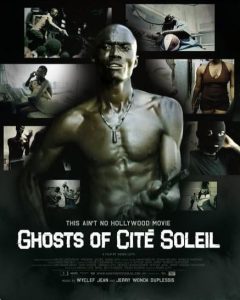

If Haiti is hell, Cite Soleil, a ghetto inside the city of Port-au-Prince, is the hot poker up the ass within hells gates; a neighborhood so violent and depressing that the United Nations recently saw fit to label it among the world’s most dangerous areas. It’s an astounding distinction in light of the world’s current depravity, but after Asger Leth’s sobering documentary, the Honor is indeed well-earned. Fortunately, Leth lets his camera run and never attempts to interpret the events that play before us, and he lets his subjects speak without inhibition or spin.

The central figure, a gang leader who goes by the moniker Haitian 2pac, is, under the circumstances, a charismatic figure, but a young man so immersed in the madness of his country that we sit and wait not for his future, but the hail of gunfire that will surely end his life prematurely. But 2-pac knows this, and speaks openly and matter-of-factly about the destinies of his brethren. Without a gun, you have no power, he states, and this is never truer than in a country where leadership consists of one failed president after the other, all of whom either resign in shame, end up dead, or flee in yet another coup attempt.

2pac is the head of a gang known as Chimeres (ghosts), armed thugs paid by President Aristides regime to intimidate the opposition, with deadly force if necessary. It’s quite remarkable that the countries poor have been co-opted by the ruling classes, but hunger has a way of erasing moral and ethical lines. The gangs are interested solely in survival, and given what we see of the city, it’s a wonder anyone lives long enough to have children. The images and words of Cite Soleil are balanced with reports of the dying regime; accounts that show how ex-loyalists now known as The Cannibal Army seek to overthrow Aristide and, presumably, install a government that will no doubt begin their reign with calls for idealism and reform, only to descend into greed and murder in a matter of months.

But Haiti goes through the motions of this sad dance nonetheless, which makes the whole scene that much more heartbreaking. People want to believe progress is possible, but kids like 2pac know better. Haiti will never change, he says, and, in a twist, the mouths of babes speak with ultimate authority.

If there’s a weakness to the film, it is the very monotony that is necessary to convey the desperation. While we cut to street demonstrations, random gunfire, and power plays among Aristide and his men, we spend most of the time with 2pac and his minions, reiterating the same points again and again. And if there’s a hidden story here, it is that of Lele, the French relief worker who falls in love with 2-pac, despite the fact that he’s a cold-blooded murderer. No, I’m not advocating that yet another white-face tell the story that non-whites can do for themselves just fine, but I couldn’t help but wonder how this woman — who we never get to know in any real way — came to Haiti, entered a literal war zone, and found love and romance with a young man who worked as a hitman for Aristide.

What on earth happened to her sense of duty to a greater cause? Furthermore, is she still employed? That Haiti is a horribly brutal place with no hope or possibility of development is so well-established as to be obvious. Why not, then, take viewers in a direction they never would have expected? That said, I never anticipated an appearance — even via the telephone — by Wyclef Jean. His words of advice to 2pac regarding a music career, given 2-pac’s later death, seemed both cruel and a saving grace. After all, it’s all the poor boy ever really had.