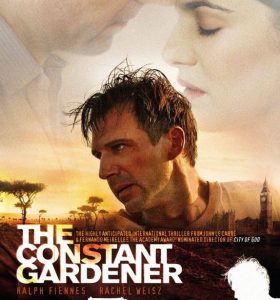

The Constant Gardener is a bloody good thriller; the sort of lean, intelligent drama with a conscience they used to pop out twice a month back in the early 1970s. And in the tradition of The Parallax View or Three Days of the Condor, director Fernando Meirelles has crafted a film that responds to prevailing winds (in this case, that corporations are evil), and yet remains timeless in its human dimensions. For while this is a stirring indictment of greed and corruption at the highest levels of power, there is also a love affair that, while flawed, resonates because it concerns the hunger of need. Justin (Ralph Fiennes) and Tessa (Rachel Weisz, Oscar winner) are hardly the perfect couple, but they each serve a purpose for the other at a particular time. And only after tragedy strikes does Justin realize the depth of his commitment, but in a way that avoids obvious sentimentality. Above all, Justin comes to respect the passion and drive of his late wife, even if he didn’t care to understand the full extent of her idealism while she was alive. In the end, he becomes the sort of man she might have applauded, even if the gestures are too late for her to notice.

And while the relationship holds up throughout (it is never simply a side story), it is the righteous anger that sustains the piece. Meirelles (City of God) is such a confident, assured filmmaker, that it seems impossible that he hasn’t been doing this for decades. He elicits outstanding, natural performances from the entire cast, and events never drag as the story moves forward, back through time, and ahead again, revealing secrets and lies, but never insisting on the element of surprise for a cheap payoff. But unlike the rage of, say, Lord of War, the disgust is never forced, believing instead that political points are far better served by a crackling tale well told. Anyone can preach from a soapbox, but viewers quickly tire of sermons. The Constant Gardener reveals a world of almost exhaustive despair, yet it never strains credibility. Above all, any thriller worth its salt must reflect a world that can — and perhaps does — exist, otherwise we are merely entertained, instead of left reeling with the pain of it all. True, I entered this film a depressed misanthrope and leave unchanged, but in this context, that’s a testament to the movies unsettling truth. If I had left with a glimmer of hope regarding the salvation of man, I would have dismissed the effort as a pack of lies. So why am I smiling?

My grin, above all, is a reflection of my admiration for cinematic courage, and Meirelles continues to demonstrate that he is not going to settle for mere distraction. He is an artist of the world, as he once again shows us locales that are too often ignored by the fat and contented of the First World. Instead of South America, Meirelles now tackles the undeniably hellish Africa, a continent so sad and bereft that it might be understandable to look away. Theirs is truly a land without hope, but this is more than a portrait of their mad descent into disease and tribal warfare. For they did not choose their other role, that of unwitting guinea pig for pharmaceutical companies and their servants in government offices across the globe.

While the movie is based on a John le Carre novel and not CNN, it has the spirit of the facts, and no one involved in this production ever tried to say that this was a documentary. But is it so hard to believe that these drug companies, so fanatically committed to the bottom line, would use Africans — the poorest and most despised of the world’s victims — as test cases for their experimental drugs? The drug in question is meant to treat tuberculosis, but its side effects are as yet unknown. But if KDH and Three Bees (the partnership that seeks to bring its drug to market) are forced to return to the lab and spend millions of dollars to perfect its pills, the potential losses could reach into the billions. By that time, the competition will have caught up, and the market share would be less exclusive. But does the drug work? And will people die after ingesting it? Perhaps, but time is money. And again, these are Africans we’re talking about here. Surely you’re not putting their lives ahead of jobs, profits, and the lives of whites? Why that would make you a bleeding heart, which at this late date is clearly the greatest of all crimes.

Tessa, through her investigative work and networking, has discovered the awful truth, which of course means that she must be murdered immediately. It all smacks of a grand, left-loony conspiracy, but who among us would deny that corporations would use any method at their disposal (including murder) to keep the money rolling in? Still, I admire the spirit of the thing, as Hollywood is always at its best when it’s pointing fingers and naming names. Holding power accountable has gotten stale in recent years, as terrorism has become the new boogeyman, but this is a return to form. If you want to know who’s fucking you over, look no further than the boardroom, the floor of Congress, or the White House. It may not always be true in life, but whenever cinema reflects the discontent of the larger culture, it rises above mere escapism. And we know we’re adhering to the rules of a lost era when the hero of the piece is also snuffed out, and there’s no real consolation that the bad guys will get their comeuppance. Here, the Africans will keep dying, and the truth will soon be spun into a web of new lies that will fade away once the emasculated press finds some missing teenaged white girl to care about.

And so we have missing files, mysterious letters, shaky plane rides, and turncoats posing as friends, but this is far from a James Bond gadget show. Meirelles is careful to keep us informed and while the pace can seem a bit frantic at times (especially with that shaky camera), he never moves ahead before we’ve made the necessary connections. And yet he’s not talking down to us, or assuming we’re too dim to keep up. He knows we’re smart, and he doesn’t want confusion so much as clarity. In a way, there’s no hidden puzzle or shocking revelation, as this is rather straightforward storytelling. Intelligent and biting by all means, but not overly fancy or stylized. I’d even throw out Old-fashioned For once, that’s a compliment.

But you wouldn’t know it by some of the reviews I’ve encountered. Predictably, a right-wing radio host in the Denver area (Mike Rosen, if you’re inclined to send him a letter bomb) blasted the film for its Ideology which means that rather than indict the ACLU, teachers’ unions, or the Trial Lawyers Association, it has the audacity to drag saintly corporations through the mud. Conservatives are the first ones to bitch about pro-abortion, pro-gay, or anti-war subjects in the movies, but nothing irks them more than cannon blasts against capitalism. It scares them shitless to think that people might start questioning an economic system that has as its major selling point the choice between thirty-five kinds of soap. Sure, Communism killed millions, but always without pretense. You were a threat, therefore you must die. Simple, clean. Capitalism kills with a handshake and a smile, and leaves you convinced you had it coming. Just like the Africans.