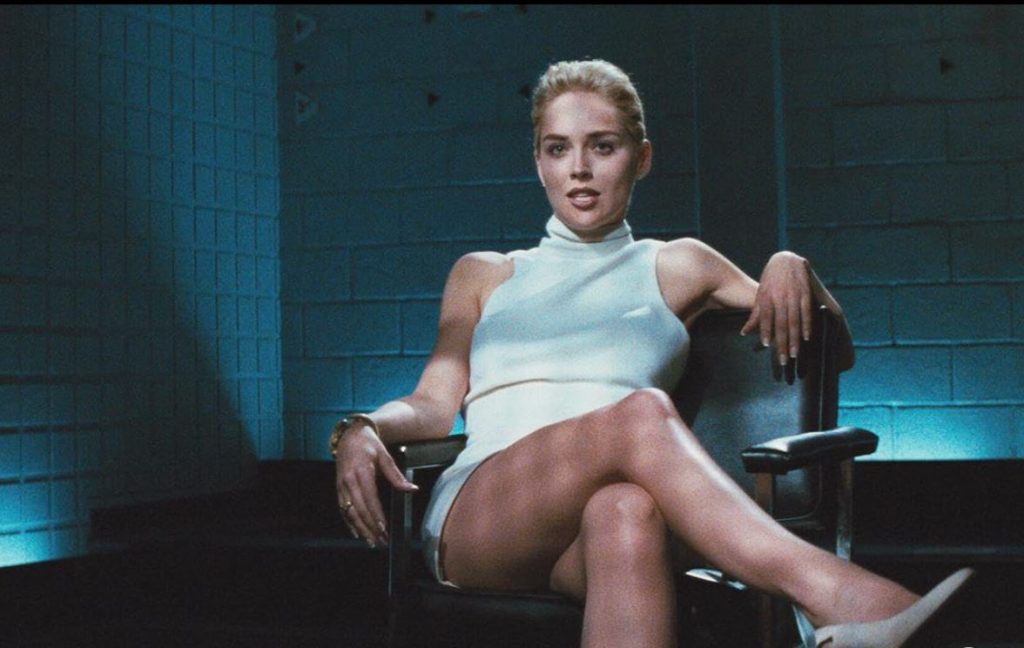

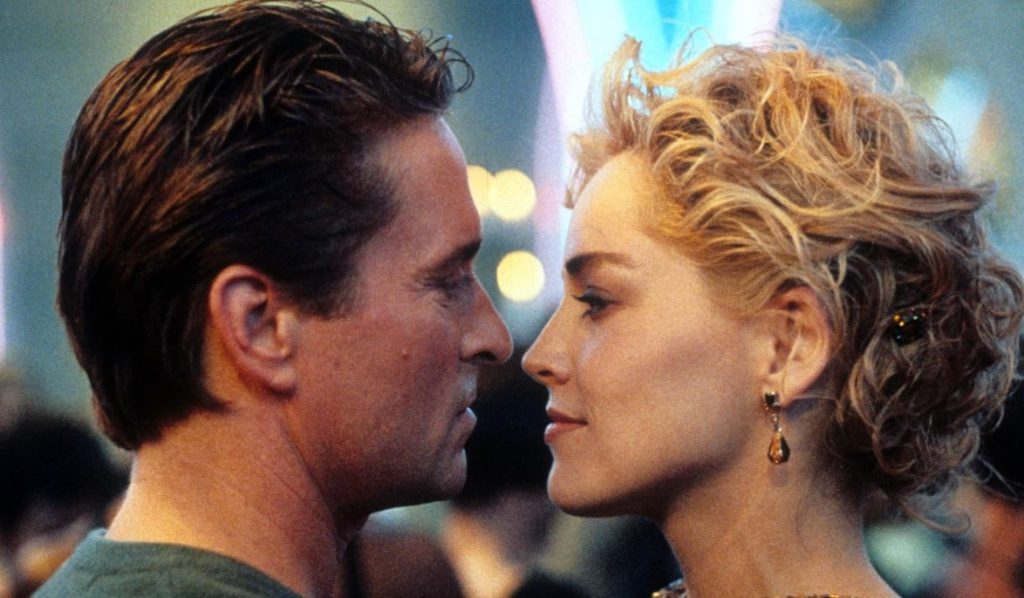

Next up was Eszterhas’ commercial peak, Basic Instinct, a $350m box-office monster. It remains divisive, hated by The Gays and their pink-clad liberal friends, but I don’t have any doubt folk will still be watching in a hundred years, having long forgotten the more restrained and respectful stuff released around the same time. It’s also interesting to note that Instinct’s most notorious scene wasn’t penned by Eszterhas.

It was Verhoeven that came up with Stone uncrossing her legs, resulting in arguably the 90’s most iconic cinematic moment. This is a good example of how tricky it can be to judge screenwriters, given that their scripts are often wildly altered. Case in point: 1993’s Van Damme vehicle, Nowhere to Run. Eszterhas has pretty much disowned it. “Robert Harmon was the idiot who directed Nowhere to Run,” he writes in Hollywood Animal. “He turned my screenplay inside out and I wrote him a long memo explaining his genetic failings. He read the memo and suffered a heart attack afterward. Such a young man, too, tsk-tsk!”

