At the age of nine on my British junior school’s playground I first became properly aware of a place called Australia. I grabbed the satchel of the rather unpopular Andrew George and started to run off (probably because I knew it contained a bag of pickle onion-flavored Monster Munch and a bottle of Ribena) when he yelled: “Dingo took my baby!” It was such a weird thing to shout that I stopped, threw the satchel in his face, and demanded to know what the hell he was on about. Turned out there was a huge news story going on about some Aussie family who’d gone camping near Ayers Rock only for some kind of outback mutt to dip into their tent and have it away with their sprog.

However, plenty of Aussies didn’t believe the mum’s anguished cry of dingo!, preferring to insist she was a religious nut who’d killed the kid herself and buried it in the desert.

Gee, aren’t people swell?

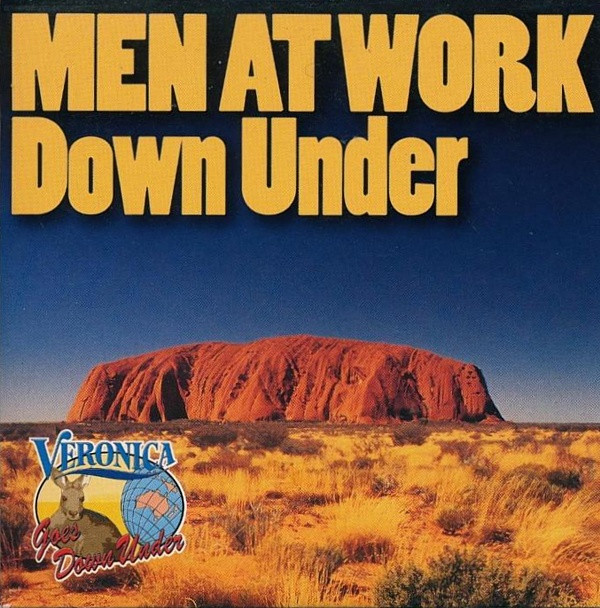

A year later Men at Work hit number one with their extraordinarily memorable Down Under, leading me to do a damn fine hopping kangaroo impression in front of the unimpressed Tracey Sharpe at the end of year school disco.

Australia, it appeared, was worming its way into my head.

About five years after Men at Work imploded, I went to see Crocodile Dundee at the cinema with Tracey, an experience that was both tormenting (she wouldn’t let me put my arm around her deliciously bare shoulders in the darkened Odeon) and eye-opening in that this faraway place called Australia was suddenly brought to vivid, big screen life. Fucking hell, it looked cool, a lot nicer than the post-cinema experience of standing in the blustery bus station with chip wrappers and dead pigeons swirling around our feet.

Anyhow, Dundee was my introduction to Aussie cinema and it wasn’t long before I started gobbling up such distinctive classics as The Road Warrior, Wake in Fright and Walkabout. Sadly, since arriving in the country (somewhat disappointed that Tracey wouldn’t tag along) those glorious moments have become much less common with the majority of Oz’s output becoming as distressingly PC and bland as everyone else’s. Mind you, although there’s not enough quality fare (like 2005’s dread-inducing Wolf Creek, the in-your-face Romper Stomper and 2011’s bone-chillingly nasty Snowtown) and far too many flicks revering Aboriginal culture as whitey plods through his racist schtick, a little digging around can still manage to unearth some Vegemite-caked, celluloid truffles to chuck on the barbie.

“We’re all gods in our own world.” The Boys (1998)

The 1986 murder of New South Wales nurse Anita Cobby encapsulated any woman’s greatest fear. Five lowlifes grabbed her on the street and spent all night degrading her battered body before nearly decapitating her, leading to the gang being jailed without the chance of release.

Just over a decade later debut director Rowan Woods decided to loosely base a film on the events leading up to the abduction. Now I don’t normally care for flicks that play with structure, but The Boys’ zigzagging works well, as does its no-nonsense, 80-minute runtime, a combination that leads to one of the most haunting last lines in cinema.

Straightaway we’re thrown into a world in which women are very much third class citizens. None are taken seriously whether they are a protective (but scared) mother or a pregnant girlfriend. They’re ignored, cursed, patronized or seen as a burden, a fundamentally negative attitude that must surely stem from a pronounced failure of upbringing and environment rather than a few porno pics tacked to the back of a door. Indeed, The Boys is an extraordinarily unsettling study of misogyny which shows the only choice women have when around such men as the Sprague brothers is to flee.

