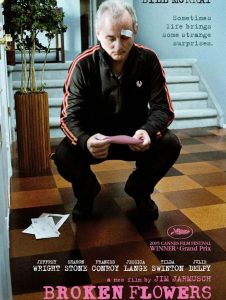

While I enjoyed the film more than I expected, it is one of those middle-of-the-road movies that makes it damn near impossible to review. Had I gushed like a schoolgirl, the review would have written itself, and the submission a mere formality. Had it been obnoxiously cloying or hipper-than-thou, the process would have been one of glee, for there are few pleasures in life as inviting as dismantling failed ambition. Instead, Jim Jarmusch has crafted a solid, occasionally elegant piece that wanders about without direction, but overcomes its weaknesses with a quiet power. Good, but not great; charming, but often maddening. I liked it well enough for a goodnight kiss, but I won’t be inviting it upstairs.

Starring Bill Murray, huh? I imagine he’s dry to the point of near absence?

With each new film, Murray dials it down with such unrestricted ease that he’s all but channeling Buster Keaton. I half expect his next role to be a mere headshot. Murray has mastered this technique — the sly nod, the slightly arched eyebrow, the comatose double-take — and he’s better than anyone else at looking as if he can’t even be bothered to get up in the morning. Here, as one Don Johnston, he’s typically non-plussed, and there’s little to criticize in the approach, but it keeps us at bay when, I suspect, we’re supposed to be drawn closer. He’s a boring man, but only because he’s equally self-involved. And yes, he’s confused for Don Johnson not once, not twice, but three eye-rollingly predictable times.

So why make a movie about him? Shit, you’re dull as dishwater and I don’t see filmmakers knocking at your door.

True enough, but where Johnston is wealthy and wry, I’m simply poor and humorless. The story, as wafer-thin as it is, concerns Johnston’s journey to discover the author of a strange letter he receives from an ex-lover. It seems that 19 years ago, Johnston fathered a child and while the identity of both mother and son remain a secret, this mystery lady, well, just wanted him to know.

A road trip? Can’t Americans learn about themselves any other way?

No, even indie filmmakers seem to have internalized the belief that if human beings are to acquire much-needed life lessons, these activities can only be pursued behind the wheel of a car. While such conventions can be annoying, Jarmusch breaks the mold slightly by insisting on the avoidance of dramatic closure. Don meets strange folks along the way (what, you were expecting the colorless and the bland?), but the conversations between them fail to reveal much of anything — at least on the surface. We can see Don taking it all in, but how he interprets his “findings” is between his mind and the passing breeze.

These ex-lovers he encounters — the usual assortment of nutballs and whack jobs?

To an extent, yes, but not nearly as heinous as other recent efforts in the independent world. Don’s first meeting is with Laura (Sharon Stone), who is somewhat normal, although she makes her living by arranging people’s closets (as so many do). What’s more, she has a daughter named Lolita, a hot young thing who just happens to walk around in the nude, although from Don’s reaction (or non-reaction), she might as well have been wearing a muted pantsuit. Don then meets Dora (Frances Conroy), who seems to have a happy marriage, but masks a deep loneliness (and something to do with being barren, as if being child-free were anything but a cause for celebration). Next up is the weirdest of the lot, Carmen (Jessica Lange), who is a kooky “doctor” who just happens to communicate with animals and translate their messages. Jarmusch doesn’t force the quirkiness, but it’s locked in place nonetheless. I mean really — doesn’t anyone wait tables anymore? Even a two-bit prostitute would suffice, as at least it has that “world’s oldest profession” thing going for it. Carmen maintains a calm demeanor, but she too has a bitter rage just below the surface, which makes us wonder what Don did to leave these women so shattered. At last, Don visits Penny (Tilda Swinton), a ferocious piece of white trash who seems to be the most likely culprit, but whose actions leave Don just as empty-handed. No prizes for guessing that Penny has trashy kinfolk, who, while working on a car, intimidate poor Don and yes, even throw a punch.

If Don is as passive and bored as you say, why on earth did he undertake such a journey?

He protests at first, but eventually succumbs to the pleadings of his crazy neighbor Winston (Jeffrey Wright), a wannabe mystery writer who takes it upon himself to examine the letter, research Don’s ex-flames, and reserve his hotels, car rentals, and airplane tickets. As presented, Don most likely would never go, even with such a friend in his life, but there must be a movie, so we are forced to accept the result. Winston is the film’s true weak link, as he’s the one character who deliberately plays it for laughs, and is so bizarre that we have a hard time believing that Don would have ever struck up a conversation with him to begin with.

So does Don learn about himself? Does he become, as the saying goes, “a better man?”

Thankfully, no, although the conclusion is sufficiently open-ended to keep us guessing. Don finally meets a young man who could be his son, but once he enters that realm of conversation, the boy runs away in confused disgust. Soon thereafter, Don sees a chubby teenager in a car that could also be his son, a possibility made more plausible by the fact that he’s wearing a similar jogging suit. But that’s the point, I believe. Don has been affected in that, in his own way, he’d like to meet his child, but rather than melodramatic tears and gnashing of teeth, he appears doomed to see the boy’s face wherever he goes. Don might return to his abode and sleep away the day once more, but the seed has been planted, against his better judgment. And, in one of the film’s stronger elements, it remains possible that the initial letter was a fraud or even a cruel prank. Perhaps Don will never know.

It still seems pretty thin. Anything else to recommend?

Story and character aside, the film has a leisurely pace that I always find endearing, and the relaxed, jazzy soundtrack is impossible to dislike. And I’m always partial to a central character that does little to garner our sympathy or concern, even if those very qualities keep the film from being completely satisfying. It’s that eternal dilemma: we want to be respected enough to figure things out on our own, but the less we have, the harder we strain for emotional involvement. I can love a bastard, after all, but I’m dangerously close to indifference when confronted with a cipher.

So did you love it or hate it? What the fuck?

If my overall response is confusing, that is how it should be. This is a film that would very easy to dismiss, but Jarmusch won’t let us go without a fight. We keep watching not because we expect fireworks or even answers to questions that may or may not have been asked, but rather out of a sense of obligation to a filmmaker who always seems on the verge of total confusion. We expect one thing, get another, and where we want highs, we are given lows. Perhaps only later do we realize that we were always in wiser hands.