2007 Denver International Film Festival

Whenever we envision cinematic tales of authoritarianism and the concurrent loss of liberty, the images rarely go beyond the standard jackbooted thugs, bleak prison landscapes, and dramatic midnight raids; the sort that usually involve fists pounding on doors and the cowering innocents who shake with fear on the other side. Whether the agents of repression are Nazi, Soviet, or standard issue military personnel, the lines of good and evil are clearly drawn, and the stakes so obvious as to be insulting to the intelligence. Freedom has been lost, the good guys want it back, and such heroes spend the entire movie sending cryptic messages by train and telegraph, or having a double agent accept a mysterious package in the night, turn up his collar, and head into the great unknown. Men with guns roam the streets, cameras track and expose every transgression, and ordinary citizens are so battered down by despair that they walk grimly from place to place, pausing only to keep an eye on the shadows.

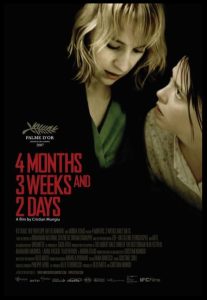

Imagine, then, a movie like 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days; a story of and about Romania circa 1987, when Soviet dominance was in its death throes, but the Ceausescu regime, itself but two years from removal, still exerted its heavy hand on the populace. The film concerns Gabriela (Laura Vasiliu), a young woman who seeks an illegal abortion, and her roommate Otilia (Anamaria Marinca), who has helped arrange the procedure and secure the necessary funds, but at no time is this a polemic, or even the irritating exchange of oft-repeated talking points about sides and positions. While it is political in the sense that we are witnessing an act of rebellion in a country that has outlawed such expressions, the proceedings are so restrained that we focus not on the expected moral questions, but the simple details of what we in the United States take for granted. No one really talks at all about what is being done, in fact, because this isn’t about scoring points or holding placards. It’s a matter of survival, nothing more.

The opening scenes are quiet, low-key, and focused, and though we know what is taking place, there is much to infer, as no one speaks in the sort of platitudes we are used to hearing in movies concerning controversial issues. Plans are made, last-minute pieces of information conveyed, and minor points are reiterated for clarification. Despite the dangers involved (not only defying the law, but the health risks associated with a Back alley abortion), these characters are concerned only with doing what is necessary to get in, get out, and move on. No one has to rail against the government, or stand atop soap boxes preaching to the converted; this is life as it is lived in such a place, and the arguments we find so necessary in the West were exhausted long ago without our involvement.

As we learn the details ourselves in the scenes ahead, it becomes apparent that never before have the evils of totalitarianism been portrayed in this manner. Romania, despite appearing a bit bleak and dilapidated (though no more so than many stretches of big city America), is just like any other place: people take the bus, laugh, eat dinner, have sex, play games, listen to music, and go about their days. It seems obvious in the telling, but as we’ve been trained by the movies to see only opponents shot down in the streets, it may strike us as odd that the powers that be in such countries don’t spend every waking hour bloodying heads and loading dissidents into cattle cars.

And then it hits: oppression works best not when it jails, or kills, or continually threatens, but rather when, through thousands of casual reminders, it forces people to unconsciously adapt to their fates. By altering a thought here, or slightly evolving one’s behavior there, citizens learn to accept the daily humiliations that stem from a loss of individual worth. They may never fully internalize the propaganda (most seem to know when they’re being lied to in such regimes), but by small, almost imperceptible degrees, they become just tolerant enough of their world to help keep order, or at least stay out of trouble. Unlike the visions of 1984 or Brave New World, these societies need far less surveillance than one would imagine. Go too far in a particular direction and such dogs will be loosed upon you, of course, but it’s best if no one ever feels the bite. Self-correction, then, becomes the most effective means of social control. In a few scenes, this is powerfully established with near flawless subtlety, as glances and whispers imply what shouts and speeches would make obvious. Everyone knows the score, but through habit and generations of unspoken instruction, they go through the motions of pretending otherwise.

The abortion takes place in a hotel room, and while it is not the filthy disaster, we’d expect in such a climate of fear, it is so clinical and detached that dehumanization is inevitable. The “doctor”, as such, by Vlad Ivanov with business-like efficiency, and while he is creepy and vile for what he requires as supplemental payment, he is reasonable in one key respect: if they are caught, he would receive the harshest sentence, and as such has the most to lose. More to the point, in any context where people are forced by law or custom to retreat to the shadows, exploitation must always result, providing the best, most lasting argument for abortions legality. Again, this is never spelled out for us directly, but it shouldn’t have to be. And as obvious as it is that no one should be made to feel like a criminal for making such a choice, it’s more important that no civilization be allowed to pay lip service to the value of life while simultaneously devaluing the individual at every turn. In fact, this just might be communisms’ most lasting hypocrisy. Through official decree, all fetuses were required to be brought to term for no other purpose than to grind them beneath the boot heel of a doctrine that held the state alone as sacrosanct. Abortion, then, became the most revolutionary of acts. Through its acquisition, a woman was stating unequivocally that it was far better to risk arrest and death than bring a child into the cold, sterile world of the Eastern Bloc.

Thankfully, the film also refuses to duck the imagery of the procedure, even showing the discarded fetus on the bathroom floor (Otilia also embarks on a disturbing journey to dispose of the remains, which one can’t help but read metaphorically). Many in the audience seemed to have a problem with this decision, but I do wonder how anyone can claim the pro-choice mantle if they are unwilling to face the consequences of that choice. Like it or not, abortion ends a life, and rather than quibble over viability, trimesters, and potential, let’s agree that it involves killing and still hold to its protection. I would never call it murder, of course, for that is a legal definition that carries strict penalties, but to grant the opposition the obvious — a life once started suddenly comes to an end — is to steal away their primary objection and move beyond it altogether. The debate then becomes a matter of priorities: does the decision to terminate always trump the life of a fetus? Does a woman hold full control over her body’s contents, up to the point where they are granted legal status as an independent individual? This conversation does not occur in places like Communist Romania, at least not openly. Even the two women can’t seem to discuss any part of it by films end. That it is under attack in our own country is an obvious source of concern. But so long as it does occur — with all voices strong and passionate throughout — we know at least that one component of a free society remains.

Still, these debates are brought to the film, and will change accordingly as personal preference dictates. In their place stands a film of crushing realism; a masterpiece of social commentary that steadfastly refuses to pitch to the cheap seats. We see no bogey men whatsoever, and no walls blocking out the sun, only the dying embers of an idea that dared suggest that man is best when caged and subdued. We sense the turning tide, best seen in a generational dispute at the dinner table (though two key characters remain all but silent), and know that while some long ago gave up the fight, there are new voices in the wilderness that have had enough, even if they aren’t’ fully aware of it themselves. It’s a film about freedom and its absence, yes, but just as powerfully it takes the unaware on a journey through the black markets we don’t want to believe exist; not just for drugs, rare goods, or forbidden delights, but the human will itself. Though underground, it can’t long remain dormant.