Written and Directed by Ishir´ Honda

Starring:

– Godzilla

– Akira Takarada as Hideto Ogata

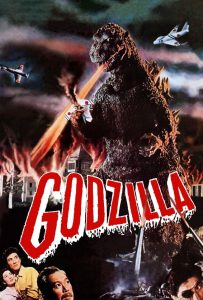

The original, uncut version of 1954’s Godzilla is a much better film than the butchered, ridiculously dubbed crap featuring Raymond Burr, but it’s still not a great film, even if its pacifist message (and blatant anti-Americanism) takes central stage. Yes, there is a certain charm to the cheap effects and silly “monster,” but I don’t remember the film being this slow and uneventful when I was a kid. Fine, my memories are of the shortened version that was barely an hour in length, but I can’t deny that as it is seen here, there isn’t enough of the giant lizard for my taste. When Godzilla storms through a cardboard Tokyo, setting the city aflame (in an eerie parallel to the American firebombing of World War II), I was quite involved, as only a joyless crank would fail to enjoy cheesy horror. At the very least, I admire the effort, and a lack of technology should never get in the way of one’s entertainment, even if what we are witnessing is obvious artifice.

That said, the political nature of the film (where Americans are called devils, even if indirectly) is quite powerful, even now, as the context of the film’s original release never really leaves us. Remember, Japan had just been humiliated by unconditional surrender, war crimes trials, and a lengthy American occupation at the hands of “Emperor McArthur.” Most of the island chain was in ruins–atomic in nature or otherwise–and a sense of identity was difficult to find amidst the rubble and subservience. Fine, Japan deserved their fate as they raped China from end to end and tortured and/or murdered hundreds of thousands of civilians in Asia and the Pacific Rim, but as a nation brought to its knees by militarism and war, Japan understood that if the world continued in its dance with weapons of mass murder, the horrors of the 1930s and 1940s would seem like romps through the park. Japan had little right to be self-righteous given its legacy as a barbarian, but as the only nation ever subjected to nuclear weaponry, it did have a duty to warn the rest of us of the effects of this new form of “combat.” Godzilla, then, was a tangible reminder of what would happen when human beings went too far in their quest to dominate the world.

The film continues to remind us of this bargain — increased scientific knowledge in exchange for the risk of annihilation — while throwing in references to Godzilla’s mighty wrath. There is a tortured scientist who has developed an even more heinous weapon — The Oxygen Destroyer (nothing like being literal, right?) — that has the capacity to kill every living thing in a particular body of water. There is no question that this scientist represents the conscience of the new Japan, as it wonders what other novelties will cause endless awe and an equal amount of trepidation. Needless to say, the invention will be used to destroy the beast, although the film ends with the warning that it is but a temporary solution. More H-bomb tests, after all, will awaken more sleeping giants, and Godzilla will return again, perhaps even more pissed off than before.

Despite the talky nature of the film, or its pained earnestness (what 1950s schlock-fest didn’t have a lesson for humanity?), it did feature Kurosawa staple Takashi Shimura, who seems far too good for the material. He is serious, contemplative, and thoughtful; qualities that don’t really belong in a film starring a man in a rubber suit. One can understand the intent of the film, and I have no doubt that Shimura believed in it at the time, but as I’ve seen too many masterpieces with his participation, I can’t help but think he’d be embarrassed in retrospect. Nevertheless, the original is far, far, superior to the 1998 Roland Emmerich atrocity, which was so bad that any planned sequels were cancelled immediately after the initial screening. It was clear that the franchise was not in need of an update. And I must admit that when it comes to Godzilla, I’ll always prefer the unapologetic crap — you know, the “vs” films with King Kong, Mothra, and, best of all, a cute little son. At that point, Japan no longer suffered from an identity crisis and to signal its return to the world stage, it greedily went after the money with as much determination as it had initially pursued the mission of ridding the world of nuclear weapons. Perhaps that too has a lesson for the world — the surest sign of a nation’s success and power is a concurrent decline in the arts. Godzilla was never that, exactly, but it tried to be more than pure escapism. In that, I guess it succeeded well enough.