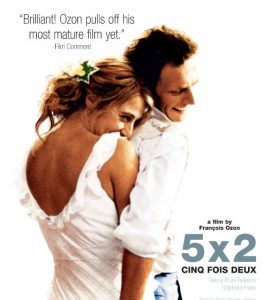

Within five minutes of meeting Gilles (Stephane Freiss), we have watched him sit impassively through divorce proceedings, check into a hotel with his ex-wife, and ass-rape the same woman, all with the stoicism of a philosopher. He is aloof, callous, and greedy, yet pathetic and needy, as he pleads to “try it again” as his now ex-wife angrily walks out of the room. And so begins — or ends — Francois Ozon’s 5×2, a decidedly unromantic tale chronicling the end of love and working backwards to how and why it all went awry. In the end, we are left with little more than, well, “they shouldn’t have gotten married to begin with,” but as presented, we can deduct from Ozon’s method that most people simply don’t belong together, and the adventure of love is at best a fool’s game.

As the title states, this is a film in five parts involving a pair of strangers who become lovers, only to end up strangers once again. It is a careful consideration of the madness of modern amour, with an undercurrent of complete incomprehensibility. Why do two people start dating, continue on that path for a time, get married, have kids, and then, after so much sacrifice and compromise, decide that they can no longer remain a couple? Thankfully, Ozon does not present standard “highlights” to provide obvious clues, such as a bloody beating administered after too much wine, or the discovery of a lipstick-stained collar after the husband sneaks in late from work. Those things are best left to melodrama. Instead, we must pay close attention and largely guess as to the source of both the separation and the attraction.

For a change, the film would have worked just as well if told in a linear fashion, but it’s just as appealing as a retrospective. We can see the resignation on their faces as we open with their divorce, and the humiliation in the hotel that follows instructs us as to the state of Gilles’ mind. He is selfish to be sure (what other kind of man would rape an ex-wife — unless of course she had it coming), but Marion (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi) is no less complicit in that she too agrees to the post-marital assignation. Only she immediately regrets the decision (protesting with only partial vehemence), and certainly did not expect a violation of her poop-chute.

But Gilles insists on such a move, largely because he has no one else (a relationship with another woman is, by his own admission, going nowhere) and the ex- is looking somewhat fetching. We learn about Marion’s mental state as she undresses in the bathroom and returns to the bed wrapped in a towel. He, being a man, immediately suspects that she’s put on weight (and is therefore embarrassed), and remains clueless about her possible fear regarding sex with a man she now despises via state-sponsored decree. This opening round is graphic, twisted, and utterly real, and it sets an engaging tone for what is to follow. After all, we ask, if this man is so disgusted by this point that he has to pound an unwilling ass, what on earth caused the disintegration?

The second interlude involves a dinner party with Gilles and Marion hosting his gay brother and his lover. There’s some drinking and dancing, but the drama peaks when Gilles discusses his presence at a wife-swapping event a year earlier that seems to have been endorsed by Marion. While she waited in the wings, Gilles devoured willing females, as well as partaking a bit of cocksucking on the side. To his brother’s amazement, Gilles even took it in the rear, a revelation that seems to excite the young boy toy most of all. Marion is obviously pained by this dry recitation of the facts, but as she failed to stop it at the time, she seems resigned to what it might say about their marriage.

And what does it say? If I’m being honest, it merely says that these are very open-minded folks who have found a way to live without the Puritanical rules that govern our love lives, but as I doubt Ozon is going that far, I would instead state that at the very least, this is a man who cannot function without openly and unapologetically humiliating his wife. It’s what he lives for. His rage towards her is so complete and all-consuming that he must watch her face as pain registers unadulterated horror. So why does he loathe her with such force?

The third sequence provides few overt clues, although we again witness Gilles at his beastly worst. Gilles receives a call from his wife, who must immediately give birth as the placenta has blocked the birth canal, risking severe bleeding. And yet, despite being told that the situation is very dire, he ignores the request and instead has a quiet dinner alone. He fails to respond to their greatest crisis as a couple. He finally shows up at the hospital, claiming to have been delayed by traffic. But there sit Marion’s parents, who themselves remain married for no conceivable reason as they bicker and trade insults like teenagers.

To make matters worse, Gilles takes off once again, as he can’t stand the sight of his wife in bed and his premature son hooked up in the NICU. But can we really blame him? He’s irresponsible, cruel, and devoid of true empathy, but this is the birth of a child after all, the one event that is most likely to send the male species running for the hills and into the nearest strip club. And how does this clash with the earlier (later) scene where Gilles comforts his son with great tenderness after hearing his cries in the night? Does this mean that the temptation to flee twists and contorts until it becomes resignation? Or has he really changed? Rather than representing the typical cold feet of manhood, I believe this is one striking example of why this marriage could not last. A man for himself alone is not cut out for marriage. And when two selfish twits pair up? Now you have an explanation for the high rate of contract killings among married folks.

