As banal as it appears, The Mother is in fact the most appropriate title for this film, as its central character is a woman who has always submitted to the definitions and expectations of others, rather than speaking her own mind and carving out her own identity. She has always been a wife and mother, although not necessarily a good one from the standpoint of those in her care. Having played by the rules and taken care of her husband’s needs, she has put harmony above all else, and as a result has an air about her that speaks to the sort of quiet resignation one feels after a lifetime of sacrifice.

She did her duty, so to speak, but at life’s end, will anyone remember what she did? Hearth and home were run with efficiency and care, but as one fades into the misery of age, are these memories even worth recovering? For her, then, the only way in which to rescue her dignity is to risk it all for a bit of the old hot cock. And not just any cock, mind you, but one belonging to a man young enough to be her son; a man who is also dating her daughter. In this way, she does much more than rage against the dying of the light, she falls to her knees and swallows it whole.

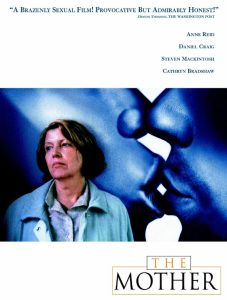

As played by Anne Reid, May is a sensible, quiet woman who has recently lost her husband of many years, and is afraid to return to an empty house. She floats between the homes of her son and daughter, and it is at her son’s place where she encounters Darren (Daniel Craig), a bearded handyman who is just the sort to awaken long-buried feelings in an aging tart-in-waiting. May is forced to endure her self-absorbed daughter’s ramblings about her writing “career” and stormy relationship with Darren, who is still married and also has an autistic son.

It is one of the master strokes of the film that we never meet this kid, as it spares us offensive displays of mawkishness that are standard in most Hollywood productions. But this is a British production, and they usually know better. May is also not the sort of woman to get upset at her spoiled children, although I did hope that she would have smacked them around a bit just to let off some steam. Instead, May decides that after decades of accepting her fate as a doormat, she will flirt and, if necessary, suck cock with the best of ’em.

We can tell from the start that Darren is simultaneously appealing and a bastard waiting to have his big meltdown, which is just right because May’s affair must never become too “fulfilling.” It is right and good that she indulge in a bit of pleasure at her age, as she has gone most of her life without putting her needs first (sexual or otherwise). And at first, Darren is more than a rugged hunk, but also a caring, gentle soul who never questions the basis of their relationship. At one point May asks that he take her up to the spare room, and he obliges without much thought. For Darren, we assume it’s a matter of sex and in the end, a woman is a woman, but he’s smooth enough to cater to May’s fantasies.

They have lunch, maybe a spot of tea, then they go at it like two randy teenagers. Normally my stomach would empty of its contents at the thought of grandmothers getting porked, but in The Mother it was handled with grace and humanity, without ever resorting to cheap sentimentality. It does best in the way that it shows May to be as selfish as the other characters. She is justifiably needy, but it must always be remembered that she is fucking her daughter’s lover. May is smart enough to know that the affair will be discovered (she even suggests that they hit the road for several months, seemingly heedless of the consequences), so perhaps the whole thing reflects a subconscious need to punish her daughter. After all, her daughter is but one living reminder of why she was so miserable and dependent to begin with.

The story arc of The Mother holds few surprises, but it is presented with such solemnity and maturity that I never cared. Even a date with a man her own age was somewhat expected, but not what it ended up saying. May is set up with a member of her daughter’s writing group, and the two have a few awkward meetings before finally settling down for a shag. May seems to give in not because she’s attracted to this man, but rather out of that sense of duty that remains from her past. After all, isn’t it preferable that an older woman stick with older men? Isn’t that the proper thing to do? Their sexual encounter, at least from May’s standpoint, is dreadful, as the gentleman goes through what could be mistaken for a heart attack in what must stand as the least erotic sex scene in the history of the cinema.

But the scene is not played for laughs. I firmly believe that the film is siding with May and her selfish, reckless relationship with a much younger man by demonstrating her disgust with brittle bags of bones her own age. If she isn’t attracted to old, wheezing lions in winter, then why should she be compelled to date them, or even hit the sheets? If she wants a strong, confident member in her mouth rather than a tired, shriveled piece of beef jerky, then who are we to judge? The heart wants what it wants; doubly so for the nether regions.

In all, The Mother is sassy, serious, and one of the few assessments of adult relationships that doesn’t insist that a one-liner will save the day. These are complicated people making difficult decisions with their lives, with nobility being merely optional rather than mandatory. The characters reflect the often overwhelming pressures that hit us all, especially as we realize with a thud that life offers little guarantees outside of persistent disappointment. And the film asks us to consider what constitutes the role of parent, even when our duties are no longer related to feeding and tucking the brats in for the night. And without hitting the point too hard, the film also suggests that it is both unfeeling and understandable that we want our parents to go away as they age, if only because we have enough on our minds as it is.

Few joyfully send their folks off to the screeching, piss-filled houses of horror that are old age homes, but it is not blasphemy to say that when they do, it is not always the worst possible decision. But May isn’t ready for round-the-clock bingo quite yet, and her final scenes are both triumphant and tinged with a bit of sadness. She’s doing what she wants to do — and doing it alone — but we are left with no guarantees that she’ll find the happiness she seeks. Or perhaps it isn’t happiness after all, but only the realization that, good or bad, she has no one to rely on but herself.