1969. John Landis is a kid on his first movie set, just out of school and bushy-tailed for adventure. The studio sends him to be Ninth Asst. Director Once Removed on a war film in Serbia, or Albania, or Montenegro—one of those gray, superstitious countries where the entire population is wrinkled old women, swathed in black, eating tripe-soup because ‘it geeve you strengss over ze day-vils.’ He had to go out into the sticks to get-some B-roll and they send a fixer with him to make sure the little Jew didn’t come ‘crosswise of a misunderstanding’.

There was a long dirt road that bifurcated the country, some four hundred miles, it cut through the back country and while he and his fixer were being jostled in their tiny Iron Curtain car, they suddenly had to stop. Why? Because there was a pack of gypsies in full regalia burying a man in a narrow hole, feet down and trussed in strands of garlic.

The fixer, whom Landis assures had many war crimes to his credit, was in hysterics laughing at the backwardness of the gypsies. Burying a man vertically at a crossroads so he wouldn’t get up later and cause trouble—that’s how they put it, ‘so he wouldn’t get up later and cause trouble’. And while this button man of the local mafia (no doubt) laughed his ass off, Landis had a thought, a rebuke for his handler: What if the dead man actually did get up? How would he react to that? Where would his mocking laughter go when fingers pushed through the loose soil, followed by a hand and an arm and that arm pried the dead from his grave? Wouldn’t be so cocky then, would you, Sasha?

That was the inspiration for American Werewolf in London.

A year later there was a script and Landis got a lot of work from it, but no one would dare make it, as they explained to the ambitious boy, it’s too funny to be a horror, it’s too horrible to be a comedy.

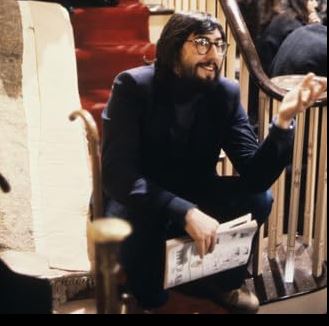

Landis starts directing his own low budget movies, like the movie Shlock! a send-up of rubber-mask monster flicks ala Trog! And he starts hunting for make-up men on the cheap, someone fortuitously points him in the direction of a young savant who lived on scraps and worked out of his apartment and slept on a fold-out sofa: Rick Baker.

I’m sorry, I got the name wrong, let’s do it again, pick it up at ‘young savant’:

…a young savant who lived on scraps and worked out of his apartments and slept on a fold-out sofa: RICK ‘MUTHAFUQN’ BAKER.

Cuz he was a ‘fuqn’ genius and he was the key to American Werewolf in London. Without Rick ‘Muthfuqn’ Baker the movie would’ve been great because Landis wrote a great script, with Rick Baker on board Landis’ great script became a timeless cinematic masterpiece.

1980. Landis made his bones on rent-check productions like Animal House, and The Blues Brothers, little films with low commercial success that no one but cinephiles have even heard of, but despite their limited appeal and brief shelf-life, these art house offerings gave him just enough leverage to call up favors for his passion project: a werewolf film he thought up while watching gypsies bury their dead.

He was, before meeting Rick Baker, perfectly willing to make this movie with a 1930’s Lon Chaney werewolf that was just a static hair-ball who transitioned from man to monster as one transitions from 39 to 40 years old, with a deep sigh sitting in an armchair—but now that he knew Rick, he had plans, baby!

Puh-lans!

But make-up and special effects aren’t story and Landis wrote a script brilliant in its modernization of the wolfman, innovative in its humor and graphic in its violence, it casts a deeper psychological torture on the wolf, not merely dread at becoming a ravenous man-eater—which is the desperate motivation of most movie wolfmen–but being mentally tortured, preceding that transition, by demonic dreams and the very real torture of meeting your undead victims who must walk the Earth in limbo until you die.

One of them being your best friend.

