“When men, even unknowingly are to meet one day, whatever may befall each, whatever their diverging paths, on the said day, they will inevitably come together in the red circle.”

When a great filmmaker reinvents cinema, perfects his technique, and begins to coast, what happens to his creative output? Does he crash into a heap or simply fade into history and irrelevance? Godard veered left and became involved in increasingly disconnected projects, Eastwood has been comfortably chasing mediocrity in the Oscar ghetto, and Coppola is still searching for the better part of his brain matter after Apocalypse Now fired a definitive slug through his magnificent dome. Then there are others who still find ways to reinvent themselves. Werner Herzog remains unpredictable and was never better while crafting Grizzly Man or Encounters at the End of the World; Robert Altman made one his best at the bitter end by using the creative process of A Prairie Home Companion to consider mortality.

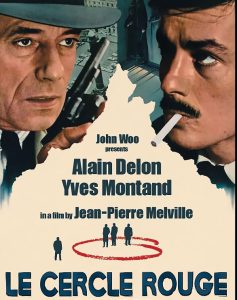

Jean-Pierre Melville, after playing an integral role in the French New Wave, created an entire mythos of the criminal underworld. The landmark Bob Le Flambeur through the cool perfection of Le Deuxiemme Souffle recast noir and established a stylistic world of men in trenchcoats following a code to a seemingly predetermined end. As his filmography came to a close, Melville stayed in this world (apart from his masterpiece, L’Armee Des Ombres), but appeared to become more philosophical about it. Like many of his contemporaries in French cinema, Melville was a fatalist, and the characters in his films reflected this belief. They have parts to play in a grand tragic comedy, and though there are individual decisions to be made, one cannot escape fate. The dancers take their steps in what appears to be a predestined choreography. The gray wolves of Melville’s shadows would seem to be able to evade such an end with lives lived outside of the norm and established rules, but such outsiders adhere to the least forgiving ideology of all. Cops have their duty, hoods have their code, and all have their destiny. What began in Le Samourai came to a resolute end in Le Cercle Rouge.

Corey is a veteran thief who has just been released from prison; before he exits the gates he is offered a diamond heist job by a guard. Vogel is another thief and killer who is on his way to prison, escorted by detective Mattei on board a train. He evades the detective and makes a desperate escape into the forest as winter descends upon the countryside. Both are aberrations from the natural order that will soon be corrected. There is a daring theft, a disturbance in the smooth ocean of daily life, but once the waves break, they return to their previous level.

You probably know where the story is going already, but as with any great story, it is in how it is told that our attention is seized. The players are among the best in the business, and watching skilled individuals doing a job well is the best entertainment possible. Corey and Vogel are played by Alain Delon and Gian Maria Volonte, adept men who work in silence, preferring to speak with their eyes when at all possible. Their paths cross and it is as if both were expecting to find the other; when Vogel crawls into the boot of his parked car, Corey registers no surprise. After all, he is on the run as well, after robbing his former employer for giving his ex a reason to betray him. Women do not have much of a place in this world apart from entertainment or disappointment. Masculine figures are all that matter in a world of sharp edges and fatal wounds.

So the hoods are on the run, and the accomplished Mattei is on their trail. Even when he knows full well they have escaped, a good cop knows a criminal will reveal themselves eventually. As his chief is careful to remind him, “All men are guilty. They are born innocent, but it doesn’t last.” He would know; the best policemen think like criminals, move in their circles, embrace their vices. There will be one more intersection for them all. Before we get there, there is a burglary, and it requires the services of a crack shot. In steps ex-cop Jansen, played with steely quiet by Yves Montand.

He is an alcoholic, introduced in an unsettling scene that is one of the most vivid episodes of delirium ever filmed. His sure hand may provide him with a moment of redemption; just as performing their tasks skillfully may redeem Corey and Vogel; just as capturing his quarry shall redeem Mattei. Risk and redemption, and the void beyond is a recurrent theme in Melville’s work. He understood that success does not justify itself – victory only lives in the moment, but there is always the failure of tomorrow waiting for you. This can be seen in the resigned look of Vogel and Corey; they regard one another with no fear, just caution. When Vogel meets Corey, he holds a gun on him until intentions are made clear.

Corey tosses him a pack of cigarettes, followed by a lighter, requiring Vogel to put away the gun. Mattei clearly shows no gusto for capturing his prey. No self-righteous speeches about right and wrong, since those terms are interchangeable depending on your perspective. He does not do the right thing, just his thing. This can be seen in the costuming for the characters, which are identical – cops and criminals look alike, act alike, speak alike; and if times are tough, they exchange their roles as outlaws turn informer and cops skim off the top.

The centerpiece of Le Cercle Rouge, as with all heist films, is the job itself. Strangely enough, it occurs with little fanfare, no expository dialogue about the setup, and little tension during the job. It would seem lazy, but Melville always has another agenda in play. Almost before the theft is completed, it seems clear that this will make no difference in the outcome, and any sense of triumph should remain fleeting. This is especially true for Montand’s character – an alcoholic ex-cop fresh off his DT’s would be ripe for tragedy. It is up to him to place a shot perfectly or they would all be trapped. After he readies his rifle, bolted into a tripod, he makes a snap decision that sucks the oxygen out of the room. He reclaims his soul – in the practical world this means validation of his craft and nothing more – in a temporary fashion, but that is good enough.

As with all of Melville’s work, the shots are crisp, the details immaculate, every word, gesture and motion efficient almost to a fault. If not for the extraordinary craft, one could accuse the director of egregious exercises in style. Even if so, this is a philosophical work in the guise of a genre film. Melville was no Buddhist, and the opening quote does not reflect a sense of destiny as a vague spiritual force, but rather the inevitability borne of human nature. These are the ants to which Harry Lime referred in the ferris wheel, and they would not begrudge the indifference of a distant audience. There is indulgence in the form of entertainment, whiskey, perhaps an errant rose or time with a woman, but none of these players are under any illusion that such things are granted. These things, joy and pain, all pass and so we meet our end.