Dramas: The Chase (1966), Network (1976), The Betsy (1978), The Great Santini (1979), Tender Mercies (1983), The Natural (1984), Rambling Rose (1991), The Paper (1994) & The Scarlet Letter (1995)

The Chase united Duvall with Brando for the first time, but although it’s the lesser known of their collaborations this one is worth hunting down. Duvall plays the disappointed, buttoned-down vice president of a bank in a small Texas town. With his neatly combed hair, glasses and aversion to fun, he’s a worrywart that gets ‘upset by anything and everything.’ Perhaps this is fair enough, given he’s being cuckolded by his fellow VP and emasculated by his lively, contemptuous wife (“He don’t have no pistol.”) Meanwhile, a similarly cuckolded convict has busted out of prison and is heading back to his old stomping ground, ensuring one hell of a Saturday night for the townsfolk…

The Chase is a bleak, often queasy depiction of rich bastards behaving badly, mixing oil, race, drunkenness, adultery, simmering secrets, violence, vigilantism and family dysfunction. There’s something corrupt, facile and hopeless about most of the people on show. They’re rubberneckers at best and actively malicious at worst, populating a town with a rotten heart. With a terrific cast that includes Jane Fonda, Robert Redford, Angie Dickinson and James Fox, The Chase is intelligently written with an unusual junkyard finale. Duvall is solid, but he’s no match for an on-fire Brando (in the middle of his sixties wilderness) as the town’s sickened sheriff.

Duvall inhabits another sick world in the extraordinary, multi-Oscar-winning triumph Network. Here, however, he’s an active part of the greed, happy to exploit a man’s failing mental health if that means his struggling television network UBS and its loss-making news division can get back on top. Indeed, morality and so-called ethical behavior mean nothing when up against the juggernaut of ratings. Money trumps everything – dignity, fair play, compassion, empathy, the whole shebang.

Duvall is heavyweight boss Frank Hackett, his surname giving a fair idea that subtlety is not a part of his game. He’s a ‘corporation man, body and soul’. At first, he dismisses a long-time news anchorman’s on-air promise to commit suicide as a ‘grotesque incident’ and demands the guy is never put in front of a camera again. However, once the ratings come in, he’s talked into giving the ‘manifestly irresponsible’ anchorman another chance (although he covers his arse by talking to the lawyers first). He even justifies the controversial move by telling fellow executives that he’s merely adding ‘editorial comment’ to the evening news show. The anchorman quickly strikes a nationwide chord by turning into a ‘mad prophet’ railing against all forms of bullshit. Suddenly the ailing network has a gargantuan hit on its hands and the ruthless, cost-obsessed Hackett looks like a hero in front of the top brass and stockholders.

Like everyone else in the prescient Network, the ‘hatchet man’ Duvall is superb, perhaps at his best when locking horns with the lone voice of morality, William Holden. Just look at his glee as he fires his long-time nemesis while thrusting his hips and crowing, he’s got a ‘big, fat, big-titted hit’. And when it all goes to shit? He doesn’t hesitate to act, calmly demonstrating a belief that human beings are little more than commodities. One of Duvall’s key roles it’s a seething, self-centered and mean-spirited turn.

The overlong, action-free The Betsy does its best to tell you it’s about cars, racing and the automobile industry but really, it’s about fucking. Like British rubbish released around the same time (The Bitch and The Stud), this one focuses on the soft-core fumbling of the upper class. Of course, the one question that needs asking is: What’s Laurence Olivier, often hailed as The Greatest Actor of the Twentieth Century, doing in this trash? I mean, here we get to see him bang a young chambermaid, drunkenly caress a car, talk about ‘jerking off’, threaten to break a young Tommy Lee Jones in half, and enjoy relations with his love-struck daughter-in-law (Katharine Ross, a heartbeat away from walking into an even bigger disaster, The Swarm). It’s toe-curling stuff all the way, but disappointingly never becomes sleazy. In fact, it’s like an ultra-dull, car-filled episode of Dynasty.

Duvall plays Olivier’s resentful grandson, the president of the old man’s automobile company. He’s against plans to develop a new family car and is also in a bit of a longstanding strop about his mum having been diddled by Lord Larry. “Look at him,” he says of Olivier at one point. “Sonuvabitch thinks he’s cock of the walk.” Well, on this overripe evidence, he’s definitely the cock of something. Duvall might be cheating on his wife (and in turn having his new squeeze prodded by Jones), but he keeps his clothes on and puts in a more dignified shift than the others, even if as a young kid he bounced from witnessing his father’s suicide to his mum cuddling granddaddy in bed within thirty seconds. That’s gotta put you off your homework. Special mention must also go to the gorgeous Kathleen Beller (the Betsy of the title) who tries hard, but doesn’t manage to act past her voluptuous breasts in a single scene.