But then you suspect Eszterhas is such an egomaniac and control freak that he resents any changes to his words. Compromise, a favorable response to constructive criticism or an acknowledgement that moviemaking is a collaborative process is simply not in his DNA. “I wasn’t there to serve the director’s vision,” he states. “The vision was mine and the director was there to serve it: to translate my vision to the screen… I viewed myself as the composer. The director was the conductor. The others were parts of the orchestra.”

Oh, well, whatever the truth, I still have to write up Nowhere to Run. Of course, it’s a sappy disappointment after Instinct’s PC-shredding glories, but its decent opening fifteen minutes (complemented by a plethora of pleasant scenery) suck you in without difficulty. I also quite enjoyed Van Damme’s subdued performance as an escaped con wangling his way into Rosanna Arquette’s young family. Here he starts off as a peeping tom before inadvertently getting naked in front of her small children. “He’s got a big penis,” the impressed six-year-old daughter later tells mum at the dinner table.

Bad guy developers, who want Arquette’s rural land, soon show up, enabling Van Damme to bust out his head-cracking moves, make tigerish love to Arquette a few hours after having his kidneys savagely beaten, and look cool on a restored Triumph motorbike. Harmon might be an idiot (according to Eszterhas), but he still manages to come up with a straightforward, nicely filmed watch. Somehow I doubt the grizzled Eszterhas penned any of those bloody soppy kid-friendly scenes, though.

Sliver, however, is undoubtedly classic Eszterhas territory with its whodunit aspect, rampant voyeurism and bathtub wanking. Reuniting our main man with Sharon Stone, it grossed nearly $120m but was probably seen as a pallid box-office disappointment next to Instinct. And it’s easy to see why. Sliver is a sexed-up turkey, devoid of zing or oomph, which once again has Stone going sans underwear in a public place.

She’s a bookish book editor (ready for ‘new orgasms’) who moves into a hi-rise New York building. She immediately has to endure Tom Berenger being a tool in every scene, William Baldwin looking like a skinny young Robert Mitchum with Down syndrome, and a female flatmate complaining that moving house is ‘worse than anal intercourse’. Huh? Only an Eszterhasian character could compare changing addresses to butt-fucking. Sliver is a so-called erotic thriller that’s neither erotic nor thrilling. The bloody thing just drifts and meanders, leaving Stone to vacuously grin as she plods through the crappy, forced dialogue and diabolical goings-on while trying to find a plot.

Showgirls followed, a movie so idiotic that it has since attracted an army of devotees unable to get enough of its scenery-chomping, twat-foaming absurdity. That randy old dog Eszterhas still pocketed millions for his atrocious script, though. However, it died at the box office, leaving him in need of a hit. Unfortunately, he came up with 1995’s Chinese-tinged Jade, a pic that clawed back less than twenty percent of its $50m budget. I dunno why as I quite enjoy the first hour of its heady mix of profanity, flies being unzipped, blackmail, groovy violence, a nympho super-hooker and a car chase down San Francisco’s mad hills. Perhaps the movie-going public objected to a ginger (David Caruso) being cast as a leading man in an erotic thriller. Maybe they were tired of the glut of sexually aggressive flicks that materialized in the early to mid nineties. Like I said, I dunno, but I found this William Friedkin-directed effort fast-moving and fun, although barely anyone else seems to rate it.

Caruso is an assistant DA investigating the hatchet murder of a prominent businessman in his mansion. Eszterhas quickly throws in a corrupt, pussy-happy governor, tufts of pubic hair kept as trinkets, a ‘fuck house’, Michael Biehn sporting an unfortunate tash and, I believe at one point, a brief shot of a stiletto up an anus. Some of the salty dialogue (“I do the fucking, I never get fucked”) harks back to Eszterhas’ salacious best, but after a focused, excellent hour or so Jade does become an unwieldy pile of nuts. It also proved to be the swansong for his particular brand of sleaziness. Hollywood is simply not the place to pen two flops in a row, meaning Eszterhas’ blood and spunk-spattered salad days were over. He might have gone on to write another handful of unsuccessful flicks, but none contained his trademark smut.

And so what will the final verdict be on this Hungarian trashmeister? No doubt some of his harshest critics will regard him in much the same way as the last line of Jagged Edge: “Fuck him. He was trash.” Clearly, Eszterhas was never interested in (or capable of) creating high art. He much preferred (while perhaps bringing his own fantasies to celluloid life) to try to get bums on seats. Indeed, you’d have to hail him an overwhelming success in this regard because despite the numerous flops, his films still generated more than a billion at the box office. Critics really do need to take such a sum into account because it does seem that for a short period he gave people exactly what they wanted. No screenwriter has ever had a higher profile, as clarified by Hollywood Animal in which he claims he used to get two thousand fan letters a week.

And despite being long accused of a misogynistic, contemptible output, actresses of the caliber of Lange, Close and Winger all benefited from his creative energy while Stone, of course, was handed the role of a lifetime. Would his amped-up, in-your-face films like Basic Instinct and Showgirls still get made in Hollywood’s much more PC environment today? Probably not.

Make of that what you will.

Leave a Reply