Next, the scene shifts to the wedding, which appears to be a happy affair, which shouldn’t surprise anyone who has either been a participant or guest at one of these fascist rallies. The wedding is the human animal’s grandest illusion; painfully choreographed, obsessively planned orgies of excess and deception that set a tone that cannot possibly be sustained. Such laughing, such singing, such unbridled gaiety! It’s almost as if the ridiculous level of pomp is a tacit understanding between everyone involved that yes, we might as well do this now, as it’s all downhill from here.

This can only be the result of having an expensive, showy wedding and reception, as nothing about the life of a marriage necessitates such public demonstrations. After all, these guests will be long gone once the problems begin, and where will such unity be when the couple is forced into the privacy of a cold bedroom? A marriage is between two people alone, and perhaps this is why I respond so viscerally to extroverted beginnings. In any event, Marion and Gilles begin in this manner with little apparent remorse, although the evening to follow holds a few surprises.

Drunk, Gilles passes out in the hotel room, so Marion heads into the night for a little reflection. Sitting on a bench overlooking a tranquil lake, she is approached by an American staying at the hotel. He is almost offensively handsome, and rather unrealistically, he makes a move on her (Marion can speak English, sounding extremely sexy in a way only French women speaking the King’s English can master). He gets rough, and she appears to run from the scene. Or does she? Upon returning to the hotel, it is early morning, which forces us to conclude that Marion gave it up not to her new sweetheart, but some pushy Yank who happened to give even the men in the hotel hard-ons. What does this affair have to say about Marion?

With so much detail left out (we get no real day-to-day interaction between these two), we are left in the dark, which demonstrates respect on Ozon’s part, but also leaves us wanting. Therefore, it’s fair to say that we know so little about these people that we couldn’t possibly care. In contrast, a masterpiece like Scenes from a Marriage gave us so much that it became painfully intimate. Or perhaps the episode is simply one way of showing that these people knew absolutely nothing about each other before jumping in; an all-too-common occurrence for many couples it would seem. When she returns, she clings to her husband with the desperation of a newborn kitten, and we imagine that a lifetime of guilt and suspicion awaits. And so it does.

The final episode concerns their first real encounter, as Gilles meets Marion while on holiday with his girlfriend. He was acquainted with Marion from work, but hadn’t even spoken to her for more than a passing moment. We can tell that Marion is instantly attracted to Gilles, due in no small part to his unavailability. It is true what they say — having a ring on the finger elicits more come-hither glances and flirtations from the opposite sex (it’s safe and it demonstrates that at least one person on this earth finds you desirable), although I’m only citing the literature, as I’ve all but stamped “I’m married” on my forehead and haven’t gotten so much as a partial, gas-induced grin. Continuing, Gilles’ girlfriend is an overly critical bitch (which is obviously weighing on Gilles), but as she’s hot as a firecracker, I would be inclined to ignore such witchy ways, up to and including attempted murder.

Gilles senses something less intense in Marion, and clearly her unassuming ways provide a striking contrast to the current ball-breaker. They go their separate ways at the resort, but run into each other enough that a hint of romance seems just around the corner. But we never see such things transpire. The film ends at the beginning, with Gilles and Marion swimming out to sea, the whole world open to them so long as they ignore their impulses and stay far, far away from each other. It’s easy for Gilles because Marion is “someone else” and for Marion, Gilles is “someone” period, but as a motivating factor for love, things couldn’t be less romantic had an intermediary come in with a carefully prepared contract.

5×2 asks more questions than it answers, and it is far from the definitive statement on love and marriage. That great promise inevitably leads to disaster and sadness is pretty much the theme of life itself, and certainly for the events of this movie. By working from the finish to the start, we are denied the falsity of hope from the opening moment, which is the only realistic way to present human couplings. Even when they kiss, or exchange that look that only lovers seems to understand, it is undermined by the gloom of the concluding act. “Love fades,” the bitter old woman told Alvy Singer in Annie Hall, and while depressing, we damn the doubters and push on.

Some people prefer cinematic expressions of beginnings, as if that undeniable buzz of love’s first sting would course through our veins for eternity. But I am all about the endings. Let me pick over the wreckage like a fevered vulture, after which I’ll gleefully communicate the post-mortem.