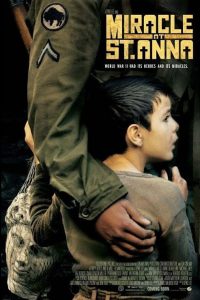

For all his talk of righting past wrongs, holding power accountable, and shedding light on Americas shameful, bigoted history, all Spike Lee has ever really wanted is an Oscar. He tried the bio-pic route with Malcolm X, pushed ever-closer with the documentary 4 Little Girls, and now, at long last, has gone to the mat with a traditional, hokey war picture. And not just any war picture, mind you, but one with all the trimmings: square-jawed Buffalo Soldiers for that racial broth, hearty helpings of sinister Nazis for flavor, a cute little urchin for that powerful kick, and a final blast of spirituality to hold it all together. Its the soup hes been waiting to make his entire career, and while the screenplay may have first appeared to Spike in a delightful, career-capping dream, its realization is more the stuff of nightmares. In sum, Miracle at St. Anna is the worst film Lee has ever made (with apologies to Girl 6); a bombastic, blow to the head misfire that not only regurgitates clichs with the fury of a fevered bulimic, but one that asphyxiates the audience for almost three hours of unendurable hokum. There isnt a single interesting idea in this movie save the obvious turn that racism is so very, very wrong, which at this late date is sort of like lecturing your retarded kid for not keeping his goddamn mouth shut at the grocery store. And yet, Lee believes hes cracking the case for the first time, forgetting that most of America has moved on.

Yes, this is just the sort of self-important history lesson that features the obligatory diner scene, where a group of black men (the soldiers during basic training) intrude on a segregated eatery in the Deep South, only to be met with the sort of restaurateur who foams at the mouth, pulls out a pistol, and even winks at the stock wide-eyed child with words akin to, Thats how we treat savages, boy. Some may feign shock (I heard a few gasps among our blue-haired crowd), but in reality, this resonates with modern audiences about as much as watching people travel by horseback. The yawns continue whenever a white person appears on screen, as to a man, they are frenzied, uniformly dreary bigots; as unchanging in their hatred as the tide that whips the shore. Fair enough, one might say: after decades of minstrel shows passing as black participation, its sweet revenge to watch the pasty actors take it on the chin for once. Still, this is to argue that caricature and bad writing are acceptable so long as an aggrieved party is fulfilling the duties of mediocrity. And yes, it is the most egregious form of poor penmanship, for it substitutes mere representation for depth, speechifying for nuance and growth. Sure, the whites of St. Anna are preposterous clowns, but the blacks fare little better, using their screen time to badger the audience into a numbing stupor. For whenever the bullets stop flying, and a few black soldiers retreat to a quiet cove, they speak not as men in war actually do, but as if auditioning for chairman of the NAACP.

A great film can, of course, be made from this subject matter, but Lee — hammering, grinding, overwrought to his core — is not the man to do it. Hes all agenda and score-settling, not the sort for enduring cinema. Hes like Stanley Kramer, only black and without real talent. What makes his tired humping from the pulpit so exhausting, however, has little to do with race or its centrality to the American narrative. In this context, with some of the years most appalling performances, any nobility of purpose is swallowed alive by scenes, characters, and dialogue ill-suited for the cutting room floor of a post-war B movie. As our group of warriors muck around the Italian countryside on a mission not even they understand, white commanding officers treat their black units like indentured servants, overweight man-children exhibit aw-shucks innocence, puckish kiddos inspire faith and hope, and Dago families come together to fulfill every last stereotype of their swarthy lot. And before you know it, theres a-beautiful a-woman who a-knocks a-you out with her titties (flashed not once, but twice) and who herself is a racist for fucking the lighter-skinned black dude rather than the darker guy who pines from afar. In a shocking turn, the two men engage in a fistfight over this very woman, who is quickly shot down like a dog for being as bad as any other white person. It helps matters that shes murdered with her beloved papa, the crusty patriarch who exudes central casting right down to his scraggly facial hair.

