For a blueprint on why the HIV pandemic has shown such extraordinary resilience in southern Africa, look no further than Life, Above All. This beautifully shot and expertly crafted film ticks off each of the layers of protection that a society should have to protect itself and shows each are badly in need of repair. The point of view is from a young girl living in a township on the edge of a city, and she is inundated by rumor, ignorance, death, and temptation swirling in a melange that renders her schooling an easily forgotten distraction. On a deeper level, Life, Above All explores the war between fearful superstition and cool fact, and their proxies against this backdrop. It strikes a careful balance between sentimentality and detached regard, avoiding the trap of tragedy porn. The subject is a devastatingly tragic one, but it suggests a way through by embracing unvarnished honesty. There is no other way to deal with adversity of any kind other than head-on, and it can be said that AIDS has been less damaging to Africa than the ignorance that nurtures it.

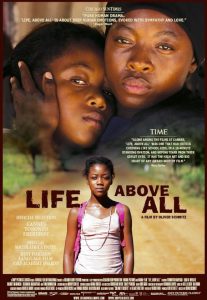

Khomotso Manyaka leads a talented cast as Chanda, a young girl who is strong enough to face buying a coffin for her dead little sister. In the first of many unsettling images, she surveys a room with an unreasonably good selection of oblong boxes just the right size for an infant. She is sharp, and able to discern a growing sense of loss in her mother beyond mourning. She is sick, and her husband is far sicker; he whiles his time away in the shebeen drinking away whatever money he can steal from his wife while lamenting that she poisoned them all. The community is filled with suspicion and mutual loathing, treading heavily upon the empty cliche of how a village raises a child. They can see the illness, and word spreads wildly about the curse. Harriet Lenabe gives a striking performance as a neighbor who truly means well while fueling the rumors in an attempt to manage them. Her magnetic presence suggests great skill at manipulating public opinion.

The drama rests on how Chanda copes with the coming realization that her mother is dying, and her arc is in realizing the futility of comfortable delusion. If you work in a South African hospital, you will be astounded that nobody dies of AIDS. Pneumonia, tuberculosis, trauma, diarrhea, even ‘old age’ in people as young as fifty are the only causes. Everybody knows, and in Life, Above All, the word remains just under the tongue of the community. They know, but ignore, and refuse to face the problem tearing their world to pieces. The fear is palpable, and effectively blocks prevention education while casting a protective barrier behind which superstition and rumor run wildly. This is why people believe sex with virgins or small children cure HIV or that condoms spread disease. In one remarkable scene, Chanda accompanies her mother to a doctor who is famous for curing ‘the bug’. She surveys his certificates, asking him “Are these your degrees?” As he responds proudly, she notes balefully that they are all sales awards – not a degree in sight. Even in fear of death there is a robust market. Chanda’s mother attends a sangoma (traditional healer) who puts on a show of curing her, all the more repulsive for her having paid for it. Every person who reaches a clinic or hospital has been to one of these thieves first, often many times before their first trip to an actual doctor.

Nothing about the structure in this society responds properly to the crisis. Family members are made to hate and fear one another; the community treats those who may be infected with contempt or even murder; the health care system is pushed beyond the breaking point; elected officials fail to acknowledge the epidemic or actively feed it with their own inspired levels of ignorance. Life, Above All focuses most of all on the intimate moments that fall victim as friends and loved ones stab each other in the back in public while apologizing in private. The shame is buried so deeply that it covers everything in sight.

And so it goes that the response to AIDS begins where any proper response to a catastrophe must – at home. An economic disaster must be remedied one saved business and consumer at a time; a political failure is fixed voter by voter; ruined land is repaired acre by acre. Chanda responds to the hatred of her community with her own house, making it one of disease and compassion. The response by one of her family members is heart wrenching, and transcends the drama into a much larger point. Some may see this as unrealistically hopeful, but only if taken literally – this is from the point of view of a young and somewhat idealistic girl who has learned from her mistakes, starting with understanding she has made them. This is a work of emotional resonance that is involving and universal. South Africa may have responded poorly to its challenge, but every nation has dealt feebly with the cataclysms in their midst, and the blame rests on every member of society who is comforted by their delusions.