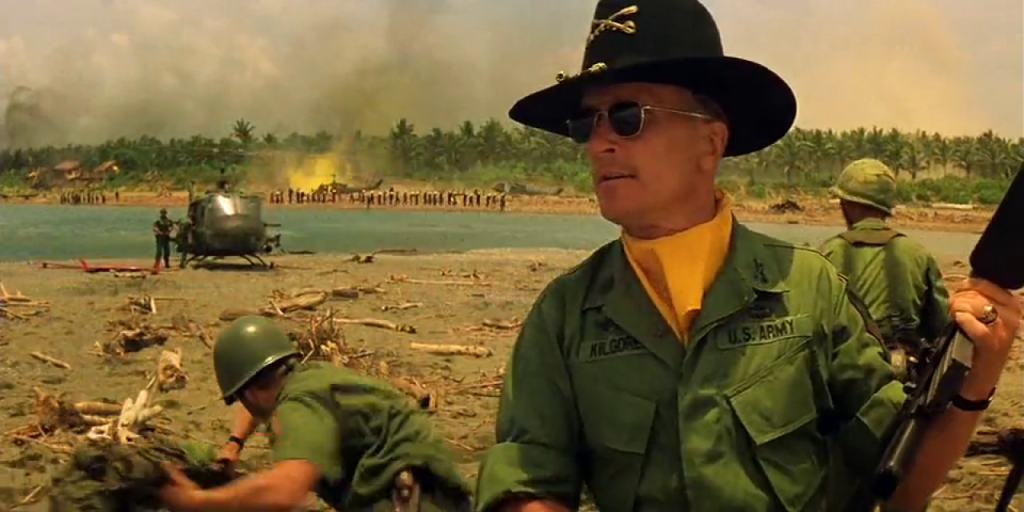

Duvall played two military gentlemen in 1979, the better-known one striding around war-torn Nam, spitting out racial insults and plotting slaughter in Apocalypse Now. Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore is not all bad, though, as he’s also keen to introduce a little culture into the lives of the natives via a certain German composer. Kilgore is the personification of both grace under pressure and psychopathic arrogance, unbothered by nearby explosions and so convinced of his battlefield invincibility that he prefers a hat to a helmet. If you want to argue Duvall makes an indelible contribution to one of the greatest war films of all time, immeasurably aided by those quotes about Charlie’s disdain for surfing and the olfactory pleasures of jellified fuel, I might have to agree.

Duvall snagged a much bigger military-flavored role in the box-office dud The Great Santini. He’s mainly terrific as ‘the greatest Marine fighter pilot that ever crapped between two shoes’ but boy, he’s let down by two supporting performances. He plays the iron-fisted titular character, a mustachioed colonel so in love with the army that he strides around in uniform even when off duty. Like Kilgore, he spends a lot of time with his hands on hips, convinced he’s untouchable and always knows best. He’s the sort of unbearable ass that starts a new posting by ambushing a defecating corporal and shoving his head down the bog. “Do you realize several Marines were killed at Pearl Harbor while taking craps?” he bellows in the guy’s dripping face. “A fighting man must be vigilant to surprise attack no matter where he is. The survival of our nation depends on the readiness of Marines all over the world.” I think this means no Marine should ever take a dump while on duty. Later, when formally meeting his junior officers, he tells them: “If I say something, you pretend it’s coming from the burning bush.”

This self-important rigidity extends to his family, the members of which he’s dragged from army base to army base while routinely treating as subordinates. And woe betide any of them if they disobey a direct order. Not that he doesn’t love and want the best for them. It’s just he goes about things in the wrong way, such as giving out birthday presents at 4am. “Would you like to be killed in action, dad?” his eldest son Ben (a dreadful Michael O’Keefe) asks. Duvall shrugs. “It’s better than dying of piles,” he replies.

Sometimes, though, his desire to instill discipline slips into outright bullying, best illustrated by a classic basketball scene during which Ben beats him for the first time. Duvall, unable to accept the result, spends the next two minutes following his son through the house and up the stairs bouncing the ball off the back of his head while demanding: “Do you wanna cry?” Later Duvall is seen playing alone in the middle of the night during a rainstorm, obviously punishing himself and determined to never be beaten again.