David Kessler and Jack Goodman are Americans., we first meet them hitchhiking through the moors of North England…

…in a truck filled with sheep.

Yep. The opening metaphor. Subtle as a brick in the face. And if that wasn’t portentous enough, they happen upon a creepy pub called ‘The Slaughtered Lamb’. In the pub are a bunch of locals, icy to the newcomers but, they warm up after a few American jokes, then they turn to ice again when Jack Goodman asks why they have a friggin’ pentagram on their friggin wall!

The look on their faces are like the people in your pew after you rip one in church.

So they decide to leave, unlike you, in church, and you opt to look in the same direction as them as if that bench-rattler came from the old lady near the aisle. Gross old lady, doesn’t she have any respect?…right fellas?…doing that… in God’s house…all willy nilly? Shame on her.

Before they go, they give the lads some fascinating advice, “Stick to the road. Stay clear of the moors. Beware the full moon.”

Why, thank you kindly, shifty bar patron–we, uh, shall, um, do that.

But they don’t. In the rain they wander into the outback and the start hearing howls, then growls over there, then over there. Whatever it is, It’s circling them.

In positively the best jump scare of the last fifty years, a snarling ball of hair and teeth shoot into frame and in a series of shots that damn near got this movie an X rating, you see the legitimately terrifying and gruesome murder of Jack Goodman, his face and chest torn in such a horrible way, even now I can barely watch. After a lifetime of thinking about it, now I know why it’s so disturbing to me, it’s the piercing screams of Jack that make it so horrible. David, for his part, ran, then thought better of it and ran back, only to get mauled. But just as the monster gives a trio of rips, the creepy bar patrons show up and shoot it.

Before he passes out, David looks over and sees the beast, but it’s not a beast, it is a naked man he’s never seen before.

It’s these isolated moments that, in the aggregate, create the cinematic masterpiece I mentioned, Griffin Dunn (Jack) made me, and a scared-shitless generation of adolescents, believe he was getting ripped to tinsel. His screams came from his soul, and I heard them in mine.

Likewise, John Landis directorial restraint, by keeping the truly awful visage of the monster just out of reach, just a brown blur,, it quadrupled the horror of it.

Here’s where we get into the traditional story, Kessler wakes up in the hospital, is told his friend is dead, it’s been three weeks, they were attacked by a ‘madman’ who was killed by the villagers and everybody testified that’s what they saw and it wasn’t an animal or a monster and his memory is wrong. He’s looked after in the hospital by a RAVISHING Jenny Agutter. I don’t know how to describe Jenny Agutter; she’s beautiful, but not beautiful in a delicate, leave-it-alone sortofaway, she’s beautiful in a –and how do I say this without seeming like a pig– oh, she’s beautiful in a way that has you seriously consider the pluses and minuses of daylight sexual assault.

There, that was classy.

Jenny Agutter is so beautiful, and her Florence Nightingale, single-girl-in-the-city sexuality so very present and seemingly accessible, it makes it so she’s still a candidate for rogering now, present day, nearing seventy years old.

So the wolfman now has his woman—a very necessary part of the werewolf legend—the optimism of new love, balming the pain of losing one’s best friend.

“Can I have your toast?

CUFFA-WUPPA-BIZ-BONG! JACK?!

Torn to shreds, wearing the same clothes he had on when he died, Jack Goodman is there and now tells David about the un-dead souls that must walk the Earth until the bloodline is severed and that means David killing himself.

And here is where the genius of Rick Baker first shows up, because as he stands in David Kessler’s hospital room, Jack’s wounds are positively stomach-turning, his face is ripped by claws, his neck has been torn out, his gortex coat rendered into strips. He is disgusting to behold, but he is still his friend and dammit it’s good to see him.

But seeing your friend decompose in front of you is only the beginning of David’s passions as he is now plagued with vivid nightmares of murder and Nazis and his family being butchered and the pretty nurse being murdered and him running through the woods naked eating deer…not your standard ‘I’m back in school, and I’m in my underwear’ sorta nightmare.

