Hotel Rwanda is a good film, but not a great one; an earnest, important work that properly shames the West for its apathy, yet remains beholden to familiar cinematic traditions. It has a nobility and anguish that makes it worthwhile, but good intentions are never enough in the world of film. It is important that we care, but we must do so while marveling at the technique or striking ambition. All told, I’m glad the stars aligned so that this film could be brought to a larger audience, but in many ways, it’s yet another tale of atrocity and victim-hood that may elicit tears for a moment, but will be filed away as the world inevitably produces more barbarism in the years to come.

Director Terry George is surely competent and a talent to watch in the years ahead, but he must find a voice and not let the material overwhelm him. Easier said than done, given that we are dealing with genocide here, but think of Schindler’s List — an indelible artistic mark was left on the proceedings, even as unflinching attention was paid to savagery and slaughter. Here, there simply wasn’t enough, even though I was impressed by the willingness to tackle subject matter that will cause nary a ripple in middle America.

Again, the film’s primary selling point is its rage; not angry enough, perhaps, given that nearly a million people were murdered in a few short months, but more than a play to bleeding-heart liberals who often champion the oppressed so long as they can deduct their donations. In the end, Africans butchered Africans, but the West must be held accountable for its casual shrug while bodies littered the streets. England, France, and of course, the United States — led by “liberal” Bill Clinton — did absolutely nothing during one of humanity’s most nauseating hours, for no other reason than that the victims were black. Left-wing paranoia? Hardly. Rwanda lacked money, oil, and strategic importance, so we turned a blind eye because in the end, humanitarianism remains a conditional enterprise — if you can’t do anything for us, we’ll sit the whole thing out. But what about the latest tsunami disaster, you cry?

Pay attention and I’ll speak slowly: that’s a matter of extra money we have lying around, not a full-scale commitment of our military might. We’ll throw cash at anything (and have), but refuse to send our fighting men unless we’ve received “the nod” from corporate America’s chieftains. A bunch of Africans? Send them a care package, but save our Bradleys in case a pipeline comes under attack. And Clinton was in fact a part of all this, lest you think I’m attacking the Bushies again. Saving lives in Rwanda wasn’t profitable, so we are as guilty as if we had wielded the machetes ourselves. Let Bubba take that shit to his grave.

So yes, I’m glad this film has arrived, although it will be received exactly as journalist Jack (Joaquin Phoenix) said the holocaust itself would be: “They’ll say ‘oh, how horrible,’ then return to eating their dinner.” In that way, films like this are therapeutic, as the comfortable and the privileged feel sorry for Africans for a few hours, then stop by Wal-Mart on the way home and spend as much money on dinner as could feed a Rwandan family of five for a year. And I’m as guilty of crap like that as the next person. I roar and rail about the injustice, hatred, and inhumanity, yet sit on my ass and do nothing.

Then again, I don’t have the U.S. Army at my disposal, so I’m less accountable than the White House in matters like this. Literally all I could do is send money to some organization, only then I’d be just as guilty as those who are generous so long as someone, somewhere pats them on the back for it. Nevertheless, anything that makes uppity white people uncomfortable for a while is inherently good and decent and true, so I won’t be too hard on Mr. George and his staff.

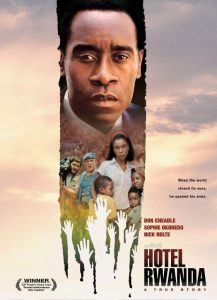

And I will praise the performances, from Don Cheadle (Paul) to Sophie Okonedo (Tatiana), as well as a cast of thousands who toil in obscurity, but bring the required realism and grit. Nick Nolte also appears as a weary UN official; a man who understands the truth better than anybody, and utters the most devastating line in the whole film — “You’re not even niggers……you’re Africans.” He’s not being cruel, only clear. If Rwanda falls, how does that affect the price of crude? Not at all folks, so let them die.

But Paul, despite understanding how a corrupt nation works — bribes, handshakes, and endless rounds of favors — is an idealist at heart; a good soul who loves his country and takes pride in his job, and can’t imagine that the world would close its eyes. It’s fair to say that he’s an African Oskar Schindler, although Paul never wined and dined with the bastards who did the killing. He is a Hutu, yes, and therefore a member of the group committing the atrocities, but he loved his family and community far more than securing fame and luxury (his wife is Tutsi), which attracted Schindler until stricken by conscience.

Paul’s character is better than average because he’s not one-dimensionally noble. One could argue that he’d just as soon take his family and leave, but what about his staff? The hotel where he works is more than a place to earn a living; it is a symbol of comfort and decency in a country that has shown little of either. He works the room, slips bottles of Scotch into the right suitcases, and places a few bills into the right hands because he knows how the game is played, but also because he wants to run a tight, efficient ship. So when hundreds of Tutsi refugees storm the gates trying to avoid certain death, we can imagine that Paul is horrified; not because he despises the “enemy,” but rather out of the dread that these people will disrupt the flow of business. Even after it is clear that the country has exploded in chaos, he still remains concerned about messy rooms and cluttered hallways.

But that’s Paul; not a hero, just a man. He’ll do what it takes to save people (isn’t that what any decent person would do, after all?), but leave him alone and let him choose the methods. As such, Paul is so compelling because he is ordinary without ever threatening to burst forth with superhuman self-righteousness. Then again, he’s not so ordinary that we would mistake him for ourselves (Americans love to believe that they are heroically common). While we made trunks full of money during Clinton’s reign, Paul had guns shoved in his face.

If anything, Hotel Rwanda is a failure of scope; a necessary reduction to the efforts of one man (and he did save lives), which limits the effect of the unthinkable. I’m not sure how a film would be able to effectively convey the blood-soaked destruction of over 800,000 human beings in 100 days, so my criticism is tinged with regret, as I don’t have an answer. I do know that I felt restricted, for I wanted to see the bloody streets and the killing fields with all their maddening implications. I’m from the school that believes we need to see the corpses, lest we get lost in the abstract horror of it all. But it’s clear that American audiences flinch in the face of nasty death. I’m reminded of a CNN program recently where the host stated that he was receiving dozens of e-mails about how “inappropriate” it was that they showed victims of the tsunami (especially children).

And this after a disaster of purely natural origins, so imagine how we’d feel if forced to examine our own dirty work. A headless corpse had a cause — a very human cause — and Americans can’t face humankind’s essential nastiness unless they’re also willing to challenge a host of moral structures and assumptions. It’s one of man’s fundamental weaknesses that instead of asking hard philosophical questions after a massive loss of life (natural or man-made), we shed a few tears; more for ourselves than anything else. Existentialism should sweep the globe after these affairs, but man being man, they clutch their superstitions with even greater ferocity. The saps.

And yes, I wanted more context. We get a brief “lesson” of sorts, but all I could take from that was that the Hutu/Tutsi conflict had its origins in colonial rule (big surprise). Simply put, fuck Belgium. No film should be a dry history lesson, but as this region of the world remains a mystery, it helps to have the names and dates at our disposal. It could be argued that any lack of understanding is my fault (no one is stopping me from reading a few books on the subject), but a film does have a responsibility to educate as well as entertain.

So, while we cry and feel ashamed as the killings continue, we don’t really know how and why it all started. Paul is our guide, and thankfully, unlike misfires like Cry Freedom, we are placed in the shoes of a local, rather than showing how such things affect privileged whites. And yet, I wanted more of Paul; more of his inner world and position in this insane culture, despite wanting the camera to pull above and beyond the cries of one man. Perhaps I’m at fault here, but I’ll do the expected thing and blame the movie. By all means see it (and enjoy it), but shake your head when you realize how much better it could have been.