With its Top Gun-like start that surprisingly shows you don’t have to be a buffed, latent homosexual to fly jet fighters, the 1962-set Santini has a smooth, gently amusing first hour. However, it starts dropping the ball by introducing a simplistic bout of racism. Ben makes friends with a bullied black stutterer only for things to quickly go pear-shaped, the entire episode not only blighted by unintentionally funny acting but then hastily dropped. Oh well, this might be a lesser movie with a rubbish final half-hour but Duvall’s abusive, rod-up-his-ass performance is still worth a watch.

And now for the big one. Or at least the one that snared Duvall the top trinket. Tender Mercies is such a small, gentle film that it barely fills the screen. Duvall is a formerly famous country and western singer down on his luck. His career’s over, he’s drinking too much, he has a successful ex-wife that hates him, and hasn’t seen his teenage daughter in seven or eight years (“I never trusted happiness. I never did. I never will.”) Things start to pick up when he gets in with a young widow and her mercifully unannoying son at a roadside motel. Will he seize such an unexpected opportunity or start waking up again with a vomit-smeared pate?

Duvall puts in a fine, low-key performance, but it pales next to the likes of Tom Hagen and Kilgore. Most of the time he’s dressed in denim with a straggly beard staring into the middle distance. Occasionally he sings and strums a guitar. Not exactly rip-roaring stuff, you know? Sometimes I have little problem with the Academy recognizing powerhouse performances like Raging Bull’s De Niro or Wall Street’s Douglas, but Duvall’s honoring feels more like an accumulation of brownie points (see Scorsese, The Departed). In 1983 Duvall beat off Educating Rita’s Michael Caine but I feel the latter’s turn is fifty times more memorable. Tender offers barely a raised voice throughout and what I can only assume is a deliberate dearth of memorable lines and scenes. It’s authentically minimalist and I wasn’t bored, but it’s not the reason I watch movies. Tender is very easy to forget and merely adds weight to my growing belief that playwrights should be discouraged from penning screenplays.

Duvall’s Oscar win did not open the floodgates when it came to juicy starring roles. Hell, perhaps he was never interested in all that high-profile malarkey, but the rest of the eighties was a distinct disappointment that only coughed up one bonafide hit in the form of Colors. Tender’s immediate follow-up, though, was the sport-flavored The Natural. Now you might disagree, but I find the obsessive Yank love for baseball head-scratching. No one gives a flying fuck about baseball in Britain or Oz. In fact, when I was growing up it was called rounders and played by giggling, lightly perspiring girls. Call me picky, but baseball bats should never be used to hit baseballs. They should instead be employed to batter misbehaving gangsters to death à la Casino or The Untouchables. Hence, you can understand my reluctance to settle down in front of a sincere, two-hour plus baseball flick, especially as I hadn’t long watched that similarly themed, laughably bad Wesley Snipes vehicle, The Fan.

The badly written, stitched together The Natural, starring Robert Redford at his blandest, offers no real plot. It just ambles, sometimes corny, often bloody daft, and always below par right through to its unexciting, preposterous finale. Perhaps it wants to say something about corruption and integrity, I don’t know; I was too distracted by the weird stuff, like the middle-aged Redford playing a teenager at one point and the suggestion that the nearby presence of different women can affect how you swing a bat. There’s also some sort of mystical vibe going on that plain fails. Duvall pops up as a dogged, weasel-like reporter. We get to see him type, draw some pictures, smoke a cigar, suffer several near misses with a speeding baseball and not influence events in any way whatsoever. Robert, my old son, you’re an Oscar winner so why put your hand up for such a non-role? Sure, he takes his place in an interesting cast (that includes a young Michael Madsen undergoing a ridiculous demise, a redundant Glenn Close and a barely recognizable Kim Basinger playing a half-baked femme fatale) but to use an awfully clever baseball metaphor, everyone strikes out in this flat, sugary shit. I suggest you watch The Bad News Bears instead.

Duvall never marketed himself as a stud muffin nor showed any interest in plunging into the sexy stuff, despite his career coinciding with the rise of permissiveness in cinema. Outside of THX 1138 it’s tricky to even find him in a sex scene so to see a sobbing young woman lose her shit over his sexagenarian ass in Rambling Rose and plead for a kiss is a bit of a stretch. He initially caves into the temptation dangled before him by Laura Dern, but a few moments later he’s on his feet, jabbing a finger and telling her: “Put your damn tit back in your dress… Replace that tit!”