Above all, though, Miracle at St. Anna is a film undone by its jaw-dropping bookends, which attempt to mimic Saving Private Ryan in their poignancy, but instead send audiences into unintentional hysterics. The whole murder mystery scenario (why did Hector shoot that dude at the post office in 1983?) is insanely obvious throughout, never more so than when we see the Italian resistance fighter who, like, looks exactly like the murder victim from the opening scene, thereby undermining the alleged drama of the eventual betrayal. Yes, hes a turncoat, and Hector apparently has the presence of mind to not only recognize the bastard from forty years before, but gun him down without hesitation using the Luger pistol hes kept at work, apparently for just such an occasion. I suppose the excuse could be made that hes defending himself against a possible robbery, though I doubt theres ever been such a holdup at an American post office. Certainly not in the stamps only queue. Its the first of many groan-worthy contrivances that drown the film in its own idiocy, though before we can catch our breath, a newspaper is thrown out of a window in Rome, only to land (still folded) on the table of a man who turns out to be the young child we come to know. The papers headline, that the head of a famous Italian statue has been found in New York and had been held all these years by a Word War II veteran now being charged with murder, is exactly what this Italian needs to see, as it forces him to buy the head, sneak it down to the Caribbean, where he can sit with it on the beach as Hector, now an old man, comes along to weep and hug his old buddy from the war. But thats later. Much, much later. At least four hours by my throbbing ass cheeks.

No, lets stay with that final scene. Hector is out on bail, and appears surprised that he is in this tropical paradise. He did go to the airport and catch a plane, right? Someone brought him here, no? His lawyer told him a man of means was putting up bail (in cash), but we cut from that scene directly to the beach, so we dont know why the fuck Hector is so baffled. Immediately, a queer-looking gentleman is before him, speaking in stilted tones, and asking Hector to look over yonder at the figure sitting alone with a marble head. Did I mention that the guide introduced the stranger as the very guy who invented seat belts? You see, because the Buffalo Soldiers (primarily Train, the fat, goofy fella) helped this lad, he was allowed to survive and eventually create a product that saved millions. So that sacrifice wasnt in vain! Their reunion on the sand is filled with tears and joy, though the closing credits come before we can make sense of what the hell just transpired. All I know is, the kid, Angelo, had an imaginary friend in his village who wasnt imaginary, but the ghost of a murdered child who met his fate at the Church of St. Anna, where dozens were massacred by the worlds most evil Nazi. He even blew away a priest! So Angelo is the miracle of the title because he lived to make millions and keep his fellow man from flying through windshields. Spike apparently thought this claptrap was the proper way to honor the black regiments of the good war, but I suspect audiences will be laughing too much to pursue further reading on the subject.

Other absurdities abound, from Hector being awarded a Purple Heart on the spot (who knew?) to Tim Boyle, cub reporter, shouting like a wounded bear in the courtroom after Hectors dismissal: Whos the Sleeping Man! WHOS THE SLEEPING MAN! If you must know, the Sleeping Man is an Italian mountain that looks like, well, a sleeping man, which is replicated as a choking soldier is silhouetted next to that very image. Oh yeah, and Hectors murder weapon? A gift from a regretful Nazi, who hands it to Hector as hes leaving the village. Defend yourself, he says, in an accent suspiciously Southern Californian or something, but decidedly not German. History tells us many outrageously true tales to be sure, but I do not know of a single one where a Nazi willingly handed a Negro a gun in the heat of battle. Especially a Negro who has just spent the last fifteen minutes killing two dozen of his fellow infantrymen. And since when did the army, even with a draft in place, accept obese simpletons whose credulity allowed them to believe in magic statues? Maybe Bushs army, but not the goddamn greatest generation, Ill tell you that. And please, before Spike shoots another foot of film, would someone kill Terence Blanchard? Its bad enough that Lee insists on using music in every single scene, but when its this overbearing and manipulative, its all one can do to remain seated (or sane). The Nazis even get their own sinister drum beat, proving that melodrama is alive and well and living in Brooklyn.

Its all a colossal waste, and surely one of the biggest disappointments of the year. Instead of fire and grit, Lee has tipped his cap to the old school, contradicting a lifetime of revolutionary excess. Does he mean it? Is he fishing for compliments, respect, and awards? As stated, I do believe Lee wants to be the first black man to take home a Best Director honor, but at the same time, his heart and soul are in this film as much as Do the Right Thing. And yet, Lee has never before been this corny, labored, and insultingly obvious, even over a career of ham-fisted imagery. He wants to play the wise professor, plucking the obscure from mothballs and giving it new life, yet his method is to make his heroes as bland and interchangeable as those he derides. And by insisting on opening and closing scenes away from the sting of battle, he admits to a weakness in the story he himself has chosen, as it fails to trust an audience to make up its own mind about the past. And as it grinds down to its final moments, we remember nothing, care for even less, and discard the characters into the same bin as a hundred other rote failures. Yes, black Americans fought and died in that last, most righteous cause, but rather that elevate their sacrifice, Miracle at St. Anna insults, minimizes, and wastes every possible opportunity. One wonders if the subject will ever again be up for reconsideration.