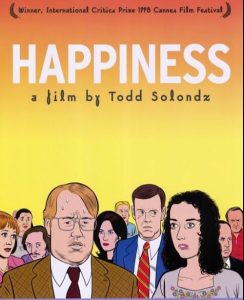

Happiness is the meanest, most misanthropic film I have ever seen, and as such makes me smile. I love this film with an unsurpassed affection, and to know that it was made against all the odds and all the possible objections that were no doubt raised along the way, gives me the same sort of triumphant joy I experience when reading about nursing home fires or school shootings. Todd Solondz has crafted a brilliant, timeless classic that will be just as fresh a hundred years from now, as no doubt mankind will be as sick and depraved then as they are in the present. Not only is Happiness my personal choice as the best film of the 1990s, it acts as a litmus test for all potential friends and acquaintances I may encounter in my life. If you hate it or even express a minimal level of disapproval, the conversation will end. It is simply beyond my abilities to trust anyone — man, woman, or child — who cannot readily endorse the vision of this film. It is one of the few cinematic experiences where I knew I was in for greatness after the opening scene. And when we reach Dylan Baker’s dream sequence of a gunman run amok? Christ Almighty, I didn’t know whether to cheer with sympathy or laugh my ass off. So I did both.

Happiness is sick, twisted, vile, vulgar, and cruel, but it never strains for effect. As such, it is never unfair. The characters we see make terrible choices, act in direct opposition to common sense, and are usually unsympathetic, but that is precisely why they are so endearing. Nothing irritates me more than a character who begs to be loved (and you know the Italian, Oscar-winning asshole I’m thinking of here), and these people have no such agenda. Some have criticized the film for having a compassionate view of a pedophile, but that simply demonstrates the hateful biases of the critics. No, my fiends, the child rapist is not treated “well,” nor is he “understood” or even “loved.” He is simply presented fairly; even-handed and without obvious political grandstanding. His behavior is simply that — behavior — and it appears supportive because we have come to expect child molesters to have horns and wide-eyed looks of madness, like he’s Peter Lorre in M or something. Solondz understands that those we consider monsters are “normal” in appearance and it does little to point out the obvious. What good would it do anyone to state that a pedophile is a revolting villain who deserves the gas chamber? Instead, Solondz takes a huge risk, but an eminently sane one, as he refrains from judgment. The director is not here to flatter the audience and reinforce their prejudices. Such ambivalence rankles the self-righteous because their worlds lack subtleties, but I cannot think of a better way to present such a character.

Dylan Baker’s child rapist is, after all, a devoted family man who has certain needs that must, at all costs, be fulfilled. No one would argue that he should act on such impulses, but again, saying that merely points out the obvious. And we don’t need a film to tell us that. Solondz, if he has an agenda of his own, argues the following: each of us, regardless of social rank, attractiveness, or intelligence, desires affection and love, however we might define those terms. Because not all of us possess the skills to secure a mate, or the wisdom to con some tart into the sheets, or the money to secure a prostitute, we are usually left bereft and confused as to how we might fulfill our passions and longings. Some choose personal ads, others random hook-ups, and others — bear with me — might choose rape. Some prey on the innocent, some push cane-carrying grandmas against the wall for a quickie, and others slam their sausage into the nearest furry critter. Whatever the choice, it must be that which quenches a thirst. Of course, any society has the right to punish particular sexual behaviors, but Happiness (like all rational adults) must move beyond simple notions of right and wrong to arrive at a better understanding of desire.

Loneliness does strange things to a man (or woman, although it seems more men are willing to act on their often bizarre impulses), and I would be the last one to wag my finger. Again, these people have limited resources on which to draw, and they are forced to use tools that may appear primitive, short-sighted, or selfish. As I stated in my review of Monster, society establishes certain things as desirable (almost necessary) and then cruelly assumes that everyone can reach those goals using “acceptable” methods. It is similar in matters of the heart and loins. Only here, lust and sexual energy are biological inevitabilities, which makes the lack of fulfillment that much more dangerous and crippling. It is no different than Madison Avenue’s current method of tying sex to everything we see, then imposing sanctions when we want to move beyond mere voyeurism. Don’t tell me that it is my duty as a man to have a hard cock then give me no place to put it.

Ah, but the movie. I love each of these characters so dearly, that I feel right at home in their presence. Over there is the aging crab apple (Ben Gazzara), who leaves his wife not for another woman, but rather to be alone. When he does have a quickie with some aging floozy, he responds to her query “How do you feel?” with the despairing, “I don’t feel anything.” It is simply beyond anyone’s comprehension that he has no need of romantic company. That is his way of dealing with his desire. And over here is the clueless pervert (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who can only relate to the object of his fantasies through anonymous telephone calls. And when he does find an actual woman he can talk to with breaking into a cold sweat, she’s an obese killer who broke the doorman’s neck and carved him up into pieces. Still, she’s no more a freak than anyone else. She’s hostile and has twisted views about sex, but that is how she deals with the world and Solondz isn’t sanctimoniously tossing her aside. And the others — a dippy wife who believes she “has it all” while her husband is greedily raping the neighborhood boys; a skittish mouse of a woman who, in an idealistic rush, wants to help immigrants only to be sexually exploited by one and treated with contempt by the rest; to a young man, confused by his father’s lack of interest in him sexually, who sees his first ejaculation as a moment of moral triumph. These people sound like characters out of a Satanic circus, but they are so completely themselves that they represent true cinematic advancement in the portrayal of flawed human beings with needs, many of which we believe we can’t understand. But if we look closely, we can understand because need is universal and usually messy and disorienting. Sappy garbage like Big Fish tries to comfort us by perpetuating simple “boy meets girl” silliness, but we rarely know why we fall in love, and sexual urges add an extra dimension to an already complex situation. Boys want girls all the time, but for what? A walk in the park? To help with a foot fetish? To strap on a dildo and turn the boy into a girl? Happiness isn’t arrogant enough to have all the answers.

All of us want to be happy (or at least believe such a state exists), but it simply cannot be so. We are indeed lucky if we find a few moments of it from time to time, as life is unending in its cruelty, callousness, and relentless push forward. Internalizing what we believe is supposed to make us happy (in America, I’ve heard very few deviations from “house, car, family”), we dance our little jig and wonder time after time why we still find little but disappointment and sadness. I would argue this (as would Solondz, I think): the only happy man is he who acts on every impulse. This is impossible from a practical standpoint (society would be consumed by chaos within minutes), but are we not selfish beasts? Being thwarted — in a job, with our spouse, or even in traffic — brings out our true natures, for we feel entitled to whatever it is that brings about contentment. No one is arguing that Solondz would make a wise and efficient statesman with such a philosophy, but he’s not arguing for implementation. In his misanthropic worldview, he is saying that all of us want something, but we are usually too stupid, dense, or reckless to know what that is. Perhaps we are insane because we believe we should be happy at all, as if joy were an entitlement given at birth (oops, it is for us Yanks, which could be part of the problem). So until we find out what Happiness is (or until we discover it is but an illusion), we will fuck, masturbate, kill, eat, make prank calls, steal, and fantasize ourselves into a numbed state of distraction.