Pretty nurse does what we’d all want the pretty nurse to do, take sexual pity on our trauma and bring us back to her apartment for a medicinal boink.

Jack, you’re back! Let’s leer at the pretty nurse and forget how weird it is that I’m lusting after a girl with the corpse of my best friend. Again, Jack warns him that tonight’s the night, bro! To which David is, like, I don’t believe you cuz you’re dead, to which the dead guy says, then expect me back, Fido, and I’ll be bringing friends, and David’s like What friends? And the dead-dude is all, I won’t know till you make them for me.

Meanwhile, the doctor that treated David is taken aback by his story and investigates the creepy town with the creepy pub with the creepy patrons and the creepy star on the wall. And he notes how creepy they are, as a people with creepy secrets are wont to be, until one of them decides to end the madness and confess. The doctor thinks it’s just a collective obsession and if David is convinced he’s a wolf it’s because these people believe he’s a wolf. That’s all there is to it, see? Just a little contagious delusion that makes a healthy boy writhe on the floor that night and grow hair and fangs…delusions are more powerful than you think, the socially suggestible are known to regularly deform their skulls into that of a canine snout, just on peer pressure alone.

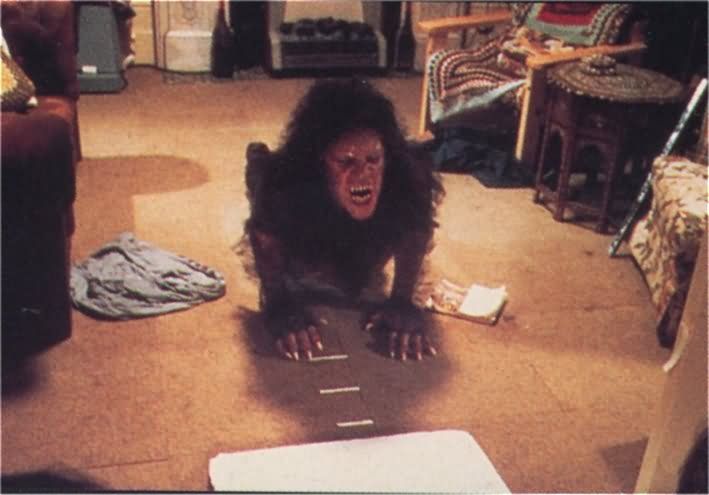

Now for the scene. This scene is what made the movie a masterpiece, not just good and not just great. The transition scene. In the nurse’s apartment, while she’s at work, and he sits reading, we hear the pleasant sounds of ‘Blue Moon’, then

“JESUS CHRIST!”

That’s how it starts, ironically calming music, David’s reading all contented-like then from nowhere he screams ‘Jesus Christ’, hits the ground, says he’s burning up and starts taking his pants off. And from here on it’s pure Rick Baker.

First thing: no horror lighting, no shadow or fog to give the make-up man a break, nope. Full room illumination.

The transformation takes two minutes of screen time but it took two weeks to shoot and got Rick Baker the VERY FIRST OSCAR for Make-up and effects EVER!

Here’s the shot list:

Hand grows. [And not how’d you’d expect, it grows in the most painful way, from center density upward, the sound design is also expert, filled with tiny ripping and cracking sounds.]

Feet Grow. [Again painfully, while on his knees, the toes pressed against the carpet, the feet grow vertically from center mass, the heel becoming the backward hock (ankle) of a dog.]

Hair grows. [This was done by punching hairs through the fake skin and the pulling them out, then showing the film in reverse. A Rick Baker Original. Also, the raised bumps of the spine popping up to the obvious foley sound of someone crushing a paint can under a car tire, and it really makes you feel it.]

Fangs, Nails, Torso. [He’s getting hairier with every shot and in every shot his teeth become longer and sharper as do his nails. He flips on his belly and by use of a false floor, Rick Baker operates the puppet of David’s lower half, stretching painfully, again from center mass, like a square of taffy.]