The feminist-flavored Rose centers on the arrival of the titular character (Dern) as a domestic servant at a Georgian house during the Great Depression. Given this ‘crazy creature’ tries to seduce the married Duvall and then allows his thirteen-year-old son to implausibly finger her to orgasm, she’s a slut. Of course, in modern parlance we’re supposed to be more sensitive and perhaps refer to her free and open sexuality, but she’s a slut. Dern feels miscast. Like Karen Black she’s got weird, sunken eyes set in a semi-masculine face, and I would have preferred someone sultrier to have taken on the role, such as Drew Barrymore.

Duvall plays a conservative, slightly sexist Southern gentleman, but it’s a passive role in which he doesn’t do much more than reject Rose’s advances, suffer from insomnia, have slight arguments with his dippy wife and trot out the Southern accent he used in Tender Mercies. His most energetic bits come while chasing off suitors lured to his property by Rose’s constantly wafting pussy. Despite its impeccable period detail, Rose isn’t a good watch, hindered by an opening scene in which we’re told she ‘caused one hell of a damnable commotion’. Events tend to show otherwise and herein lies Rose’s problem; it’s a sedate, underwhelming flick that keeps hitting the same note.

In The Paper Duvall plays the heavy smoking editor-in-chief of a cash-strapped New York paper during a frenetic twenty-four hours. He’s got an enlarged prostate, an estranged daughter, and often has to act as an adjudicator between his squabbling subordinates. “The problem with being my age is everybody thinks you’re a father figure,” he tells a wantaway editor looking for advice, “but really you’re just the same asshole you always were.” He starts off pithy and ends up sappy in another of those roles in which he doesn’t contribute anything significant to the storyline. Apart from Splash, director Ron Howard is Not a Fave and wouldn’t be able to come up with anything edgy if his ginger pubes depended on it. This is another predictable, candy floss effort, especially when compared to Network’s dark, fantastic rumination on the evils of broadcasting.

Duvall utilized his well-honed strategy of appearing alongside rising stars by hooking up with Demi Moore for The Scarlet Letter. And why not? Mrs. Bruce Willis was about to become the highest paid actress in the world after the box-office gold of Ghost, A Few Good Men, Indecent Proposal and Disclosure. Unfortunately, 1995’s Letter was the first in a series of disasters that culminated in the following year’s annus horribilis of The Juror and Striptease. Soon afterward the macho nonsense of G.I. ‘Suck my dick!’ Jane delivered a near-knockout blow to her career as a major Hollywood force.

Not that Duvall had any foresight Moore was about to become box-office poison in Letter. He plays her Puritan hubby in 17th century Massachusetts, presumed dead in an Indian massacre. This frees her to get jiggy with the colony’s minister (Gary Oldman) after which she winds up pregnant, imprisoned and scorned. Meanwhile, a narrator tells us that the not-so-dead Duvall has become a naturalized Indian and gone a bit doolally: “Freed from Puritan society, he was with increasing regularity seized by spirits so powerful they were terrifying even to the Indians.” Cue shot of a Duvall doing a hopping dance while wearing a dripping, recently slaughtered small deer on his head. “Forgive me, Lord,” he says post-dance after collapsing flat on his back with a nonplussed squaw crouching over him, although I’m unsure if he wants clemency for his dodgy Indian impersonation or horrendous attempt at an English accent.

Whatever the case, our Bobby has landed smack bang in the middle of one of the worst regarded films of the 90s. Surely an actor of his gravitas could eventually improve matters? Nope. He soon drops his Indian flirtation and nips off to the colony to dementedly try to discover who got his wife (the far too contemporary-looking Demi) up the duff. He’s mannered, occasionally effete and plain daft in every scene. I’d say it’s his worst performance since his gay histrionics in Nightmare in the Sun, but this glossy flick isn’t as bad as its reputation.

A lot of the flack it took centers on the way it differs so much from the novel. Christ, who cares? Movies and books are different entities. It’s not a writer’s or director’s job to faithfully reproduce source material. It’s their job to come up with something entertaining so judge a flick on its own merits rather than how closely it apes a beloved novel, especially as this one offers a disclaimer up front that it’s ‘freely adapted’. Anyhow, I’m glad I watched as I got to see a nutso Duvall do an Indian war cry and scalp a man.

For Duvall Part 4, Click Here

Leave a Reply