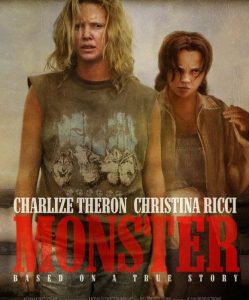

Patty Jenkins’ Monster closes with the following lines of dialogue, spoken as a voiceover by Aileen Wuornos (Charlize Theron) as she is led away from the courtroom to her cell, where she will spend the next twelve years before her execution in 2002:

“Love conquers all. Every cloud has a silver lining. Faith can move mountains. Love will always find a way. Everything happens for a reason. Where there’s life, there’s hope. Well, they gotta tell you something.”

In many ways, that bitter, yet knowing passage is the central truth of the film. While I have no idea whether or not the real-life Aileen uttered those words, they capture the essence of the character we see on the screen — a deluded, shattered woman who shares the same dreams and ambitions as everyone else (job, house, car, a sense of belonging), but lacks the necessary skills to achieve those ends, as well as the emotional and intellectual grounding required to understand them. All that she knows of life, or what one is supposed to desire, comes from an imaginary world; a fantasy of movies, music, and pop culture, filtered through a life of abuse and betrayal.

Aileen is, of course, responsible for her crimes and it is clear that while one or two of her murders might have been the result of attempted rape, robbery was the primary motivation. Therefore, I should not have to explain that she is a selfish, reckless, violent woman with little or no conscience, but it seems that unless I do, my explanation of her actions might be deemed “sympathetic.” I am not, and she is not. She kills for personal gain, and she does not consider the lives she is forever changing as a result of her brutality, although there is one scene, likely fabricated, that has her “pardoning” a shy, stuttering man who claims to have never before solicited a prostitute. This scene can serve only one purpose; to demonstrate that Aileen’s murders are no doubt connected to a sense of revenge against the horrible men that have brutalized her in the past. That she spared one life because he “wasn’t like all the rest” is a way to humanize her plight. After all, no one kills in a vacuum. There is, and always must be, events that precede seemingly “random” violence.

And then there is a sociological explanation, one that comes from my college days (forgive me) and can only be remembered as “society’s fault.” I realize that what follows will be dismissed by the Red States as typical liberal bullshit, but bear with me on this one. That theory states that when a given society sanctions particular values and goals as “The Ideal,” then constructs an environment in which large segments of its citizens are unable — through discrimination, unequal access, the assorted “isms” — to achieve those ends, they will, by necessity, carve out alternative pathways that circumvent the accepted route. Convoluted and silly? Keep reading, dear ones. And before you think it, I realize that not everyone resorts to murder as a result of failed dreams. Most people play by the rules, but when we look at how millions of people attempt to reach the pot o’ gold (which is, almost universally, financial success) — from prostitution, to drug trafficking, to murder for hire, to working for Halliburton — we can see that in a sense, we are all striving for the same thing.

A hardworking sap at the local discount store wants a better life and has decided to achieve that end through traditional methods, but what of the mentally unstable, uneducated low-life with few prospects for stable work? Unless they can turn off the drive for a better future, they must work with what they have. Therefore, they often turn to what we have declared to be “wrong” and “immoral.” Yes, a society is better off when it declares — and enforces through law — that violence, murder, and exploitation are detrimental and will be punished, but it is not the point to wag one’s finger. I only seek understanding. That is a far cry from endorsement.

And this brings me back to the quote that begins this review and ends the film. Aileen is, through the filmmaker, mocking the clichés that give so many the belief that better times are always around the corner. Americans especially hold to these empty inspirations, as we are told from birth that we can have anything we want as long as we scrap and struggle along the way. As such, we are defiantly optimistic people. But again, we fail to understand that while we all may be familiar with these words, not everyone has the tools to turn them into action. So, we casually dismiss these folks as lazy or foolish, and flatter ourselves into thinking that pure will is all that separates the penthouse from the back alley. Circumstances sound like excuses to us, and we’d rather not deal with unbearable pain and fundamental unfairness as part of our daily lives. And yes, “they gotta tell us something” because it is an unrivaled heresy to doubt the sanctity of the free market. We’d sooner admit that Jesus Christ was a drunken fraud then doubt the average man’s ability to rise from rags to riches. Ha, another cliché. We simply cannot escape them.

So where does that leave Aileen? As played by Theron (in a performance that redefines her career), she is impulsive and defiant, but when she tastes some aspect of that American Dream (in this case, love) she tries to position herself for legitimacy. Her strut and swagger are of a woman who feels uncomfortable in her own skin, yet she must project strength lest the bastards grind her down once and for all. She vows to end her life as a prostitute, secure honest work, and save enough money to buy her lover (Christina Ricci) a nice place away from the madness (Ricci’s character is herself a lost soul, a sexually confused youngster fighting her fundamentalist parents). Logic and experience tell us that Aileen will fail, especially when we watch her go on a series of hapless job interviews. In some ways, these scenes are unsuccessful, as they play for cheap laughs.

