Numerous critics have described Danton as a treatise on not only the Reign of Terror, but also a comment upon events in Poland in the late twentieth century as totalitarianism left the hopes of the Solidarity liberation movement in ruins. Though Andrzej Wajda as a filmmaker has been concerned primarily with Polish history and identity, the seminal work that is Danton is universal and tragically has been repeated through history in the form of absolutist rulers twisted by idealism into bloody caricatures of themselves. As the bodies piled up, and the intentions of the movement veered radically off course, those rulers rewrote their own history, carefully crafting their own reality as if hermetically sealed from the real world. Consider this film as widely applicable as Animal Farm, and without roots in any particular place or time, as the Costa-Gavras classic Z.

On its surface, the story takes place during the Reign of Terror, five years after the storming of the Bastille. The philosophy of Rousseau was a strong influence on the forces behind the French Revolution, namely his ideas espoused in The Social Contract and the sovereign will of ‘The People’ and the rule of law as authored by all people. The adulation of Robespierre and Saint-Just for Rousseau was perverted by their lust for power and the belief that all acts and intentions should be followed to their logical conclusion.

And so the will of The People became the will of a few people speaking on The People’s behalf. Any voice against the rule of law written by the Committee for Public Safety became a betrayal against the Revolution itself, and that Committee would strike out with vengeance in mind. The steady stream of bodies to the guillotine was the fuel upon which the French Revolution turned, or so they thought. Though the people involved in this tragedy were numerous, Danton focuses on the two symbolic heads of the divergence of the French Revolution: Maximilien Robespierre and George Jacques Danton.

Robespierre was an unimposing figure in life, and so he is in the film; fastidious and a hypochondriac, but also a sharp legal mind and a compelling public speaker. A leader among the Jacobins, his first demand for the death sentence was of King Louis XVI, in that if the death of one man was required to save the Revolution, then there was no alternative. This became a chorus of sorts as he became head of the Committee for Public Safety and thus the Reign of Terror began. He believed that the “terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible”, and he was surrounded by like-minded fanatics who were willing to plow forth without slowing, since there could not, logically, be a cliff ahead. Danton, on the other hand, was a more moderate among the Jacobins, he espoused Rousseau’s belief in the dominion of the public will, and was the leader in the storming of the Bastille.

His ability to shake the walls with his oratory was legendary, and his popularity allowed him to harness the insurrectionary spirit of the people. He helped set up the Committee and make its power absolute, refusing to join to avoid a conflict of interests. As the power of the Committee grew, and its willingness to use its blunt force was more gleefully applied, Danton became disconcerted with the direction of the Revolution. It had become extravagant and senseless, though Robespierre felt that such a surgeon’s knife is wasted if not cutting constantly at tissue that is or should be dead.

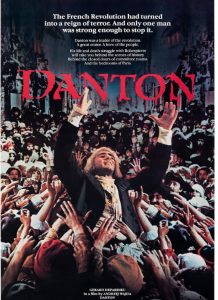

Robespierre, as portrayed by Wojciech Pszoniak, is ascetic, bloodless in human form if not in deed; he seemed not to enjoy anything apart from the satisfaction of forward momentum of the Revolution to which he dedicated his life. Danton, played by an effusive and larger-than-life Gerard Depardieu, is venal, wealthy, and brimming with the vice that signifies the flawed human as well as the humanist. Danton had an iron fist and moved the masses in the recent past, but was not willing to cure the headache by cutting off the head, whereas Robespierre believed only in the infallible logic of the revolutionary.

Danton returns from the countryside to confront Robespierre about the disastrous turn of the Terror. During the opening passages Wajda paints a bleak and dangerous Paris, using filthy streets teeming with the masses on verge of riots and paralyzed by fear. Everywhere there are spies, not because the secret police is legion, but because fear has turned every citizen of this new republic into a spy. All fear being denounced for the merest trifle. In Robespierre’s spartan household, only political tracts are read in clipped tones; cold minds bounce ideas off bare walls. The soundtrack is infused with music that can only be described as macabre, like something that would emanate from Herzog’s choir-organ, and sets the tone of a horror film. I use this term not only to describe the eerie tone of the proceedings, but because the film itself shares the structure of a horror film. You know the characters, you know who will die, and as the people are stripped of dignity and hope, you get to watch with sinking dread.

Depardieu gives one of his best performances here (every bit the equal of Jean Le Florette) as passionate, wild; he is the embodiment of the spirits of revolution and anarchy, and willing to drive Paris to explode once more. Danton repeatedly assures his followers that the people love him, he is the man of the hour, and Robespierre cannot touch him. Pszoniak gives the more internal performance, and is something to behold in a character that could so easily fall into parody. The two titans meet in Danton’s flat, as Robespierre attempts to bring his friend back into the fold of the Committee. Their personal connection is made real, and one watches two philosophical colleagues spar gently over the question of what the direction of the Revolution should be; the silent question is whether Danton will force Robespierre to arrest him and place him on trial.

