Time and again, the cinema validates the old adage that no greater bore roams the earth than a poet scorned. Such a man inevitably spends the better part of each aching day stalking through high grass, brooding in trees, and wishing he were any number of ephemeral insects, most often the dizzyingly beautiful, though largely misunderstood butterfly. He is a man of modest means, living with generous relatives and patient friends alike, inhabiting whatever couch will receive him, provided it not ask for suitable reimbursement. If he’s worth his salt, he is proud, largely unknown, and most appreciated by a singular voice in the wilderness; a woman, herself striking a note against the raging current of the time, who pines with equal solemnity and well-earned tears.

If you are John Keats, at least the Keats imagined by Jane Campion, you are the proverbial doomed romantic; the sort of man who falls in love not simply with his heart, but through every pore, corpuscle, and follicle at his disposal. And, as if on cue, he will sulk about the soggy streets of London sans coat, develop the only real illness required of him (in that it involves copious coughing fits and assorted blood-stained garments), and die off-screen as the fairer sex wails with righteous self-pity. It’s exactly the sort of bilge the awards season was calling for.

There will be the usual high praise for the cinematography, costumes, and orchestral lushness, which, of course, is the surest sign that the story itself isn’t worth a damn. When the volume of defense deafens upon discussion of furniture or topcoats, yet fades to near silence when matters of plot and character rear their heads, you can rest assured that the film in question would have been better conceived as a museum piece. Audiences do in fact exist for movies that remind women of how their husbands do not similarly speak at any point during the day, but it continually astonishes that this number is sufficient to secure the necessary investment.

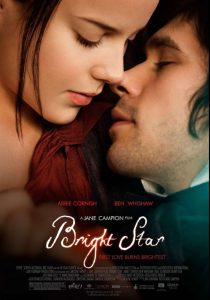

But here we are, yet again, bearing witness to moon-eyed lovers who seem to have found that one precious acre of life that asks not a moment of hardship, sacrifice, or actual work save falling to the floor at one of two eventualities: the arrival of a heart-rending letter, or the next unendurable day without one. Miss Fanny Brawne (Abby Cornish), is just the woman for the task at hand, and she tumbles to her knees on no less than a dozen separate occasions, once insisting that there must be an afterlife because no God would ask us to suffer so greatly in this one. Mighty words indeed, made slightly less than palatable by the sort of heroine who takes a nap to relax from needlework.

Fanny is a fickle, hopelessly irritating young woman, which makes her the ideal companion for the world’s most self-involved wordsmith. He’s a genius by implication, which means others sing his praises at every turn without actually having to prove it. Far be it from me to deride the sainted Keats, but surely more evidence exists than his propensity for pensive stares into sunlit landscapes. From what we do hear, he is a man singularly obsessed by his own mortality, which — based on the performance by Ben Whishaw — avoids the universality of the experience in favor of typical navel-gazing.

And let’s face it: the love imagined by these masters of the quill has never existed at any point in our history, proving yet again that poetry endures because it fosters our basest delusions. The human experience is about the becoming, not the present, and few seem willing to put the daily incivilities of life between two perfume-scented covers. Keats and Brawne practically inhale each other’s narcissistic aroma like pigs feeding at the trough; disabled not by the other, but rather the idea that passion is the only worthwhile endeavor. To hell with common interests, wit, or any semblance of lasting connection. Apparently, one can dine on merely speaking about affairs of the heart, rather than putting it under the microscope of actual doing.

Again, this is nothing more than a two-hour death watch; a numbing, dramatically inert exercise in how to slow time to a crawl in order to show that the world kills its creative class with malice and great cunning. Tossed about are the usual rages of a girl in love — that she alone has felt this deeply, and that their different stations should not block their marriage. They can’t really tie the knot, of course, because what poet could ever settle down, and this Keats fella, why, he has the bearing and heedless hairstyle of the true rebel. He’s even unshaven in that way that takes weeks to perfect, and is not above insisting on a lock of hair for his doomed journey to Italy, the very place that will receive his willing corpse.

He dies young and obscenely good-looking, helping to avoid an old age that would have revealed any number of weaknesses and annoying habits. As conceived, his entire being is simply pouting lips, soft hands, and words to reduce to the womenfolk to weak-kneed compliance. My god, he even has the power to envelop burly poets of a heterosexual stripe, in this case one Mr. Brown (Paul Schneider). Brown is more alive sitting down than Keats in the whole of his appearances, yet no one thought it wiser to send the story his way, I’m guessing because his anonymity renders him unfit to carry the load of a feature film. At the very least, Brown is more nuanced and alive; a complex figure of regret, insecurity, and contradiction, while Keats remains a single-minded creature of lovable martyrdom.

Such pious nonsense sends me into a melancholic rage, and one can only leave Bright Star with the hope that the motion picture business will soon tire of using the artistic temperament as a model for the richness of experience. Here, the romance is all on the page, and if Fanny was in fact a muse, she was so only by the power of her unencumbered breasts. Mr. Brown had her pegged — her interest in literature and poetry was a ruse to secure affection — though this insight was but a cover for his own quiet longing, which is yet another tired cliché deserving of swift burial. Visual beauty, in life as in a darkened theater, excuses even the most heinous of crimes, and sheer nonsense, by virtue of a painter’s touch, is imbued with wisdom, fire, and the rush of great splendor. It’s the expected con, as empty and shallow as the very message it sees fit to feed to a hungry audience. Live for love, and die trying. It’s the poet’s way.