We begin with Brett Sprague (David Wenham) being released from a year-long stretch. He doesn’t have one redeeming quality and the goateed Wenham catches the sullen, sneering mannerisms of this permanently suspicious scumbag with aplomb. I dunno what he does with his eyes but his flat, contemptuous gaze is one of The Boys’ more memorable aspects.

Bit by bit we meet his submissive, equally hopeless brothers Glenn and Stevie (John Polson and Anthony Hayes), as well as his spunky, sarcastic girlfriend Michelle (Toni Collette). At a family get-together to celebrate his release, it’s clear he’s returned to a mildly hellish, profanity-filled world of alcohol abuse, long-standing feuds, racism, simmering arguments, antagonistic cops and money worries. At least Glenn’s girlfriend has Brett’s number, though. “You’re a pig,” she tells him. “We all felt a helluva lot safer when you were locked up in jail.”

Although Brett is a violent man, he’s all talk when it comes to women. Sex is clearly a big problem, typified by his inability to respond to Michelle. “How about playing out some of those sexy dreams you told me you had?” she teases, only to be met with surly indifference. His later attempt to have sex with her is a convincing depiction of impotency, inadequacy and rage.

Marvelously written, performed and edited, the little-known Boys is among Oz’s best.

“I’m just a normal bloke who likes a bit of torture.” Chopper (2000)

If you want to see a portrait of a man on a different plane of existence, you’ll do no worse than Andrew Dominik’s sparkling, slightly surreal directorial debut. It centers on the real-life Mark ‘Chopper’ Read, an incorrigible, unapologetic criminal whose aggressive exploits are part hard fact and a shitload of myth. His first jail-bound act of violence captures his capricious, otherworldly nature to a tee. Here he’s locked into a longstanding feud with Keithy George (David Field), a rival for the control of Pentridge Prison’s H Division. In the moments beforehand it’s easy to see that Chopper is a confident, charismatic son of a bitch with a pronounced sense of humor. He’s a bullshitter, a piss-taker and a wind-up merchant.

“You’re sick, Read,” Keithy tells him. “You’re insane.”

“Beethoven had his critics, too,” he glibly replies, as if chatting down the pub. “See if you can name three of ’em.”

Not long afterward he’s stabbing Keithy in the face and neck in front of the rest of the inmates (leaving him lying on the floor in an ever-expanding pool of blood), but it’s his reactions that mark Chopper apart. He simply doesn’t fit the stereotype of a prison hard man. For a start he seems disappointed with himself, if not on the verge of tears, like deep down he knows that violence is self-defeating. He’s concerned about Keithy, offers a cigarette, and reassures him that he won’t bleed to death. However, once Keithy spits back an insult, he mocks his victim as he’s dragged out by the screws leaving a trail of blood. “You all right, Keithy?” he says, offering a little wave. “Off you go. Off to the sick bay. Oh whinge, whinge, fucking whinge.”

Relentlessly glib in the resultant police investigation, things start to spiral out of control when told Keithy hasn’t survived. A contract is put on him and he needs to get out of Dodge, only for one of his own crew to stab him. Again, the man’s sheer unpredictability is underlined by this act of treachery. Not only does he seem unbothered about being repeatedly shanked, but he’s disappointed in his mate. “What’s got into you?” he inquires before being stabbed again in the gut.

Then he hugs him.

Honestly, this is not a normal dude.

Unsurprisingly, Chopper’s near-supernatural tolerance of pain and larger-than-life personality turn him into a media magnet, whether in prison or not. As played by the superb Eric Bana, Chopper is a modern-day folk hero that taps straight into Australia’s long held fondness for outlaws like Ned Kelly. However, the man’s obvious intelligence and disarming wit (he went on to pen a series of bestselling books) can’t manage to obscure a hideously wasted life.

“So you wanna play with the big boys, do ya, little brother?” Two Hands (1999)

The last time I saw the criminal class so woefully dressed was the dungaree and straw hat-adorned rural villains in 1972’s groovy Prime Cut. In Gregor Jordan’s directorial debut they prefer shorts, flip-flops, T-shirts, earrings, mullets, handlebar tashes and bad tattoos while slurping from beer bottles and spouting Aussie slang (“This is gonna be a fuckin’ ripper!”) They might look and sound ridiculous, but they’re still the sort of people that won’t hesitate to wave a shotgun in your face or tie you to a car engine block and drop you in the ocean.

