The greatest of cinematic sins, now and forever, is over-explanation. Tying A to B when C is a better bet. Reducing the complexity, nuance, and maddening ambiguity of life – any life – to simpleminded reasoning rooted in dime store psychology. Even the worst of us – and increasingly, that seems to be all there is – deserve more than a cursory glance at the past, for no one action is ever simply the result of any one cause. In any piece of art worth a damn, then, especially biographies and character studies, it’s best not to reduce the whole of an experience to a single moment in time. As such, great men can be bastards, and bastards can be great men, as if I had to say that out loud. But there is the tendency, most often among the school of resentment set (consult Harold Bloom for more detail), that believes art must uplift at all costs, and any and all artistic endeavors must scrupulously avoid giving refuge to scoundrels.

Thankfully, we have Mike Leigh. Not only is he going to eschew cheap moralizing, he’s rarely inclined to give us even the mere hint of a story. Certainly not one with conventional trappings. If it’s plot you crave, you’ve likely moved on from the likes of our man Mike, if you ever held him close to begin with. Leigh, as with all great minds, wants to present life as lived, and it’s up to you to figure everything out. He assumes a wise, literate audience, which is perhaps his one great failing, but if you are so inclined, the rewards are ample. It’s the ultimate empowerment for any viewer. When we can pick around the art of our choosing, armed only with our curiosity, it’s a good bet we’ll emerge with a greater understanding. Not only of the lives on display, but just as likely for humanity as a whole. He’s on our side, and he trusts us to proceed with eyes wide open.

Which brings us to Pansy (Marianne Jean-Baptiste). To call her angry and bitter is to minimize the situation with an unprecedented level of misunderstanding. From morning to night, she complains. Blows everything out of proportion. Lectures and sermonizes with humorless precision. Even the simple act of shopping for furniture becomes a battle royale of righteous rage. That chip on her shoulder long ago graduated to a boulder, and she clings to it as the only life force left to her. And when the world won’t comply and push her to despair, she’ll contrive new reasons to get upset, thereby justifying her sour pickle of a visage. “I told you so” as the ultimate mantra, when she’s responsible for the very mess she derides. But mostly she naps. Escapes. Turns a blind eye because she lacks the ability to articulate the deeper source of trouble. Like everyone consumed by self-loathing, she directs everything externally. Far easier to point elsewhere to avoid, well, the hard truths. About oneself most of all.