The scene is ingenious, from the careful setup as Danton fusses over a luxurious feast and flower arrangements that his adversary will eventually ignore, through the confrontation where they clash in thoughtful conversation. Political platitudes give way to questions of personal and public duty, and despite the fiery diction of Danton, Robespierre is unmoved, and in his staid reserve, outmatches his former friend. For all of his energy, Danton is out of touch with the Terror, and somehow believes himself above the fray and impervious to sharp edges. And here is where the film takes an unexpected turn: a film so named Danton would be expected to side with its titular character, but this does not happen.

Though the filmmaker obviously agrees with the man, who is more moderate, human, and a true believer in the sovereignty of the public will and the laws they create, he understands the mind of the butcher behind the Terror, and that once the mind of a fanatic is made, there is little stopping it. Danton was foolish to believe that his popularity and thunderous voice would save him from a steeled intellectual mind that sees in black and white, rather than the riotous spectrum of the human spirit. The former patriot was complacent, corrupt, and careless with not only himself, but with his like-minded compatriots. Just as Stalin felt his hand was forced by his co-revolutionaries, Robespierre took the door that was left open to him. As Depardieu attests: “I’d rather be executed than be an executioner.” And so, the stage is set for a battle of wills that plays out in sickly detail.

The trial is a showcase for brilliant speeches and political maneuvers as Danton attempts to whip up opposition, and Depardieu bites into his role without leaving tooth marks in the scenery. With time, however, it becomes clear who the victor will be – though whether Robespierre can be called victorious depends on your definition. Throughout, the immersive experience is total, and you can practically smell the disease in the air. In one scene of appalling beauty, Danton and his fellow prisoners are paraded through a prison block, packed with men and women in squalor, all hailing their hero.

One prisoner, however, grips Danton’s arm, hissing his pleasure at seeing the architect of the tribunals headed in the guillotine’s direction. Robespierre never expresses disappointment or hatred of his former friend – to the end he believed that his action was in the name of justice. In the film, he is seen as somewhat moderate compared to some on the Committee, like Saint-Just, who chided him for defending Danton and delaying his arrest. They truly believed in a Paris of Virtue, and were willing to burn everything that failed to satisfy their values.

Despite his efforts during the trial, the absolutist power of the Committee holds sway, and the defendants are provided with no witnesses, the judges read from predetermined scripts, and the verdict is read to an empty defendant box. This haunted scene evokes a doomed mood, all the more powerful for its universality and clear parallels to despotic governments past and present that go through the motions of a trial. Watching this, I was struck by how easily such a scene could take place in my country if democratic ideals branded as ‘quaint liberalism’ were discarded. Of course, the military tribunals for terror suspects (who to this day are either called terrorists or ‘no longer terrorists’ – they have never been acknowledged as innocent) are run this way, with no lawyer, no witnesses, no actual charges, and the verdict and sentence are sealed. In case you ask, this practice has yet to be denounced.

The final minutes drag with a nauseous finality, and unforgettable images play forth; a guillotine enshrouded in cloth, the blade peeking out as if bored of its languor; a naked infant held aloft to watch its father marched to the guillotine, bawling endlessly for the days which will only get worse; Danton looking wildly to the sides, still hoping for escape as he is secured in the guillotine; blood soaking the straw piled underneath the platform, as if anything could conceal the event.

The portent of the climax is equaled by some of Herzog’s work in Lessons of Darkness or perhaps the endless scenes of Aguirre, looking for the flooded shores of the Amazon that are miles distant as they venture further down the river. The denouement, as a child reads the articles of freedom to Robespierre, serves to make a mockery of all that the man stood for, and of all the rights that people of democracies utterly fail to care about. The aftermath of this disastrous decision by Robespierre is not dramatized, but this was not necessary. The very walls appear painted with pure nightmares, and it is clear that the dignified men in the powdered wigs would soon be consumed by the fire they were stoking.

This dark work by Wajda is nothing short of a masterpiece of mood and a dissection of politics where power and philosophy drive humans toward inhuman ends. Massacres almost appear to be inevitable when the reins are held by skillful politicians that can move the masses well over the edge into insanity; perhaps peace is only possible when our leaders are too incompetent to create much mischief. Rousseau pleaded for a government model that is based solely upon the law as written by the people, and that those people submit to the general will, creating a civil society through the ‘social contract’ of which he wrote that stresses equality above all else. Clearly such ideas were meant for intellectuals, and arbiters of reason. In a way, Danton lays out the case for the impossibility of such a utopia; men of reason shall always fall before men of resolve. Resolve does not require thought – if anything it thrives in its absence.

When Georges Danton was executed after a brief trial, Robespierre was deprived of the only man who would defend him. “Like Saturn, the Revolution is devouring its children”, Danton noted in his trial. Within three months, the Committee for Public Safety was consumed by infighting, and the giants denounced one another as chaos erupted in Paris. Legend has it that Robespierre is the only man ever to be guillotined on his back, so he could watch the approach of the blade.