The malleability of behavior is a central theme to Martha Marcy May Marlene, in that moving the goalposts to manipulate expectations can have far-reaching effects that are impossible to alter. Martha has joined a cult in rural New York, and after a couple of years, decides to escape to live with her sister. She is not the introspective sort, but is unable or unwilling to reflect upon her experience and thus rejoin the land of the living. Light on background details, the audience is left to fill in the gaps with their own perceptions, allowing the viewer to become inserted in the action. This pays off as MMMM becomes a psychological thriller of sorts by becoming increasingly immersed in dread. The woman Martha was is now gone; anyone who submits to a profound life-changing experience is no more afterwards, and there is no going back.

The structure is filled with flashbacks and present day interwoven improbably, the division between the two left intentionally murky. Just as we have difficulty at times telling where we are temporally (with the cult or her freedom after), so does Martha. Her mind is perpetually in the clouds, and disturbingly comfortable with this gray area. When leaving the cult, she is pursued by her ‘family’, one even cornering her at a diner before oddly leaving her alone. This is just the first of many physicial suggestions that she is still a prisoner; most such signals are psychological, and run deeper than Martha is able to articulate. By swimming naked, asking strange questions, jumping into her sister’s bed while she is having sex, and disrupting any social gathering, it is clear she no longer fits into normal society. As is made clear, however, there is no ‘normal’ anymore. One would expect Martha to be grateful for having a place to stay, but her flat affect belies some regret.

Her experience in that place was frightening, but also one of community, albeit deeply incestuous. At the head of the cult is Patrick, portrayed by the formidable John Hawkes, as a manipulative patriarch. He is able to convey simultaneous tenderness and threat, playing upon a person’s guilt and inducing humiliation, all while making his words seem a kindness. The part is a thin one, and while Hawkes makes the most of it, it seems a lost opportunity. Still, Patrick is not meant to be messianic, just charismatic and scary in equal measure. I suppose if he were a more magnetic presence, Martha would have been sucked into the cult rather than simply joining it out of something between loneliness and having nothing better to do. We never learn much about the cult, why they are there, if there is some rebellion against the outside world or government, or anything other than group sex and aimless crimes. That is all immaterial, really; Martha is the focus here, and her fear and attraction for this dangerous group drives what story there is. The cult has not given up their search for Martha, a woman so renamed Marcy May, and her sister is given no indication of what is to come. Marcy May has no reason to warn her, so alien are they to her present state; we are made to feel as helpless as she seems to be to resist.

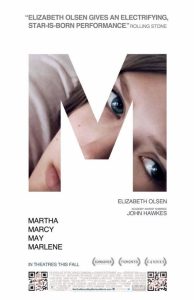

While there is little plot to speak of, MMMM thrives on the eponymous character rather than any greater point. Elizabeth Olsen portrays with muted anger and numb desperation a person broken at the core, with nothing of substance to replace what was lost. The vacuum at the center of her previous personality was swayed by Patrick and the other members of the cult that dug in deep to adopt her into their family. She was all too willing to be filled, so to speak. Martha is described as being intelligent, and the point is well taken that mental ability does not make one less susceptible to influence. If her inarticulate present or lack of reflection is any indication, she had little constitution to begin with. Nature may abhor a vacuum, but parasitic individuals with charisma positively adore them.