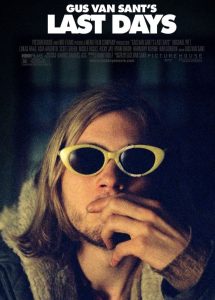

As with Gerry and Elephant, Gus Van Sant’s Last Days is a tale of creeping death; an exercise in minimalism so bereft of conventional cues and triggers that immediate rejection seems the only appropriate response. Simply put, there is no story to speak of, characters come and go with relative anonymity, and overall, it has less spoken dialogue than any film in recent memory. Meandering, maddening, pretentious, and pompous in the extreme, it has all the makings of a hateful, poisonous experience at the movies, yet it remained captivating from beginning to end. It is, quite simply, one of the most realistic representations of despair I have ever seen. We have come to expect fireworks, melodramatic turns, and endless monologues about the slings and arrows of life as characters meet their end, as if facing mortality transformed the inarticulate and the ordinary into cocksure poets.

Perhaps it comforts the afflicted or soon-to-be-afflicted to believe that if overcome with depression, or addiction, or disease, we will stand firm, clear our throats, and leave our loved ones with closure and understanding. Here, there is only confusion and stubborn, painful banality. The truth is, as many of us stare into the abyss, we are so paralyzed with fear that it’s enough to adhere to routine. The central figure of Last Days (named Blake, but only for legal reasons, as it’s obviously Kurt Cobain) is hardly typical in that he’s blitzed on heroin, but rather than go out in a blaze of glory, he wanders about, doing little but mumble, pass out, and occasionally strum a guitar. Removed from the only thing that gives him strength — his music — he is utterly helpless and alone.

This is not a biography of Cobain, nor should it be read as a tribute. Taken literally, what we witness reduces Cobain to his essence: broken, addicted, and so withdrawn into himself that it understates the case to call him narcissistic. I’d say he was a jerk, but that would be granting him agency, and he appears to have long ago given up any effort whatsoever. His responses to the few people who attempt conversation are rote and uninteresting; not in terms of the film, but rather in the context of normal human interaction.

One of the best scenes, which involves a Yellow Pages salesman, is both hilarious and sad, primarily because we are aghast at the ad rep’s relentless pursuit of the sale, while we also notice that Blake is unable to offer anything that isn’t a tired cliché. In many ways, the salesman is afflicted with the same illness as Blake, only he’s deemed respectable because he wears a suit to work. As far-gone as Blake is, it is worth noting that his behavior reveals how pointless most human speech has become. If this is what we say to each other, why not mutter incoherently under our breath? The same point is made when two Mormon missionaries pay a visit, as their speech is so robotic and stale that you can practically see the strings. A cheap shot against an obvious target? Perhaps, although it’s so understated that we’re not sure if Van Sant meant for us to laugh.

And so we beat on, waiting patiently as Blake takes a walk in the woods, fixes macaroni and cheese, and puts on a negligee. He answers the phone, remains silent, and hangs up. He is briefly pursued by a private investigator (said to have been hired by you-know-who), escapes into the woods once more, and pretends to listen to a friend who stops by. He plays with a gun, puts on a coat, and lays on the floor while music videos play nearby.

There’s a brief walk into town, where he is accosted by a stoned loser who appears to be talking about dentures or something, and then more lounging, mumbling, and changing shirts. It’s tedious to be sure, but I can think of no other way to tell this story authentically, especially when the tabloid junkie in all of us wants to see the slaps, the late-night arguments, and the old standby where Blake pulls out his equipment and laces up for a bout with the needle. Seeking drama, craving action, it seems arrogant for any filmmaker to deny us expected pleasures of peeking behind the curtain of celebrity. Instead, we see a pathetic shell of a man who, from all appearances, could not possibly be the sort of person who could seduce millions and capture fame with apparent ease. This is the plumber or the cable guy, not a rock star.

The most powerful scene of the film (even if expected) involves Blake coming to life for the first and only time as he plays a tune from beginning to end. Camped out in a lonely corner with just an acoustic guitar, Blake starts softly and slowly builds the intensity until it threatens to flood the room. At once we realize that Blake has nothing else holding him together, but as he eventually commits suicide, it is clear that not even his one and only love is enough to save him. An essential truth about artists seems to be their inability to live regularly — not without fortune and the paparazzi per se — but rather off the stage, or outside the environment where creation occurs. Such people cannot work, or take calls, or sit around and just talk; they are so restless and driven to create that idle time is a moment where they must face their glaring weaknesses beyond their gifts.

That is not to romanticize these folks, for surely the untalented and deluded have similar obsessions. Cobain’s contributions to culture and music are surely debatable, but that’s not the point here. Cobain, rightly or wrongly, saw his music as his only salvation, and that’s what Van Sant seeks to explore. And yet, this is not a film about music, or the musician’s lifestyle (again, as attractive as that would be for so many of us); but simply a man — a silly, boring, self-destructive man to be sure, but must we only commit to celluloid the adventures of the heroic?

The film’s conclusion contains a painful, glaring flaw, but it’s not enough to kill the picture. Having dedicated himself to stark, unvarnished realism throughout, Van Sant resorts to a cheap “spiritual” dimension that simply does not belong, and not completely for the expected religious objections. The scene makes literal the lyrics in Blake’s final song — “It’s a long, painful journey from death to birth” — when it was enough for us to imagine. True, Blake and Cobain sought an escape from life, but to grant this man a world beyond is to miss the point of what has come before. Instead, we should have been left with Blake’s corpse, as how else to wrap up the final moments of pain than with permanent isolation? And why return to those bizarre roommates; those slackers and bums who shared Blake’s moldy, dark retreat, yet existed as if inhabiting another planet? This was Blake’s tale, and when he died, so did the reason for the film.

Missteps aside, this is a remarkable film — more so for shocking the hell out of my expectations. Van Sant’s trilogy inhabits a world of experimentation and daring, and again I reiterate that I really have no business embracing them. As open as these films are to mockery and eye-rolling disgust, they work because they declare their intentions from the outset and stay true to their vision.

There’s no wiggle room here; you’ll either accept them with genuine excitement, or loathe their very existence. Both are understandable, and no one should be judged for a response exactly opposite to my own. But Van Sant proved himself an artist with these films, shifting time, repeating scenes (only from different points of view), and refusing to play by the rules Hollywood has set for “success.” Static shots, dialogue that goes nowhere, characters walking and lounging without consequence — these are normally the elements of a nightmare. Here, they are in fact that very thing, only not for us. At least not yet. But our time will come.