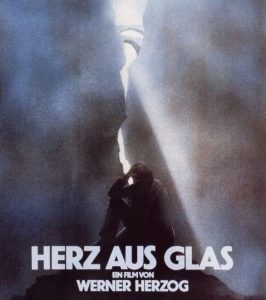

Admittedly, Heart of Glass is a difficult film to review. Comprised of some of the more mesmerizing scenes ever captured on film (specifically the opening shots of the river of clouds and also the glass blowing factory going at full tilt), this bold allegory from

our man Werner Herzog is not easy viewing. And it is not supposed to be. I guess what I find difficult about it is the loose narrative thread and the plodding pace. Taken individually, almost every sequence of the film is noteworthy and entertaining. I feel as if the scenes never link up, even though upon reflection, they absolutely do. I’ve seen Heart of Glass twice now, and yes, it is better the second time, which to me is the hallmark of a good work of art.

Set in a small village in Bavaria circa 1800, the plot involves a master glass blower

who goes to his grave without telling anyone the secret to his beautiful “ruby glass,” red glassware the color of blood. Quite beautiful pieces really, in a bespoke, boutique way. The (for lack of a better term) feudal lord of the village, a man named Huttenbesitzer (Stefan Guttler) who owns the glass factory, is desperate to regain the secret of the ruby glass and essentially destroys the town attempting to re-discover it. Concurrent with this plot, is a prognosticator named Hias (Josef Bierbichler) who lives in the woods.

He also makes dire predictions about the fate of the village and its inhabitants, including the fact that the glass factory will burn to the gournd and the earth will descend into an era of upheaval; destroyed, so it can rise again With me?

Now, before we go any further, you must know that Herzog had the entire cast hypnotized. Yep, every single actor was under hypnosis for every scene. The result, while obviously “weird,” is in a way enchanting. The characters seem to just inhabit space and then arbitrarily begin speaking and/or acting. Odd, sure, yet, as the film goes on the “gimmick” works–at least for me (for his part, Herzog furiously denies the mass hypnosis was a gimmick). Initially it leads to some rather hilarious situations. Like these two guys who are drunk and sitting across from each other at a table. One guy smashes his beer mug on the other man’s head. Knowing Herzog and his penchant for “reality,” this was a real glass, literally smashed on someone’s head. The smashie doesn’t even flinch.

More remarkable is in retaliation, a beer is poured onto the smasher’s head and he doesn’t blink! I backed it up and watched the beer flowing down the man’s face and his

eyes are open the entire time. One can imagine that via hypnosis, Herzog commanded the actor not to shut his eyes. Quite peculiar. Yet, somehow, quite marvelous. There are several other parts where I assumed that Herzog instructed the characters to act in a certain way. For instance, one guy looks absolutely terrified while another man standing

next to him is almost giggling. Mostly though what struck me is how the people really don’t react to each other. It is like taking bad acting and running with it. Characters stare blankly untiltheirs thier turn to deliver their lines. Again, I found it to be plodding, but as the movie went forward, it made more and more sense.

The story gets into gear when Huttenbesitzer decides that he simply must get the formula for the ruby glass. Like many Herzogian themes, the guy’s passion is an exercise in pointless futility and madness. The master glassblower is dead and the secret is gone, yet Huttenbesitzer insists that it must be found. At one point he wants to exhume the dead man’s body and have Hias talk to it. Then he requisitions a sofa from the man’s widow because he feels that the secret must be inside the fabric. He rips it apart with a letter opener, “discovering,” that yes, the formula is in the couch, but it is out of order. In reality, he’s simply holding sofa stuffing. The question becomes, is he simply hypnotized, or just plain mad?

I feel the answer is actually either; both. The actor’s reaction is that he has found the secret all jumbled up, but the character is intended to appear totally insane. The lack of commentary, disagreement and even reaction by the four men standing around him, only adds to the quality of his craziness. Huttenbesitzer then decides that the way to get ruby glass is to take existing examples of the product and throw them into a lake.

The townspeople he assigns to do this abscond with the valuable pieces and smuggle them over the border to sell. Interestingly, I was reading in Herzog on Herzog that in the remote Bavarian town Werner grew up in just after the War, it was common for his mother and others to slip across the border into Austria to trade and barter. Anyhow, Huttenbesitzer eventually goes so completely nuts that he kills his maid because he feels that human blood is the secret to ruby glass. Similar to Aguirre: Wrath of God

insomuch as the obviously senseless (to the viewer) pursuit of material goods leads to quite horrific but entirely avoidable ends.

Hias spends a good deal of time making predictions which are quite obviously about the future history of Germany, specifically World Wars I and II. Stuff like the country will go astray and a giant from across the sea will come and defeat it. While I appreciate what was being expressed, I found the metaphor too obvious. Also, perhaps a bit unnecessary since Huttenbesitzer’s mad quest is also an allegory for Germany’s crazed pursuit of land and power that ultimately led to both World Wars. Still, I have a hard time faulting the film because it is so far out of the mainstream, so truly different that I may not have “got it.”

I’m not talking about some David Lynch drek either where there is no meaning yet people jump through all sorts of hoops saying, “maybe he meant this” and “maybe he meant that,” no. I fully understand what Heart of Glass is about, but I know that only subsequent viewing will reveal the “why” behind how the story was told. Take for instance the hypnosis, ostensibly a stunt in my mind the first time I watched the film, now seems to be quite significant to the message. How exactly, I can’t say concretely, but my current theory is that Herzog and writer Herbert Achternbusch are trying to show us that “normal” human behavior is exactly as prescribed as the actions of those under the spell. We’re all just walking automatons, reacting to phenomena in predetermined ways.

That’s my current thinking at any rate. Anyhow, Heart of Glass is bold, challenging filmmaking that requires an active, maybe even proactive, viewer. And I don’t want to make the film seem too academic, for it isn’t. Be sure to check out Huttenbesitzer’s father who has not gotten out of his chair for more than a decade and does little else but laugh manically. Towards the end, when the town is in flames (literally) and he does indeed stand, all he can do is wander around his mansion looking aimlessly for his shoes.

That’s my current thinking at any rate. Anyhow, Heart of Glass is bold, challenging filmmaking that requires an active, maybe even proactive, viewer. And I don’t want to make the film seem too academic, for it isn’t. Be sure to check out Huttenbesitzer’s father who has not gotten out of his chair for more than a decade and does little else but laugh manically. Towards the end, when the town is in flames (literally) and he does indeed stand, all he can do is wander around his mansion looking aimlessly for his shoes.

Essentially, Armageddon has come down on his head and he is so myopic that he doesn’t even notice. Drowning in the minutia, so to speak. Good stuff, and I’m

undoubtedly going to have to watch Heart of Glass again. Which is fine, because this film is not only filled with gorgeous imagery and intriguing scenes, but how often do we find films that demand analysis?

I just need to put all the pieces together and see it as a whole, not as scattered vignettes, and I look forward to doing so. If you are a fan of Herzog, even just a little, I recommend this movie for it is one of the more obscure and opaque films from a director known for exactly that. Plus, like all Herzog films, Heart of Glass is a treat for the eyes. Especially on DVD. Oh fuck… maybe I should just listen to Herzog’s commentary?