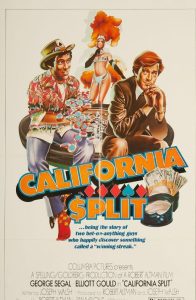

As one of the most deliriously entertaining movies ever made about the sport of gambling (and it is a sport, given the mental and physical punishment these men endure), California Split is Robert Altman at his best, complete with all of the standard features — overlapping dialogue, casual asides, random noises, and effortless, seemingly unscripted banter. Elliott Gould and George Segal star as, yes, Loveable losers, but they never resort to manipulation in order to secure our empathy. If truth is to be told, they couldn’t care less what we or anyone else might think, as they’re fevered engines of compulsion — always pushing forward in search of that next fix.

From poker parlors to the gaming tables of Reno, these two men always seem to be chasing the big score, yet even when they realize their dream, it never seems to be enough. After Segal’s big poker win against the likes of Amarillo Slim (who makes a brief appearance), Gould says, “It doesn’t mean a fucking thing, does it?” Of course it doesn’t. And why would it? Gambling, at least in terms of an obsession, has little to do with money and everything to do with feeling alive for yet another day. Why else engage in deliberate recklessness?

Listening to the commentary track, Altman said that this was one of his least plot-driven films, which is saying quite a bit indeed. Here, though, character does come to the fore more than ever, as what concerns Altman is not the big game (even though there is such a thing, taking place mostly off-screen) but the unvarnished experience of the professional gambler. Such a life is far from glamorous, but this is no morality tale, where each man comes to Jesus and returns to hearth and home after a bitter few weeks on the road. Even as one character seems broken and battered, we have no doubt that he’ll return to the same poker hall where we first met him. Again, California Split is not a downer, but an exhilarating riot; funny, observant, and alive with possibility. We encounter prostitutes, muggers, disgruntled poker players (one of whom is assaulted by Gould at the race track), dealers, and bookies. Characters enter the frame, speak their truth, and walk away again, sure of their own identity and purpose, but not at all concerned about whether or not we see all of the connections.

The wide-screen compositions are typically lush and buzzing with activity, and despite the lack of plot, we accept Altman’s vision because we’re having too much fun to care. And let it be said: Elliott Gould, now an all-but-forgotten entity, was, for a brief time, a genuine screen presence. In back-to-back Altman features (this film and 1973Âs The Long Goodbye), Gould was so engaging as to be the perfect representation of the Everyman, although an Everyman who was smarter, sharper, and more appealing than anyone else. He could size up the competition (in a great sequence at the backroom poker game), beg for credit from the cashier, attempt to use a Milky Way as an ante, and play nickel slots with all the gusto and seriousness of a master gambler, all without seeming forced or obvious. Segal is more desperate, while Gould is the sort of man who would (and does) laugh in the face of an ass-kicking, and argues — persuasively, I might add — with a gunman in a casino parking lot. Now this is a man I’d like to have at my craps table.