Face. [This one messed me up as a kid, we see the screaming face of David and then his mandible and upper jaw just pop out, nose warping into canine slits. Again, this is in full sweaty light, no half shots, in close up. Lon Chaney can kiss Rick Baker’s ass.]

Every flesh twisting, bone-cracking second of that transformation made you doubt the existence of a loving God, and it was Genius.

But the Genius didn’t stop. John Landis showed you the beast David became at 70% completion, this is not a jip, there were horrors to come, but horrors shown in flashes of the full beast at his brutal work.

What follows is the wolf’s first full night on the prowl, and the best of horror pacing follows as innocents get sifted for their fatty bits. The standout and most terrifying victim being a man in the London Underground. Remember, Landis wanted bright source light in the belief—the true belief—that it would amp the horror. Exhibit A, your honor.

In a perfectly abandoned, late-night subway platform, a man is pursued by–as far as we’re concerned–the sounds of growling. He trips and stumbles, loses his briefcase and collapses on an escalator that slowly brings him up, and we see, down, over him, in a far shot, the beast slowly walks into frame. Just for a split second.

It is positively the most lonesome, desperate feeling of oh-shit! possibly produced in a two-dimensional medium. I could name other movie moments that were its equal, but none that were its superior.

The next day, after waking naked in the zoo and stealing a little boy’s balloons to cover his nakedness (the funny moments are real, you kinda understand those early producers who said it was too funny) he seeks out his girlfriend and in so doing overhears that a bunch of people were murdered.

Here we get a werewolf trope, the ‘I’m-a werewolf-lock-me-in-jail’ scene which is always coupled with the common ‘I-think-you’re-a-crazy-person-go-away-now’.

The full moon last two nights and in one of the better idiosyncratic John Landis touches, the movie culminates in a porno theater showing a movie called ‘See You Next Wednesday’. This movie lives in the Landissphere as the only movie that ever gets advertised or displayed in poster-form or splashed across a billboard. He honestly expected no one to notice it.

In the porno theater, Dead Jack shows up, distinctly worse for wear, and they discuss his suicide, and he brought some aforementioned friends, the ones David made for him, his victims from the night before. All eager for him to wack himself right there.

Cue second transformation, almost all off-screen, wolf breaks out and goes on a snapping, man-ripping rampage near Piccadilly Circus. Police+Dark Alley+Pretty Nurse=tragic ending with ironically peppy song. (I don’t think that counts as a spoiler).

This isn’t a ‘Highly Recommend’ it’s a ‘How Dare You’ if you show excitement for this movie shy of ejaculation. I would hunt you in your pajamas over un-even ground if I discovered you willfully ignored this movie—all John Landis movies are gift to popular cinema, but this movie is a gift to the CONCEPT of filmed horror—and I hate horror! His script single-handedly retold and made real the terror inherent in the werewolf legend that had been lost by bad re-tellings. The whole reason it was scary was lost on the audience, the werewolf has always been a sympathetic and tragic figure, but Landis reminded us why.

The werewolf is a metaphor for male sexuality and coming of age, the fear of a young man as he transitions from weak boy to testosterone-laden monster. The werewolf is scared for everyone else when he realizes his potential for destruction, the pain he would create when he sees the full moon (a feminine symbol), the cloud slipping away from it, leaving it bare and exposed and the madness takes over. He becomes something he doesn’t want to be while loving what he has become.

Landis subtly made us remember our own tragedy, because we are all werewolves, or we’re the pretty nurses in their path, either way the werewolf legend is there to warn us: When your boyfriend tells you to get away, you lock yourself in the bathroom, curl up in the tub with a rosary and hope a whiff of that Guatemalan maid is enough to lure him off your scent. Which is what they used to teach in schools, you know, before Obama got his hands on everything.

Leave a Reply