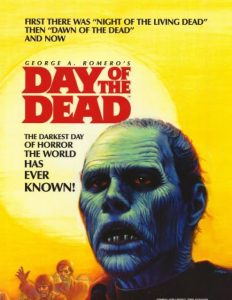

George Romero’s Day of the Dead never gets any of the credit extended to Night of the Living Dead or Dawn of the Dead, but in its own way, it’s an underrated gem. All one can ever ask from a zombie flick is that it tickles the funny bone, shows healthy amounts of gore and cannibalism, and takes a satirical shot or two at American culture. And while Day of the Dead isn’t as obviously pointed as its two predecessors, it does level a few attacks at the military that are unmistakably hostile. There are long stretches without any zombie action, but when it does hit, we are more than grateful. For some reason, I am always comforted when I see several of the undead fighting over a scrap of small intestine, almost as if it’s Romero’s signal that all is right with the world. In each of these three films the world is stumbling to its brutal end, but that is indeed why I remain so relaxed and optimistic. Only when the munching begins can I muster a crooked smile.

This time around, a group of survivors have taken refuge in an abandoned missile silo in the swampland of Florida, and once again no explanation is provided for the zombie takeover. At this point it is safe to assume that the undead have become the standard and that “normal” human beings are odd and out of place. Most of the survivors are military men, a fact that allows Romero to portray them as they are, heightened by the circumstances of their isolation. Despite the fact that humanity has been wiped clean by a zombie plague, these louts are still playing soldier; establishing rules and regulations that speak to their inherent need to boss others around. Rather than cooperation, the Army pigs roar, bellow, and throw their weight (and guns) around, as if their obsession with protocol had any relevance at a time where flesh-eaters roamed the earth. Their boorish, aggressive behavior reminded me of Colonel Bat Guano in Dr. Strangelove the world is coming to a fucking end and he’s more concerned with the sanctity of private property.

The story in Day of the Dead also involves a half-crazy doctor and his experiments that are meant to determine the “nature” of the zombies. With the help of the soldiers, Dr. Logan dissects the undead and attempts to isolate that which motivates their lust for flesh. He notices that even without any internal organs, the zombies continue to hunger for humans. It is instinct, he determines, not a need for sustenance. The doctor has also pacified a zombie he calls “Bub,” who has been trained to perform simple tasks and recognize books, music, and his former military training. In the end, Bub even learns to fire a gun, a skill that comes in handy when he is forced to plug the head asshole. These scenes are among the silliest of the zombie trilogy, but we like Bub, and almost hope that he is given a chance to live a normal life.

Of course, things go wrong, the doctor is murdered by the soldier in charge after his more graphic experiments are discovered, and the suicidal Pvt. Salazar runs to the surface, invites hundreds of zombies to the platform that leads to the underground lair, and proceeds to infest the hideout. At this point, the zombie holocaust truly begins, and the special effects wizards finally do their thing. It is a great pleasure to watch the macho soldiers get torn apart, and an especially gratifying scene features a burly private who has his lower half ripped from his body, only to see it dragged away by hungry zombies. He also loses his head, an act that is performed with surprising realism. Another soldier has his face torn off, and in a matter of seconds, is stripped clean of all skin and organs. The zombies then sit down for their long-awaited feast, greedily slurping on feet, arms, jawbones, hearts, and torsos. It’s a bloody, pus-filled, glorious mess.

There’s more of a happy ending this time around, as the “good guys” (all non-military) escape in a helicopter and relax on a desert island as the credits roll. But we know they will eventually die, which is the way of all zombie cinema. The acting is second, perhaps third, rate (Romero continues to insist upon rank amateurs) and most of the time the dialogue is campy, but tongues are always firmly in cheek, and the film has a sense of fun that is missing from too many contemporary horror films. And hey, I liked Romero’s take on the military mind — mean-spirited, racist, sexist, and trigger happy. It merely proves Kubrick’s old thesis that if we are ever faced with a catastrophe of the highest order, the men in camouflage are the last people we want in charge. At every turn in Day of the Dead, the soldiers mock science, seem confused by big words, and express disgust for books, contemplation, and reason. All they understand is power and death. No argument here.