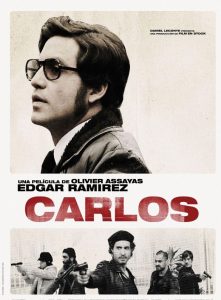

When Carlos, then known as Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, joined the PFLP in 1970, he was a radical and desired to be a solider in the international fight against capitalism and Zionism. It was not until 1975, in a raid on the OPEC headquarters in Vienna, that he discovered his true calling – himself. He was daring and charismatic, becoming a celebrity of a sort as his notoriety made his name a household word. Whereas such a strange life would lend itself comfortably to a biopic, in Carlos it becomes a study in vanity, and how the revolutionary is perhaps the ultimate egocentrist. The idea is not a new one, but seldom has it been rendered in such vivid tones. Clocking in at five and a half hours while maintaining a brisk pace and wasting not a moment of time, Olivier Assayas’s new work further solidifies him as a master of the craft. At the helm is Edgar Ramirez with a stunning performance that captures the megalomaniac disguised as an idealist, though perhaps only disguised to himself.

Carlos sticks to the meat of the man’s career, from his early days volunteering for the People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine. He staged several poorly planned jobs involving explosives and a botched assassination attempt on the Vice President of the British Zionist Federation. None of these achieved any sort of satisfaction, and it slowly becomes evident that Carlos is already an actor in his own drama. It is fun to play soldier, and he relishes the feeling of joining an international struggle to unite revolutionaries. He finally ascends the stage meant for his wily talents in the 1975 raid on OPEC headquarters, and his rhetoric is allowed to emanate from a megaphone to a global audience.

Though staged as a way to call attention to the Palestinian cause, the real purpose was to kill the finance minister of Iran and the oil minister of Saudi Arabia to facilitate the crushing of a Kurdish uprising on behalf of Saddam Hussein. How this relates to power for the people, I have no idea. Neither does Carlos, but the raid reflects his ability to solidly plan for a strike, but also betrays his lack of experience and poor grasp of who he really is. The OPEC raid is the centerpiece of the film, and though it varies from the actual event, it is made clear that this terrorist is nothing of the sort. When given the chance to die for what he voiced as a higher cause, he bellows “I’m a soldier, not a martyr!” And also a coward. Rather than execute his orders by offing the targets, he takes a massive payoff from an unspecified country and reportedly pockets a good portion of the money.

Interestingly, this reveals the inherent failure destined for armed struggle. If one’s philosophy is unable to compete with, say, capitalism without taking hostages and threatening violence against soft targets, then that philosophy is doomed. Such efforts would have been better spent coming up with a viable oppositional belief system that would win hearts and minds rather than providing fuel for angry, disaffected youths who only know they don’t agree with what is in front of them. Still, any overt point to be made in Carlos is avoided in favor of painting in tremendous detail on a canvas that spans decades and countries, allowing the viewer to make their own conclusions. Carlos is expelled from the PFLP for his failure to follow orders.

After this, he used his fame, wealth, and ability to fundraise to form his own Organization for Armed Struggle, was given assistance by the Stasi and KGB, and set up shop in Eastern Europe to attack Western targets. After seven years, pressure was applied to the nations that harbored him and his increasingly frenzied attempts to stay relevant. Finally pushed out of nearly every country left on Earth, he was isolated in Syria, and later Sudan. Surely, running guns for Sudanese butchers is for the lowest of the low.

With the end of the Cold War, he was more of a curiosity and a pathetic figure. The revolutionary can be expected to rage at the death of cherished beliefs, though Ramirez plays him as more bemused than anything. After all, Carlos was a capitalist at heart, a bourgeois twat cloaked in the proper rhetoric. This decline into obscurity is sumptuously realized by Assayas, as capitalism just outlasts such nuisances. This is not for lack of trying, but perhaps a lack of a viable philosophy to sustain any sort of movement. There is a wry sense of humor at work here; the idea that Carlos was immobilized by testicular pain when seized by French authorities because he placed a higher priority on liposuctioning his muffin top than taking proper care of his balls is hilarious.

Carlos is a wonderfully assembled work, crossing the globe with a dizzying number of characters and remaining as true as necessary to real events. The supporting work by the performers comprising the various revolutionaries who drift in and out of Sanchez’s life is impeccable, and the audience is transported into a seamless recreation of a chaotic time. As entertainment, Carlos is magnificent, with a propulsive pace and an immediacy that lends an unsettling tension to any scene with Ramirez.

Assayas leaves bare his subject, a supremely confident young man who grows into a fighter most capable of bullshitting himself into believing such conflict was in the name of freedom. One can see the seed of figures like Castro, Mugabe, or Chavez, all universally beloved soldiers for their people who became despots with a cult of personality. When the rebel – whether left or right – believes they alone hold the key to changing the world and demand that others follow, they are at the pinnacle of narcissism. The love and fealty demanded by such leaders must inevitably turn to contempt for those who give it so freely. Carlos did not even get that far. He was brought down not by enemies, but by irrelevance.