I’m convinced that no one returns from the sea unchanged, and more than any other form of adventure available to the ever-curious human animal, it holds the greatest risk of madness and death. The lust for exploration is built into our very DNA, and we the timid owe a great deal to those who pushed beyond their borders to better the lot of mankind. But now that the conquering spirit has been tamed by our modern age, all that remains is adventure for its own sake — contests, competitions, and collisions of ego that might hold vicarious thrills for spectators, but by and large are little more than senseless trips of vanity.

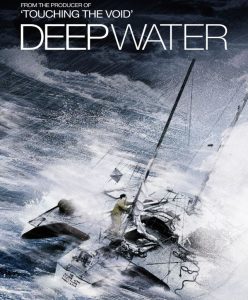

So if we are to concern ourselves with these stories any longer, there must be an insight into the human experience that moves beyond mere winners and losers. Thankfully, Deep Water is just such a tale; a documentary that begins with a now-forgotten competition (a 1969 London Times-sponsored event that would bestow a cash prize upon the first man to complete a solo boat trip around the world), and winds up as an examination of man’s fragility so profound that it leaves us stunned.

Donald Crowhurst, a well-liked, easygoing sort of chap who earned his bread as an engineer, but was far from an expert in seafaring, is the central focus of the story, and it is his bizarre end that makes us wonder why he ever agreed to set sail in the first place. Because he was forced to seek financing for his boat, he remained contractually committed to finishing the race, as a clause stipulated that if he bailed out or failed early on, he would be forced to repay the loan. Needless to say, this would have resulted in financial ruin. That fact alone might explain his subsequent behavior, but the isolation of the vast ocean is arguably more to blame, and we are fortunate to have home movies of his voyage, as well as extensive diaries and ship logs.

It turns out that while the other competitors were pushing from England to the Cape of Good Hope and beyond, Crowhurst was adrift near the Brazilian coast. A leaky boat played a part, but as the race moved from one dreary month to the next, Crowhurst cut communications in order to prevent home base from being able to track his position. Evidence revealed after the fact showed that he clung to the shore because as his fellow travelers rounded Cape Horn for that last push to the finish, he would join them and pretend that he’d completed the same journey himself. Was his deception a calculated effort to win money and prestige, or had he simply lost his mind?

Crowhurst must have known that close scrutiny of his logs would have revealed his lie, so it appears that that very realization forced him to try instead for a second-place finish. He would save face, but no one would bother to look more deeply at a man who had lost. But in a stunning turn, the actual leader sank as he neared England, and because the others had either dropped out or gone mad (one competitor turned away suddenly and decided to go around the world a second time), he was left alone to collect the top prize. Faced with that reality,

Crowhurst disappeared, though his boat was later found. The record he left behind reveals a man besieged by loneliness, self-pity, hopelessness, and existential fury, but no clue as to how such a mild-mannered man went so rapidly off the rails. Could the British obsession with stiff-upper-lipped pride have been enough for a man to willingly leave behind a wife and family? Whatever the cause, this is documentary filmmaking at its finest; dramatic, thrilling, and always remembering that the best stories are often little-known events placed in a larger, deeper context. A must-see, if you can find it.