Agora seems almost perversely designed to avoid a larger audience, as it is a defiantly intellectual and bold work that meets the great war of humanity head-on; this is the eternal battle between knowledge and superstition. This war has been waged since before the idea of singular deities, and will continue to burn as long as we remain tethered to this lonely and indifferent planet. The big draw of superstition is that of comfort; one disregards the potential danger of discovery and the responsibility of understanding in favor of assuming a chosen ‘truth’ and need never grow. It is attractive, and so has taken the world by storm in various guises from religions both pagan and monotheistic, to ‘spiritual’ philosophies, to the present-day political dogmatism from neoconservativism to fascism.

All share a lack of interest in information or ongoing learning, while requiring unquestioning adherence from their followers. The charlatan creates a reality and trumpets it to an ignorant but willing flock; a predigested meal that will never sustain. Knowledge, on the other hand, is a pain in the ass. The acquisition and development of knowledge requires basic research, scrupulous source verification, and a ton of work to organize and characterize findings. This is expensive, requiring massive funding and entire professional specialties to nurture, regardless of the academic endeavor. Religion, propaganda, and philosophies are easy, cheap to maintain, and require only tradition to endure. Worst of all, facts newly unveiled are by nature upsetting to the status quo, as they change the rules so existing.

Revelation of a center of the universe other than the Earth led to threats from the Church for the astronomers who found them; decoding the mathematical proofs behind the Big Bang led to a sea change in how people viewed the origin of existence and religions took this as an insult. Though sometimes exhilarating, facts are painful to humans, who are by nature into predictability and routine. Still, a handful of essential scientists have labored through the centuries to drag the rest of us into our present society, though they are still loathed by so many who pine for the comfort of ignorant bliss.

Agora accomplishes the difficult task of addressing such a massive subject with a combination of intimate moments and epic panoramas, with an eye fixed upon Alexandria in the fourth century A.D. The pagan cults reign, but are troubled by the rise of Christianity, a religion which had only recently been unbanned. Jews complicate the mix as they live in smaller but visible numbers while carrying the blame for executing someone thought to be Christ. The Christians are a strange lot – loud public displays about their just and jealous God who enables everything his followers do. Several of these men have outsized ambitions, including Cyril, who sees here an opportunity to entrench Christian powers with the help of fanatics.

One in particular, Theophilus, is a charismatic individual with the gift of public performance. Walking on hot coals and ridiculing pagan priests wins him converts, while handing out bread wins entire crowds. The pagans are overconfident, and feel this new upstart religion will burn itself out with time. The leadership, leftovers from the dying Roman empire are pagans as well, but converts rise among them. Theon, the curator of the Library of Alexandria, is slow to realize the growing threat of these men who preach forgiveness but carry knives. Amidst this tumult, his daughter, Hypatia, is the even and calm center of the universe.

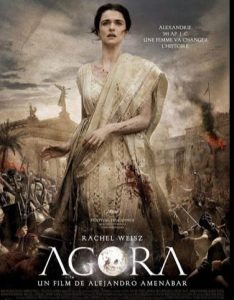

As played by Rachel Weisz, she is confident in the ability of tireless questioning to find all solutions. Unmarried, and with no intention of ever marrying, she captivates the men around her despite her asexual presence. These men, all students and a slave, form the remaining framework of the story that truly is epic in scope. They go on to fill positions within the social elite, including the government and Christian bureaucracy. The center they revolve around is an enigma to them.

Hypatia is a thing of beauty, of intellectual rigor as a renowned mathematician and astronomer, and of power as a teacher of the first order. Initially her gender is not considered a problem since she is protected by the pagans and her father, but this changes with upheaval. An Agora is a place of public gathering, where fanatacism tends to have its greatest victories. In one such Agora, Christians are gathering to insult the pagan Gods there in the statues. The pagans reply with violence, only to find the shadows are filled with new adherents to the faith they thought was on the periphery. This scene, brutal in its impact and breathtaking in scope, is one of the best battles ever filmed. This captures the embryonic beginnings of such terrible events, the way it grows in scale, how the fight gets out of control very quickly, and the turn of the tide forever.

The camera varies from street level shots with blood and guts to overhead shots that truly give a sense of another entity watching the proceedings. Finally, the camera pulls out to the entire Earth, lending the moment an uneasy perspective. The climax, the sacking of the Library of Alexandria, is a tragic depiction of the loss of knowledge. At that time in history, this Library may have held up to a million scrolls containing a record of just about any intellectual endeavor at the time. Hypatia desperately tries to rescue a few of these priceless documents; most were lost. The orgy in this scene is sickening to watch if you value knowledge. If you do not, perhaps you will join the mob. The burning of a library or books is a glory to God – any god will do. It is a magnificent centerpiece for a film filled with ideas.