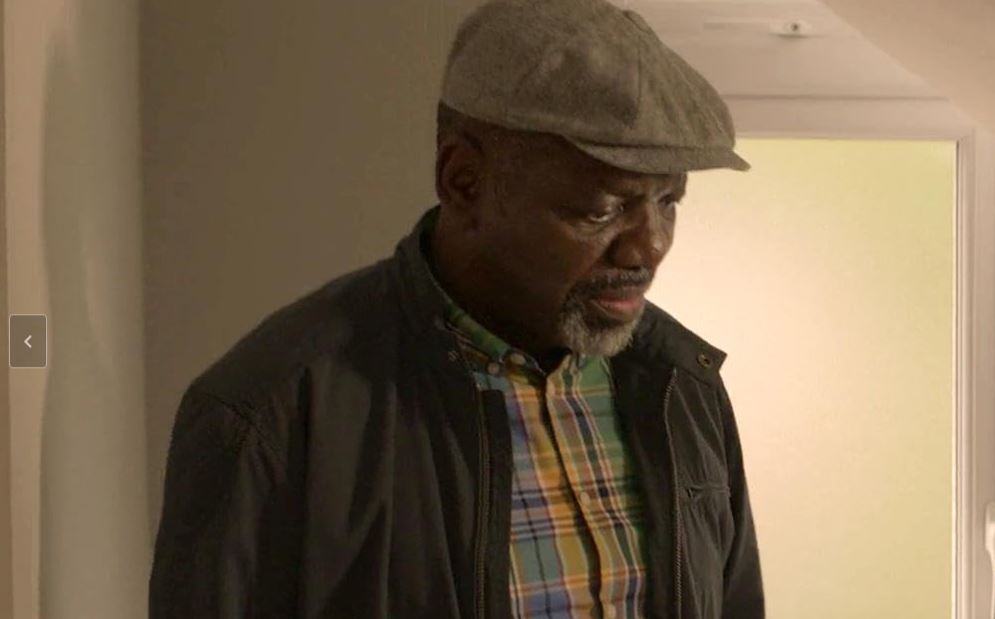

Again, if it seems as if I’m meandering around the point and not getting to the movie itself, please remember: the movie is as I’ve presented. Pansy moaning the disgust of the ages not because it’s warranted, but because she can. Not that she doesn’t have a legitimate gripe or two. Yes, her son is a passive, disinterested layabout, and could the deadbeat get a job anytime soon? Pansy’s husband, by all appearances a good and decent man, may in fact not be the dedicated, active listener she needs him to be, although it’s safe to conclude that he long ago tuned out the proceedings just to survive. If he gave every last shout the attention she demands, he’d likely have succumbed to bed rest himself. Perhaps the grave. But say what you will about him: he’s there. Working by day, staring into space by night, and always on hand as a warm body constituting an audience. Why hasn’t he left? Sought succor in the arms of another? Maybe that’s at the bottom of things: to be a man worthy of the name, you’ve got to be the sort who stands tall in his own defense. At minimum the kind who considers an alternative. Sitting there and taking it only prolongs the abuse.

Still, no answers are forthcoming. Has he cheated, hence the belief that he has to endure the vitriol? It’s because our cultural consumption too often traffics in cliché that we believe he – or anyone – has to have done something to be at the ass end of a shrieking spouse. It rarely enters our minds that the Pansy’s of the world could, possibly, just be. Nasty as an instinctive existence. Isn’t it possible? Don’t some live charmed lives and still end up greedy and awful? Conversely, how is it that so many who grow up under a litany of traumas end up with kindness and love? Leigh, bless his glorious, unconventional heart, believes it’s possible. More than that, highly probable. Certainly more interesting. While others believe in a minimum of sainthood to generate our sympathy and admiration, Leigh and the like-minded know it’s never that easy.

As Pansy moves along her days, claiming ailments that almost certainly do not exist, or roaring about family strains we all share, she never moves in any one direction that gives us real insight. There’s never a hushed conversation where we get a glimpse of hidden abuse or lies that finally get a proper airing. There’s a sister about, however, and it is her decency that acts as a striking contrast to Pansy’s disgust. Didn’t they grow up in the same household? How on earth can they be so different? Because siblings always are, and no one’s destiny is ever carved out from birth. And we, out there in the dark, are free to supply stories and explanations of our own amidst the silences. And yes, Leigh would be the first to say they all contain a hint of truth. Surely there’s something big she’s hiding, right? A bombshell to set us straight? Maybe. Likely not. Pansy is fully capable of hating life absent any particular reason she’d be justified for doing so.

As we grind towards the film’s conclusion – and it is a grind, given how unpleasant Pansy remains every waking moment of the day – we cannot be faulted for thinking a reconciliation is in the offing. Maybe the flowers her son bought her for Mother’s Day will turn the tide. You’d think so, only Pansy’s husband threw them in the yard. Perhaps the recent visit to her own mother’s grave site will stir up a renewed desire to patch up the problems of the past. Pansy repeatedly exclaims her exhaustion, so yes, it does seem like the proper course to breathe, relax, and live each moment without the weight of the world on your back. It’s bad, but maybe not that bad. Okay, then, a hug is on the way. An apology. A commitment to do better. To change, against the odds. That is, after all, the way of fiction. Give us on screen what we can’t get in life. Leigh isn’t having it.

As you let the final moments of Hard Truths wash over you, remember that I warned you. They won’t satisfy. I mean, they will if you admire veracity, but you’ll leave with even more questions. Why? Why not? Where is this family headed? What can be done? You’ll never know. Neither will anyone. It’s fully reasonable to believe Leigh himself didn’t know as he put pen to paper. The only clue Leigh is willing to drop is through the inclusion of other characters (nieces, neighbors, etc.) who actually have things to complain about. Humiliations and frustrations alike, just by virtue of working and walking around. Only they don’t become Pansy. Not even close. And therein lies the hardest truth of all: the mere fact of existence is an impossibility. Luck, as Woody Allen would say, is all. Happenstance and the inexplicable shaping our ends. One answer as good as the next. To some, hopeless and futile. To others, liberation. We all, at every turn, want to know why, when we’d better get used to the uncertainty.

Leave a Reply