They are not slapstick by any means, but they could have been written with a bit more understated rage. The dialogue, especially on the part of a particular employer, seems crafted to elicit a colorful explosion by Aileen rather than anything that might really be said by an interviewer. Still, these scenes do establish the futility of Aileen’s dreams, as an ex-felon with no employment history can do little but return to the streets. Is this, then, society’s fault as I argued earlier? Not exactly. Aileen gives up and chooses to return to her former ways, but it can be argued that the diminished community spirit of America and the largely market-based alliances that pass for interaction so isolate its members that it becomes all to easy to slip away into loneliness, depression, and depravity. Aileen experiences first hand how it is a rare thing indeed to receive help that isn’t tied to sanctimonious judgment.

Is Aileen, then, a man-hating lesbian and little more than America’s “first female serial killer?” That might be a convenient marketing tool, but still overly dismissive and cruel. The beauty of the film is that it is not exploitive, nor is it an apology for the actions of a sick woman. No one on earth would want to spend five minutes in Aileen’s company, and even fewer would block her execution. She shows no mercy to those she kills, and in one scene shoots a man who wasn’t soliciting sex at all, but rather wanted to help her with her problems. The film, much like Dead Man Walking, demonstrates that while we can understand to a certain extent (and confront our own need for violent retribution), we must be reminded of the crimes in all of their grisly detail. Aileen later claimed that she killed in self-defense, but only one of the murders fits this description. We watch Aileen butcher her clients without apology, steal their wallets, and drive away with their cars. Had the director cut away before the deaths, it could be argued that she was helping to exonerate Aileen. Oh, she’s guilty all right, but where does that leave us?

So we come full circle. I firmly believe that director Patty Jenkins is using Aileen as a stand-in for all those who commit acts of horror because they have long ago strayed from conventional means of achievement. Some people are rotten, deserve to die, and should never be the objects of our sympathy. But is the answer, as so many claim, to merely send them to the death house? Because the idea of deterrence long ago left the conversation, what we now have is a world where we desperately want to separate the good from the bad, giving tax cuts to those who play ball and the electric chair to those who do not. We have cells full of Aileens — people who have made terrible choices, leading lives of illness and rage — but is our only option this assembly line of death? Some would argue that even in a perfect society, an Aileen or two might arise (and I agree), but we are guaranteed generations of Aileens if we continue on our current course. Monster is flawed in the end, rushing its conclusion, and sometimes coming off as a TV drama, but I found more to embrace than I did criticize.

There is an inevitability about it that reduces the few moments of joy to a fleeting sadness, which is just the right note. What else would we expect? Here is a woman who got pregnant at 13, was raped by a family friend, suffered beatings at the hands of her father, and discovered early on that sex was the only thing that anyone ever wanted from her. She was never the object of true love, never secured a mentor or a friend without sinister intentions, and her mind was left in a fixed state of adolescence, as education and intellectual growth were defined from the outset as irrelevant. She was, simply put, no different from an animal; caged by circumstance, brutalized, and left to fend for herself. Again, many people with similar upbringings do not commit murder, but how many of that lot actually rise from their circumstances? Is the fact that someone with that life didn’t kill, but rather wasted away in poverty and neglect somehow a success story? Is that how low we have set the bar?

Monster states — these people exist, live as they do, and what are we to do about them? No solutions are offered, which is as it should be as it is a dilemma without an easy answer. And yet, it is obvious that lock-up and death row are not pulling us forward, which is perhaps as political as the film gets. If all we get out of the film is that Aileen was the devil incarnate, then we’ve done little but pat ourselves on the back while believing that we’ve made the right choices in life. At one point Aileen rationalizes her crimes by using the old chestnut, “the whole world is about killing.” Like Charlie Chaplin said at the end of Monsieur Verdoux, “One death a criminal, millions a hero. Numbers sanctify.” Slap on a uniform and channel the rage against an acceptable enemy and Aileen would be attending a White House ceremony. Fine, that’s a cheap excuse, but it is hard to define the act of killing as absolutely immoral if we make exceptions at the behest of oil companies. That is why, despite our intentions, our laws are often schizophrenic and too often an obvious product of our historical lust to protect capital. A bit of Marxism 101, but it can’t be so easily dismissed.

I doubt that Monster warrants such an extended analysis (or self-indulgent rambling, depending on your view), but if cinema is to maintain its role as the most powerful of art forms, each film must be subjected to an exhaustive review. Outside of relevance, Monster rises above some of its more conventional turns by presenting Charlize Theron in the performance of the year. And as others have said, it is much more than a beautiful woman slumming for awards. Watch her eyes and body language; she is never caught acting.

Dismiss the Method if you must, but it stands to reason that Theron, who as a young woman watched her mother kill her abusive father, was able to channel the pain and confusion of those days into Aileen. We believe at every step that Theron’s character is reacting, and we can see into her diseased mind, fumbling for solutions when none seem to exist. She is magnificent and always rises above the material. But those final lines stay with me, haunting my ability to toss the film into the “average” bin. Without those words, I might have recommended the film for Theron alone, but with them, I am forced to assess all that came before and wonder about intentions. As such, it is a worthy effort and yes, I’m going to think about it just a little bit longer.