When the dream is within a dream, it raises the question of where it all ends and reality begins. In our lives, the only reality is the moment about to pass, and all else is constructed of memory. That memory is faulty, riddled with inconsistencies and gaping holes that are altered and shaded according to our wishes and neurological imperfections. Christopher Nolan explored this notion in Memento, in which a man with retrograde amnesia represented an extreme of what everyone experiences as a memory that will simply fabricate that which it cannot remember to iron over gaps in one’s retention. This is no small issue as our identity, in fact our entire reality is constructed of what we thought happened, what we perceived in others, and much of it is false and cannot be trusted. This mind-bending concept is pushed off the ledge entirely for Inception, in which dreams are layered in a way that stretches the definition of reality well beyond the breaking point.

In the eye of our protagonist, nothing of what we see can be cast in stone as part of any real world, as it could be another dream state. Everything and nothing is explained, and the construction of this fabrication is tight, Byzantine, and consistent only with its own inner logic. Inception is every inch as good as you have heard, and has already been hailed as an instant classic. It will grow in estimation with time, however. Inception is a riot of psychological trickery and wallows in regret, loss, amnesia, pleasant fictions and bitter loss – the flora of our subconscious that grows and shifts with the speed of the living world. It will be a different film to each person who sees it, as your perception will be informed by your own experience and mental baggage. And since we are different people every moment of every day, it will be a different experience each time the individual watches it. Does this intrigue you? For me, I was utterly lost in the vagaries, and did not really care about emergence from it.

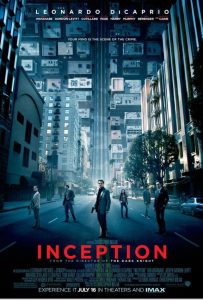

Cobb (Leonard DiCaprio) is a professional thief of dreams, armed with a Whatever Technology that enables him to enter another person’s dream and sniff out secrets. A conventional movie about this premise alone would be entertaining enough, but we are instead sent into a sort of heist plot where a team is assembled for a more complicated purpose. Rather than extraction, which involves finding something out from a person’s subconscious, Cobb is hired for inception, or the planting of an idea into another’s mind as if it were their own. If you have ever attempted to persuade a person in any regard, you know how difficult this is, as the mind rebels against an alien thought – unless they truly believe it was their own to begin with. Or if they are a gullible idiot – but nobody would bother invading that sort of mind. For this task, Cobb is working with his longtime partner Arthur, played by Jospeh Gordon-Levitt, whose natural acting style hits a cool and efficient stride that effortlessly moves between professional reserve and kicking ass. Eames (Tom Hardy) is a charismatic forger, here meaning an impersonator.

An architect (Ellen Page) must construct elaborate worlds in which the dream thieves must work, large enough to occupy extended sequences with details that will not betray the dream to the person who is being invaded. Saito (Ken Watanabe) hires these men and tags along for some reason as he has an interest in a corporation headed by the mark who is drugged and set for this dream sequence. The most interesting character is not there at all – Mal, played with unstable ferocity by Marion Cotillard, is Cobb’s wife. She betrays them all, every step of the way, because she is a subconscious projection by Cobb that has grown monstrous with time. The setup of this job is as intricate a maze as has ever been, and somehow Christopher Nolan keeps all the balls in the air with long and tricky setpieces that tie into simultaneous moments occurring on another plane of fantasy. As the team descends from one dream into the next, notice how the action is informed by the identity of the sleeper.

Rules are established for this world in scenes that are every bit as fun to watch as the execution of those rules. Since Batman Begins, Nolan has taken the rather laborious task of exposition as a challenge, and has risen to it. Who knew that a movie about Batman would become less interesting when Batman actually suits up to wreck shit? The best scenes consider why adopting an alternate persona is not only useful, but essential to inspiring hope in citizens and fear in their enemies. In Inception, these rules are many but intuitive to how the subconscious works. When Cobb is explaining to the architect how in a dream the person creates and perceives simultaneously, this seems innate, but you can also sense that this applies to the story proper.

After all, if one cannot tell where the dream ends and reality begins, is there a margin to this tale, or is this the protagonist’s creation that becomes more elaborate with time? Is this plot part of another inception? Even the cliche touches of the ‘one last job’ seems the hacky work of a mind asleep utilizing familiar touchstones. The characters have an otherworldly feel about them; all of their appearances are simple, blank face, hair slicked back, all movement is efficient and minimal, much like the supporting cast of our dreams. And in this layered chimera is the notion of inception; a parasitic idea that is not of our creation, that dominates the mind. The job within the film involves such a concept, but there are many others; chief among them the idea that Cobb is lost in a dream. The clues abound as to whether this is true, and the Macguffin nature of the job lends some perspective, but I suspect there is no real solution to the puzzle. The walls of this labyrinth will shift the next time you watch, so keep an open mind. One character utters the line “I need a guarantee!” The response is clear and murky at the same time, in keeping with the playful nature of the film.

Some reviews have complained of a lack of visual insanity, which is an idiotic notion. Unless inspired by shrooms or fever, typical dreams are populated by places and people we know, often with dull or familiar situations. Except that as the dream progresses, the laws of physics go out the window, rooms change shape, time speeds or slows, and things fall apart. Nolan captures this idea with extraordinary clarity. Inception is not meant to be a perfect film, just as The Dark Knight was not meant to be a conventional action film that can stand nitpicking about whether Harvey Dent’s face could actually look like that. These, like all of Nolan’s films, are a psychological playground of ideas that consider matters of individual identity, and how easily it can be warped. The visuals are striking and beautifully realized, and reflect the massive but generalized worlds that occur in the mind. Familiar, yet illogical, particularly in the remarkable scene where a city is folded. More important, though, is the emotional resonance within – our dreams are a thick soup of emotion that itself bends solid structures and darkens the skies. Cobb’s tortured psyche makes this a dangerous place filled with self-loathing, regret, and loss. The pleasing moments are there, but fleeting, and ultimately yield to the destructive power of desire.

Subject to variable rules of physics in a mind prepared for intrusion, the action scenes are unique and uniquely amazing. The hallway fight is as good as any I have seen. The sequences involving shitloads of bullets I could do without, since my sense of entertainment is inversely proportional to the number of bullets fired. Even so, in what would seem to be mindless action scenes, Nolan is able to inject some questions. In the chase through the streets of Mombasa, for example, Cobb’s ability to always be just one step ahead of the projectiles seems like the sort of thing that would work in a dream. Right down to squeezing through a tight set of walls. Enough of the particulars – rest assured you will be swept along.

Throughout this ride, Nolan holds the reins tightly. In a world where anything can happen, you have no reason to care about what happens, and this is the central problem with CGI-dominated films. Yet here, this malleable universe is similar to that within our own minds, and our ability to identify with it makes it all matter to us somehow. The potentially maddening idea of a dream within a dream can alienate an audience. And it would, if we did not have that experience before, and then found to our displeasure that some of it was substantial enough to populate what we thought were authentic memories. The unease is palpable, and the lack of a guarantee is satisfying and exasperating in equal measure. And this is the way it must be.