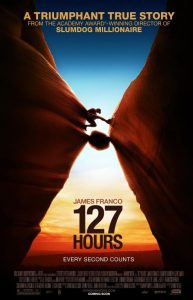

Contrary to what the title would have you believe, this is not, in fact, a radical experiment in film that has a running time of five days. When I found that Danny Boyle’s new opus clocked in at just over 90 minutes, I felt shortchanged. Once the film was underway however, I realized that it would only seem to be a slog lasting so long. I am being a bit unfair, as 127 Hours is not a bad film. In fits and stretches it is effective at conveying the danger that its real-life subject, Aron Ralston, experienced when he was trapped by a boulder in an isolated canyon.

Crafting a movie about a guy stuck in one place would seem to be a difficult project fraught with the risk of inducing a static boredom in its audience. In response, Boyle filled the running time with a riot of technique and flash that keeps the affair humming with energy. And just to be on the safe side, the audience is given constant prompting about a greater lesson lying herein via endless flashbacks and imaginings with all the subtlety of a gamma ray burst. James Franco gives a complete performance as Ralston, but is left well in the shadow of the highly distracted director, whom I was hoping would be left pinned to a boulder as well until he calms down a bit prior to his next endeavor.

You know the story, and you know the ending, so I will not hesitate to spoil this one. Aron is a weekend hiker who revels in an adventure. He spends his time in places far from humanity, skipping about the ledges and cliffs that he has come to know like his own backyard. Familiarity breeds contempt, and so we wait for the rock to drop. In the meantime, Franco paints a portrait of an annoying Mountain Dew commercial (the drink gets some screen time as well) come to life. When the constantly moving camera stops for a moment, it takes in some truly stunning vistas.

Meanwhile, the main character is an aggressively annoying douche who appears to labor immensely to impress himself to the point of filming his exploits. These are places of impossibly ancient beauty, and yet are made to seem a pointless playground. Maybe this is just my prejudice, as everyone has their own way of defining beauty or appreciating nature. I have no indication this guy appreciates anything but himself in action. Whatever keeps you out of trouble, I guess. Or not.

In short order, he traipses over a loose boulder that pins him to a wall deep in a crevasse. One nice shot carries us out from our protagonist into the vast stretch of a near-wild region that swallows whole his pleas for help. It is made clear just how desperate his situation is from the very start. Sleep is a struggle, and his life is threatened by blood loss, the near-freeze of the night desert, his hunger, and most acutely his thirst. Storms become an enemy beyond reckoning, while he gleefully awaits the 15 minutes of sunlight he is allowed each day. His greatest enemy, however is solitude, and the tricks that it can play upon a mind that should be focused on escape. In this sense, Boyle is right for the job in visualizing how the brain can wander off to more pleasant places, like a party with beer and people that can be touched.

He remembers a girl who got away, family that has been neglected, and his precarious connections to the rest of the world. 127 Hours hammers home the point that our species is a gregarious one, and requires some interaction to survive. Solitude is desirable to those who are independent, and relish the quiet and introspective moments (not this guy, of course). There is a trade-off, in that when you are in trouble, you may lack those connections that could save you. This is made clear, and in the event you did not get the point, it is made repeatedly so as to pad the running time to feature length.

This becomes a problem as the money shot approaches – Aron must saw off his arm with a dull tool in a sequence that should rival the final shots of Aguirre floating down the river on his raft in terms of haunting solitude. The film up to this point has been so full of noise and distraction that it is difficult to truly feel that visceral edge. A far better example of this was made in Gerry, a film that shared a location and some themes with 127 Hours. The execution, however, was that of suppression. The location and the silence guided Gus Van Sant into making a truly odd and inspired masterpiece. This movie resembled Into The Wild, both with its annoying lead character and the sledgehammer sensibility that went into ensuring its moral was burned onto everyone’s frontal lobes.

As Aron prepares to do the thing with his thing, he considers his place in the world. “This rock has been waiting for me my entire life.” His egocentric view did not change from the opening frame as he danced in an unforgiving wilderness as though it were his living room. The rock was not waiting for you. It does not give a toss about you, and will likely outlive you in its crevasse. You, as such, do not matter. A small supporting character on a far greater rock that has barely registered your existence. This sentiment is not meant to be nihilistic, but rather realistic.

We do not leave messages with friends or family about where we are going because we care (even though we do), but because we are being careful. Because we do not trust that we are infallible or that anything is under control. There are larger forces at work, and they are not out to destroy us – our passing is incidental. The film is smaller for that reason for lacking a larger perspective. That, and the intrusive hand of the director that made 127 Hours simultaneously brief and interminable, and unnecessarily so.