Strangely enough, this was not the focus; the destruction of the Library (one of at least four times this has happened) is only a stop along the journey, as though somehow things could actually get worse. It was only a building, and though the loss of the ideas of philosophers and scientists was catastrophic, at least the philosophers were left alive. The painful second act deals with the capitulation of the government and the move by Christians to control this city, one of many. First, one must force the elite and outsiders to swear allegiance by fear. The rest must die. I cannot recall ever seeing a film where the Christians were the villains, but this work seems to pull no punches.

Still, that the reign of terror is being conducted by Christians is irrelevant; the Jews were just as capable of murder, and the Muslims that followed would be capable of the same. All that matters is which has the PR skills to end up in the majority. With this strife in progress, there seems little room for creative thought, and so it comes to be. Hypatia represents the rational as an unapologetic atheist who is consumed by learning. While the savages plan her murder, she looks to the heavens and deduces from the appearance of the sun through the seasons that the Earth moves around the sun – in an ellipse. She does not run, nor does she consider it. There is no reason to run, since every city in the world has its own struggle with insanity, and they generally lose.

The characters are thankfully allowed to be complex. Orestes, one Hypatia’s students, lusts after his teacher; eventually he becomes prefect of Alexandria as it is to be overwhelmed by the Christian mob. He exhibits some aspects of pragmatism and the ability to compromise; he remains attached to Hypatia and she is a valued advisor. Synesius is a peaceful Christian who becomes a bishop of a neighboring region. He also values the teachings of Hypatia, but seems to have learned nothing about critical thinking. Davus, one of Hypatia’s slaves, also plays a strange role of inert frustration due to his attraction to her, the impossibility of consummating that desire, and burying his thwarted hopes into becoming a religious convert.

Consider him representative of the one-issue swing voter, easily swayed by base desires into going against his better nature. The most complicated role is reserved for Hypatia, who spurns a life of her own in favor of being a teacher, and obsessed with the puzzle of the solar system. Though she is the oft-ignored voice of reason between the groups bent on massacring each other, she has her own blind spots. For example, she owns slaves, and only frees one because of a creepy incident. Owning slaves was a common and accepted practice, but her attitude is no less harmful to the slaves in her keep. The complex stew of characters makes it difficult enough to see how this monstrous tale plays out, though we may have some idea. Her feelings on religion are made all too clear as a bishop questions as to why she cannot swear allegiance to the Christian faith.

“You don’t question what you believe. I must.” A more heroic statement than this is difficult to come by.

The greatest strength of Agora is the skill with which we are placed into a time and location that is alien to us, yet remains as relevant as a newsfeed. We are engulfed with details in how classes are taught, the way religions interact, the details that are surprising or shocking, yet cast a shadow to the present day. The Parabalani, the monks charged with safeguarding the moral laws of Christians by killing anyone thought to commit sins, have their equivalent in today’s Sharia courts or perhaps Pat Robertson’s calls for terrorists to bomb San Francisco.

Theophilus gives a monologue in which he goes through some extraordinary mental gymnastics to explain how one can be a follower of Jesus with a heart full of forgiveness, and murder in Jesus’s name. It helps to be flexible with one’s own morality while being inflexible with that of others. In one scene, after Jews retaliate after being attacked with stones, a pogrom is born; a proud tradition for the next sixteen centuries, and the aftermath of retaliation a mirror of Middle East current events. Interestingly, Hypatia’s studies are often framed by violent upheaval outside her walls. Perhaps a commentary on the desire of humans to learn and discover that shall last beyond our deaths, or maybe the indifference of intellectuals to threats against their worldview. Throughout, this is a playground of ideas and philosophies literally at war.

This should be a complete mess, but the director holds the work together in a labyrinthine story that weaves these disparate threads together with no loose ends. One is allowed to see and understand all sides. Though the deeds of Bishop Cyril and his violent followers chill the heart, the audience is allowed to understand how such fatal ambition is born and fed, and why such movements sweep the world. Though such events as Nazi Germany or 1994 Rwanda seem impossible in civilized society given enough distance, works such as Agora make sense of them. These were civilized societies once, at least no more or less than ours. It is the intellectual class that holds the barbarians at bay.

This is a dense and complicated work; one of the most daring that has graced the screen this year, or indeed any year. Alejandro Amenabar has crafted a stunning work that exults in the power of intellectual works to transcend the hateful acts of ignorance, while acknowledging that the tide of superstition is as great as the oceans. The war continues.