Heath Ledger is our main man, Jimmy. He’s a strip club bouncer in Kings Cross, a nice, colossally stupid guy but a bit of a rarity in that he’s not out to fuck anyone over. However, he is pretty handy with his fists. Pando (an excellent Bryan Brown), the Cross’ big shot gangster, takes notice and gives him a simple errand involving the delivery of ten grand. Jimmy makes a hash of it and suddenly he’s in shit up to his neck…

Apart from the amusing array of sartorial missteps, Two Hands is also unusual in the way it incorporates a supernatural element. Jimmy’s dead older brother, murdered by Pando and his cronies, is not only on hand to offer some narration but take part in events. It’s a bold, not entirely successful move, but it does mark this nicely written, fast-moving comedy-drama out as something different. The cast also features plenty of authentic faces that seamlessly blend into an engaging snapshot of inner-city Sydney.

“Australia… What fresh hell is this?” The Proposition (2005)

With its echoes of Apocalypse Now, this kangaroo western is a sadistic, grimy masterpiece. Set in the 1880s, it focuses on the none-too-law-abiding Burns brothers, two of whom are captured by police in the immersive opening shootout. Charlie (Guy Pearce) is very protective of his simpleton younger sibling, a fact exploited by Captain Morris Stanley (Ray Winstone). This Pommie cop orders Charlie to hunt down and kill his Kurtz-like, older brother Arthur (Danny Huston), a murderous bushranger still at large who’s both a ‘monster’ and an ‘abomination’.

And if Charlie doesn’t comply? Then in nine days’ time little bruvver will hang on Christmas Day.

Charlie sets off on this torturous journey to his much-feared brother’s forbidding hideout, a ‘godforsaken place’ that even the blacks avoid. Meanwhile, we are fed information about the psychopathic Arthur (with the Aborigines believing he has turned into a fierce dog-man living in a cave) as bounty hunters fail to get their grasping hands on him.

Penned by that dark-hearted troubadour Nick Cave, the characters are drawn with great care. This is one of the essential Winstone flicks (the others being Scum, Nil By Mouth and Sexy Beast) and here he plays a man determined to ‘civilize this land.’ However, although he doesn’t hesitate when it comes to striking a man with a pistol butt, he’s still seen as weak by his incompetent, duplicitous subordinates. Matters aren’t helped in the way he tries to domestically recreate a piece of England, having brought a delicate Christian wife that his men want to fuck as she clutches a china teapot or potters around under a parasol in her silly little desert-surrounded garden. Nothing can disguise the fact, though, that Stanley is an outsider out of his depth.

The grizzled Pearce, a million miles from his soap opera days, also excels as the bone-tired middle brother. Faced with an impossible choice, he staggers through the flick not in control of the fierce events but determined to hang onto some sort of morality. His unrepentant brother Arthur, however, is one of the 21st century’s nastier villains, a mini-cyclone of the most appalling contempt for his fellow human beings. Even the lesser characters, like the weaselly upper class twit Eden Fletcher (David Wenham), who is in charge of everything, drip with conviction. Then there’s a terrific cameo from the always welcome John Hurt as a bounty hunter. “We are white men, sir, not beasts,” he tells Charlie with supreme assurance, but the menacing proceedings show such an observation to be anything but true.

The Proposition is filled with authentic, often wince-inducing details, the blackest of humor and starkly beautiful cinematography. Not since Wake in Fright has the outback’s harshness been caught so well. This is a land of blinding sun; swirling clouds of dust; rusty tin shacks; hairy, sweaty, bestial, drunken men; racism; degradation; speared bodies; clinking chains; tormenting flies and rampant brutality. Fright offered the graphic nocturnal slaughter of kangaroos to underline its horrifying lack of decency in a borderline alien world, but Proposition prefers to give us a lengthy, blood-soaked whipping. Indeed, masculine violence imbues just about every frame, making John Hillcoat’s Peckinpah-like directorial kick in the face the perfect flick for misanthropists and man-hating feminists everywhere.

Leave a Reply