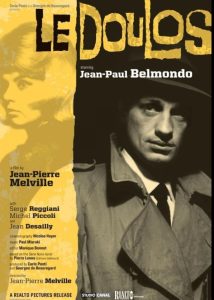

Though Melville’s later films would prove to be his most enduring classics with existential themes that transcend genre conventions, this early work is cracking entertainment that is deceptively simple, masterfully constructed, and a beautifully shot exercise. The love of his life is the milieu of the criminal underworld, stripped of romanticism and peopled with doomed characters for whom fatalism is a secular religion. The nouvelle vague had already struck the world of cinema with the thunderbolt that was Breathless, and its star, Jean-Paul Belmondo, was already an international sensation. His effortless charisma is used here to play with the audiences’ expectations with a deeply complicated character at the center of Le Doulos.

The term “Doulos” means that (the informer), but also signifies a police informant. A quote opens the film, one Melville borrows from Louis-Ferdinand Celine: “One must choose: to lie or to die.” This is the credo of the criminal, unless they choose to wear the hat of the informer when cornered. In a shadowy world where the only words spoken are half-truths or lies, one cannot trust the information given to them. The viewer would do well to heed this, as the events that are about to unfold do not mean what we would expect.

In the opening shot, Maurice Faugel walks purposefully along, melting in and out of the shadows. He is a dour character, beaten down by a recent stint in prison, and he is on his way to the house of a trusted friend for a job to get back on his feet. The structure would appear to be the standard setup for a crime thriller, as the hoods assemble, plan the caper, and either get away or get caught in the aftermath. These assumptions are shattered abruptly as Faugel commits an act of betrayal and so he is on the run. We will later find out the reasons for his decision, but for now all we have to guide us is his mood and the nuance of each inflection and gesture between the men.

With this sharp right angle, Le Doulos becomes a study in behavior, and a guessing game of who the informer will be. Faugel reconnects with his girlfriend, and then his right-hand man, the secretive Silien, as played by Belmondo. His performance is an internal one, of a character who is well-known and respected in the underworld, but is suspected of being a stoolie to a cop who is an old friend. His speech is friendly but compact, containing little information except that which counts to those who need to know. Upon a repeat viewing, his every gesture is the only language of value to Silien, and is the only hint as to his motives. He is quiet, but capable of brutal violence, as shown in a shocking moment that leaves little doubt of his malevolent intentions. Or does it?

As the story progresses, a heist is arranged, but is thwarted by the “doulos” as the cops arrive, and it is not entirely clear if Silien is involved. He could be either a bystander avoiding the chaos until he can retire, or he could be playing chess. As characters are introduced, the shape of the plot becomes better defined, but the truth is always held just out of reach. The key to why the pieces fall where they do is in the past with Faugel, Silien, and other important characters like Nuttechio (played by the immortal Michel Piccoli), Fabienne (Silien’s former lover), and Therese, who Silien recognizes with a fleeting but knowing look.

What happened years prior is what guides their hands now, and ultimately it is a question of fate. When everyone plays the part that is required of them, then there is no real freedom of action. The pieces on the board rarely have a moment to breathe, to betray a human moment, except one. Silien pauses to greet a horse in his stable, a magnificent animal that symbolizes a moment of rest, and part of his hopes for the future in his retirement in the French countryside. Then, it is back to the game, and each individual faces their destiny with grim determination.

Melville’s trademark gritty setting and muted performances create a pessimistic addition to the noir genre, but Le Doulos is a supremely engaging work of intricate beauty. Belmondo’s alluring Silien is by the same turns callous and allegiant, and he is never less than fascinating to watch. Melville’s eye for austere elegance is without peer, and though Le Doulos is somewhat more straightforward than his later achievements, it is one of his most entertaining films.