Luis Bunuel is one of cinema’s most reassuring directors, if only because he confirms time and time again the essential absurdity of existence. Whereas some might seek the mother’s milk of closure and affirmation, I am warmed — rocked to sleep, if you will — by ambiguity and cynical despair. If a film ends happily or with even a hint of consolation, I am kicked into a cycle of crippling depression. With Bunuel and his delightfully vicious view of mankind, I am lulled into a hellish state of bliss, cackling hyena-like all the way down.

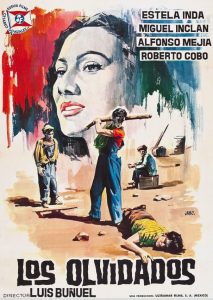

And while Bunuel is not always at the top of his game, he never fails to remind me of why sublime worship is a command I can in good conscience follow. Los Olvidados, his near-masterpiece from 1950, has so many things going for it that I fear my enthusiasm will engender a childish babble rather than anything resembling a coherent argument. After all, if Bunuel is not the pinnacle of Ruthlessness, then surely the word has no meaning.

The film in question might not be his best (I’m partial to the wickedness of That Obscure Object of Desire), but in terms of cruelty and the unflinching avoidance of sentimentality, it best typifies why Bunuel remains synonymous with enlightened filmmaking. Here we have the story of street children (the title translates to “The Young and the Damned”) that, in lesser hands, would be cutesy and trite, but under Bunuel’s steady direction, is an open-ended portrait of hopelessness and misery, tempered only by a sense of humor so nasty that some might mistake it for sadism.

Bunuel’s masterstroke is that he refuses to give us anyone to root for, and to a man (and woman), the characters are selfish, vain, mean-spirited, and yes, damned. Their lives end unhappily, but in addition to the circumstances that bring about their pain, there remains a sense that even in ideal circumstances, these people would still be rotten.

Take Pedro, a hero of sorts, who tries to rise above his lot in life, yet remains sad and depraved, as if doing the right thing is a sucker’s choice. He’s a miserable little snot — out at all hours and indifferent to his mother’s concerns — yet tries to reform by securing an adult’s trust at a boy’s home that in reality is nothing more than a slave labor camp. The money he is given as a “test” is stolen, which will teach the brat to think he can ever come out ahead.

Again, we might sympathize with the boy, but we remember earlier when he participated in the savage beating of a blind man. And what about that blind man? In a lesser, more Americanized picture, the sightless gentleman would be a fountain of wisdom; a sympathetic stranger who would double as moral guardian for the children of the streets. Instead, Don Carmelo is a nasty old coot; a pedophilic prick who begs for help, yet deserves little more than a hard push into traffic. Moreover, Carmelo enslaves a young child, Ojitos, who has been abandoned by his father. The minute we might open our hearts, Bunuel punishes us for even entertaining the thought.

The vilest beast of all is Jaibo, a murderous punk who bludgeons the only kid in the area who is working an honest job, and later ends Pedro’s pathetic life. Jaibo himself is shot down like a dog, but not before he shamelessly flirts with Pedro’s mother. In a wonderful, unexpected turn, Pedro’s mother fucks the nasty youth, which seems unmotivated until we realize that in Bunuel’s universe, there is literally no redemption offered. Hell, it’s impossible to even conceive of such a concept. Pedro’s mother is made even less sympathetic by the fact that she openly hates her son because he is the product of rape.

Given her loose morals, however, we have a hard time believing that she’d resist anyone. The mother’s status as a whore is coupled with the young tart Meche, who uses her camera time to rub milk on her thighs and prepare for her future life as a harlot and/or rape victim. This is Mexico City, partner; an attractive young girl has no option save the brothel. Even the boys aren’t safe, as whenever an adult is present, the not-so-innocent are being lured into cars for what promises to be even more sexual exploitation.

And so we come to the conclusion, a fine affair where Pedro’s mother comes looking for her child, and does not notice that he is being carted away to the city dump by those who found the murdered boy and don’t want to be blamed. The body is rolled down a massive pile of garbage, where it comes to rest in a bed of indifference and apathy. Soon, the crows and bugs will pick away at the decaying flesh, and it will be like the boy never existed at all. For all we know, there could be hundreds of such bodies in the dump, left there by uncaring parents, drunken guardians, and heartless killers covering up their foul deeds. In the end, society itself doesn’t care, the audience doesn’t care, and the world continues to turns its collective back on the plight of the uneducated, the poor, and the deviant.

As Carmelo shouts when Jaibo is shot down, “One less! One less!” Faceless, undesirable, and better off dead — so goes the world, and so goes the universal attitude towards the Other. Nevertheless, I do not wish to leave you depressed and doubtful. Well, actually I do, but on my terms. Take pleasure in the feeling, my friends, as the world, for all of its heartache and pain, managed to give us the likes of Luis Bunuel — misanthrope, cynic, atheist……savior!