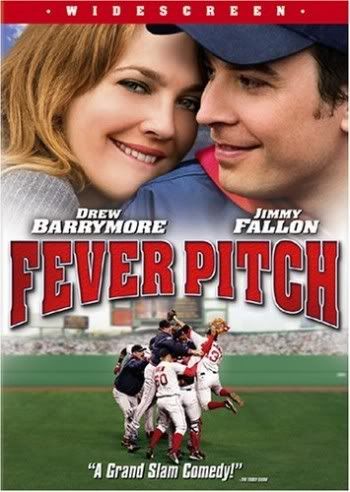

Fever Pitch is a muddled, surprisingly subdued comedy with one great scene, a few minor guffaws, and long stretches of Drew Barrymore proving once and for all that even an inconsequential script is beyond her capabilities. She’s good at whining and pouting, of course, but I imagine acting has nothing to do with it. When she’s asked to be taken seriously as high-powered executive Lindsey Meeks, for example, we are immediately transported to that world where fashion models ponder the mysteries of the universe and bubble-headed ninnies produce lasting works of philosophical complexity. Drew working a drive-thru window or as a Wal-Mart greeter?

That I can handle. But the sort of woman who is so coveted by corporate heads that she is told with all sincerity that her work is brilliant? No one should be asked to suspend that much disbelief. And I’m not even sure what it is she does in this film, other than the fact that it involves office buildings, computers, and long mahogany desks covered with folders, pens, and half-empty coffee cups. Whatever it is, it literally consumes her, a fact that keeps her from having a semi-normal love life.

And then there’s Ben (Jimmy Fallon), an obsessive Boston Red Sox fan who also happens to teach geometry, which just might be harder to swallow than Barrymore’s employment status. Once baseball season begins, Ben plans each and every day around the games, even using sick days to cover the gaps. His apartment resembles a young boy’s fantasy, from the Red Sox sheets, towels, and wardrobe, to the plastered walls and framed magazines. Even the arrival of season tickets (a lifetime gift from his late uncle) is a ritualized affair; Ben and his buddies do everything but weep uncontrollably. His fanaticism is juvenile and odd, but no more so than Lindsey’s workaholic lifestyle; one is simply more socially acceptable as an obsession.

Ben and Lindsey fall in love–of course–after a brief courtship where they don’t say much of anything to each other, which is pretty much standard in Hollywood romantic comedies. We’re asked to believe that making faces at each other or walking aimlessly through parks is enough to secure a lasting bond, although I can imagine many real people coming together over far less. And their love affair just happens to coincide with the off-season, so Ben can seem like a devoted, relatively normal kind of guy. But when April hits, he’s transformed into what she calls “Summer Guy,” or “the sort of man who is equally devoted to something that isn’t me.” If there is a minor strength to the film, it is in this battle of the sexes; where women are threatened by men’s interests if they can be enjoyed without her company. This is a real promblem worth exploring. Ben takes Lindsey to Opening Day, as well as many other games throughout the season, but it’s clear that he could just as easily be sitting next to a stuffed animal as a fellow human being. To make matters worse, she’s ignorant regarding the Red Sox, and not much better with baseball as a whole.

When Lindsey senses that she’s making the frequent mistake of conforming to a boyfriend’s lifestyle, she pulls back and questions the nature of the relationship. It’s fine that she holds to her identity, but then she goes too far in the other direction and asks Ben to compromise his love affair with America’s pastime. For example, she genuinely cannot understand why Ben would rather go to Fenway for a date with the Yankees when a tedious birthday party is waiting in the wings. But like a typical emasculated pussy, he caves and misses one of the most glorious comebacks in the history of the franchise.

Of course, this kills Ben and he lashes out in one of the few scenes that had me rooting for a character played by the usually loathsome Jimmy Fallon. His rage and frustration speak to the difficulties most men must face when dealing with a female who won’t accept not being the center of the universe. And whenever a man hears the word “compromise,” what he’s really envisioning is an endless series of small cuts to his genitalia, topped off by a complete transformation into something he couldn’t possibly recognize. Women deny it, but their goal with the opposite sex usually involves breaking him down, overhauling the body and mind, and rebuilding the blob as something she can control from the bedroom to the kitchen. At this moment Ben resists, and we are thankful for his rebellion. And yet, it doesn’t last. The prospect of just shutting the dame up is simply too powerful.

Ben gets even worse when he starts to miss the frequent trips to Lindsey’s vagina and announces that he’ll sell his coveted season tickets for $125,000. Lindsey won’t let him do it, but the fact that he was one minute from signing the deal proves how weak men can be when faced with a loss of oral stimulation. It’s our downfall as a species. Ben is also pathetic during the obligatory “late” sequence, where at first he seems indifferent to the idea of becoming a father, but then caves by buying a Red Sox baby outfit.

This little scene rings false from top to bottom, especially when Ben learns that Lindsey has finally had her period. Every honest guy from coast to coast would hang up the phone, dance a jig throughout the apartment, and pump his fist with joy as if he’d just won the lottery. Here, Ben is quiet and mournful, which is how he’d react in her presence, but not when alone. The truth of the matter — and one that chicks don’t like to hear — is that all that baby shit is a woman thing, and men just play along to maintain harmony. And to keep the supply of pussy fresh and uninterrupted. Any man who says he’s all tingly and excited by “home and family” is either a castrated milquetoast or a liar — usually both.

The one great scene I spoke of involves the short break-up; where Ben is so distraught that he locks himself in his apartment, surrounds himself with buffalo wings, and watches a tape of the Bill Buckner gaffe over and over again. His glassy-eyed stare, coupled with a face covered with sauce, is truly inspired because it makes sense for his character. Yes, we agree, this is exactly what he would do when faced with tragedy and loss. The second laugh occurs a few minutes later after Ben’s friends bust in to save him from ruin. Slapping some sense into him and throwing him in the shower, one of his friends begins to shave his balls with the concentration of a surgeon. I’m not sure why I chuckled, but I’m usually taken by scenes that make absolutely no sense whatsoever and relish in that fact.

Again, Fever Pitch is largely forgettable and certainly predictable (and not just because we know the Red Sox finally shatter the Curse of the Bambino), but it’s not a complete waste of time. Ben and Lindsey fall in love because the script demands it, but I never expected a Drew Barrymore film to end with ambiguity or even the hint of tragedy. I had to accept that I’d be let down from the beginning, and that alone saved me from an early exit. And hey, any film that shows off a wonderful city like Boston can’t be all bad, even if we wonder why a lifetime resident like Ben fails to have an accent.

And because we are in the world of the Farrelly Brothers, we know there will be vomit jokes, gay baiting, and at least three cripples. And after There’s Something About Mary, there will also be some chick who looks like she’s had her skin baked by a flame thrower. Still, better heads prevail and immaturity is kept to a minimum, which might actually work against the movie. So many scenes just limp along with no spirit that I would have liked a screaming retard now and again to shake things up, although Ben does have that slow friend who is obsessed with sponges. No, not Drew, the other one.