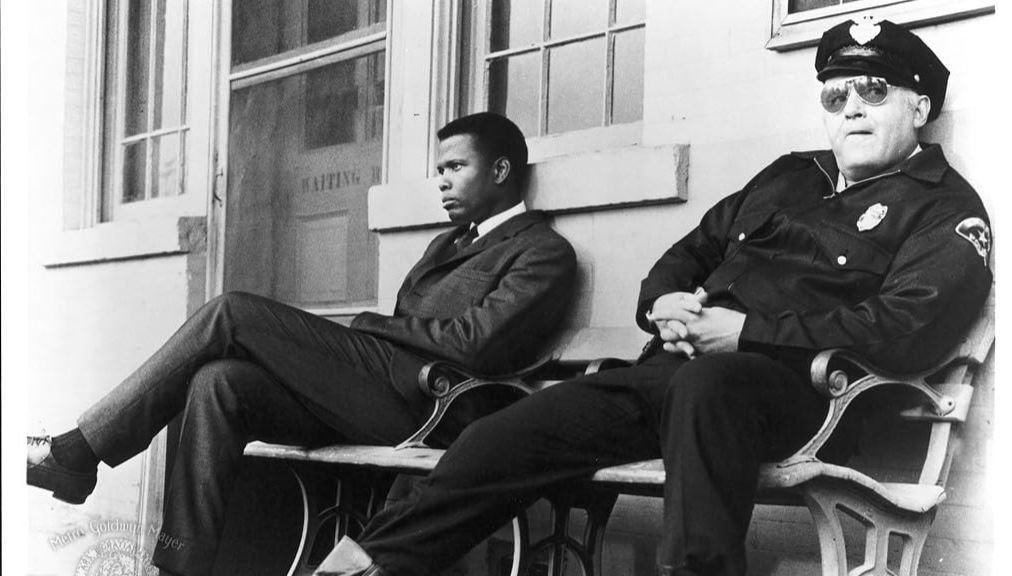

There’s a brief scene in Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night that won’t send anyone scrambling for their film school textbook, but it’s quiet, gracious power never fails to move me. It’s not flashy, or inventive, or even startling, but its simplicity of tone and character reveals more in its few minutes than most movies over their entire running times. Southern Police Chief Bill Gillespie (Oscar-winner Rod Steiger) sits on the couch, while Northern Detective Virgil Tibbs (the always rock-like Sidney Poitier) sprawls out in a nearby chair. They have just finished dinner – most likely the only thing Gillespie could scrounge up from his bachelor refrigerator – and for the first time, they are engaged in conversation unrelated to the murder investigation that has forced them together.

Both men are tentative and defiantly reserved – this is 1960s Mississippi, after all, and this is a black man sitting eye to eye with a white police officer – but nonetheless available to flirtations with openness. Gillespie offers a bleak summary of his life, reduced to “no wife, no kids, and a town that don’t want me.” In a tone slightly above a sigh, he even reveals that Virgil is in fact his first guest. He’s still part of a community that immediately assumes a black man is a guilty man – suit or not – but his fundamental loneliness keeps him from playing the role with any gusto.

It’s not that he’s a liberal saint among bigoted crackers, but unlike his brethren, he retreats to the mediocrity of the self rather than becoming the Bull Connor they all want. Even more, he’s an odd duck not because he sees a black man as a confidant or potential ally, but because he’s one of the few who stares blankly into his life and comes up empty. He has nothing left to give. He’s a man, not a symbol.

And yet, despite admitting his flaws and opening up to someone other than himself for what must be the first time, Gillespie can’t quite escape the mandates of his time and place. Right at the moment when we think he’s reaching out with something other than a bark or an unfair assumption, he pulls back, using a racial epithet to establish supremacy once again. “See here, black boy, no pity,” he spits, afraid of the vulnerability he’s dared reveal to a man he’s been taught to believe is less than human. The escape to prejudice is utterly heartbreaking, but not at all in a way we would first imagine. Still, it sets the tone for the entire picture and elevates it beyond what we’ve always thought it was all these years.

For many, cheapened by years of a less than stellar television show, In the Heat of the Night has been a hot, muggy murder mystery that throws in a bit of racial harmony by the closing credits. In fact, the “plot” is the least interesting thing about it; a forced, abrupt conclusion that leaves us wondering why they even bothered. The story darts around, offers up a few red herrings, and ends with a confession that seems tacked on as if they forgot what the hell they were doing. And if you’re one to look for Grisham-like twists in your tales of murder, the film will surely disappoint. Instead, one should look to atmosphere; the authentic creation of a community that makes us sweat with provincial limitations. As usual, it’s a film made great by small moments often overlooked in the rush to solve the case.

And yes, racism is explored from numerous angles – even Virgil believes a particular white man is guilty of the crime because he fulfills the stereotype of the patronizing “man on the hill” so often found in Southern fiction – but the preferred position is inside his alienation, the true connection he shares with Gillespie. Rather than reduce the friendship of Virgil and Gillespie to a simplistic “awakening” that would insult anyone with a pulse, the film dares suggest that loneliness – as an affliction, a condition, an inescapable identity – is deeper than shared interests, political attitudes, or even race. We know where they stand, after all – arrogant, self-righteous Northerner; bigoted, equally self-righteous Southerner – so there’s no use playing the same record all over again. Each is a man out of step with his world, and by that turn, he usually reverts to comforting hatreds – race, gender, ethnicity – rather than face the fact that he can’t function around anyone at all.

Skin color truly is irrelevant for these two men, because each is just as awkward with what is always crassly referred to as “his own kind.” Even when they end with a truce of sorts, the looks on their faces betray their newfound knowledge, even if, once again secure in their ascribed roles, they fall back on what they can utter aloud without being questioned further. And what a sad truth for us all, really – that when faced with racial hatred, violence, and division, we have an almost instinctive understanding of the terms involved. The language is readily available, it would seem. But alienation? Despair? Isolation? Even now, we can’t quite find the words that grant them reality. And Tibbs and Gillespie wouldn’t dare try.

Leave a Reply