For over 30 years now, ever since his debut feature She’s Gotta Have It in 1986, Spike Lee has been one of the most innovative and provocative filmmakers of our time. As expressed numerous times throughout his many films, Lee’s highest goal is to “wake up” and uplift all oppressed and deluded people, but he has an understandably primary concern for his own people, the African-Americans who have been abused and misrepresented in the United States ever since before it was even called the United States.

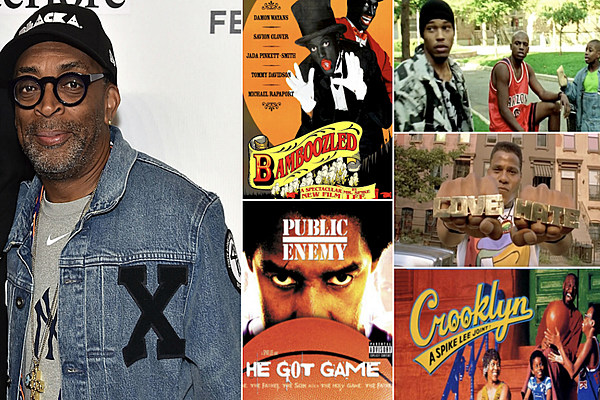

Some critics have accused Lee of the same bigotry his films abhor, citing in particular his three best movies (Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, and Bamboozled) as being counterproductive and causing, rather than alleviating, the tensions between various races, but particularly between blacks and whites. Yet all one has to do is view these films to see Lee’s love of all humanity; each one is an eloquent cry of pain at the inhumanity bred by racism.

Do the Right Thing (1989) is an often funny and always heartfelt look at bigotry and racial tension. After a highly stylized opening sequence bathed in red light to set the tone (which, according to Lee in his book on the making of the movie, is designed to have “people in the theaters sweating as they watch”), the first image is a close-up of Mister Senor Love Daddy (Samuel L. Jackson) saying, “Wake up!” This phrase is common throughout Lee’s films and clearly has a deeper meaning than the literal one attached to Love Daddy’s dialogue.

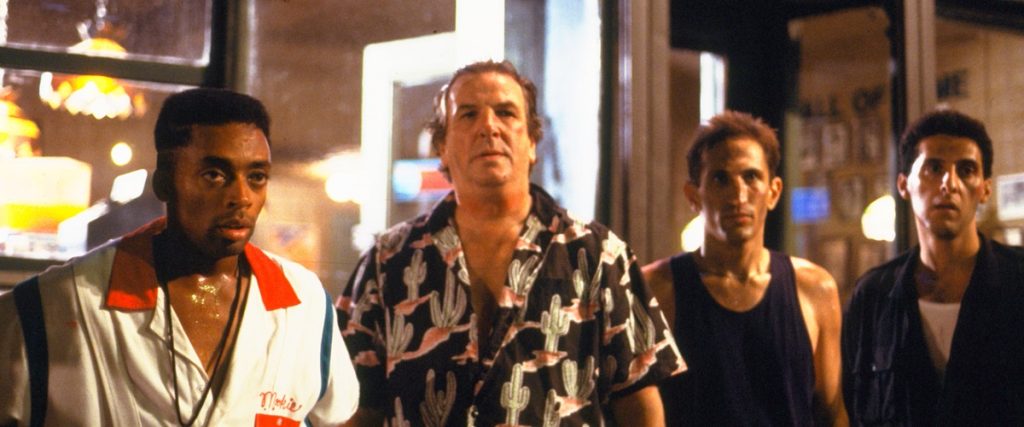

The character of Mookie (Lee) is, in part, a symbol of one of the primary ways to uplift the Black race; as Mookie says, “I got to get paid!” This is his driving motivation, an idea explored over a decade later in Bamboozled (2000), which examines what a person should or should not be willing to do in order to get paid. In Mookie’s case, he is willing to put up with the racism of Pino (John Turturro) in order to stay gainfully employed. Even Sal (Danny Aiello) is, in effect, the benevolent plantation owner. He is kind to Mookie, Da Mayor (Ossie Davis), and his black customers but seems to lust after Jade (Joie Lee) and, ultimately, is not above using racial epithets and even equating the life of a black man (Radio Raheem, played by Bill Nunn) with a piece of property (his business, Sal’s Famous Pizzeria).

On the more revolutionary side of uplifting the race is the gradually developed trinity of protest: Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), Radio Raheem, and Smiley (Roger Guenveur-Smith). Buggin’ Out is seen as something of a joke in the neighborhood, as evidenced by his rather pointless and ineffectual confrontation with the white yuppie Clifton (John Savage), who scuffs his Air Jordans, as well as by the reactions of various neighborhood people to Buggin’s suggestion of boycotting Sal’s. Radio Raheem is the one who actually commands respect in the neighborhood, which is shown particularly in two scenes: the boombox battle between Raheem and the Puerto Ricans, and the Night of the Hunter homage in which Raheem tells Mookie the story of Love and Hate. Ultimately, it is Raheem that actually incites the conflict, as Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” blares from his boombox, driving Sal into a fit of racist madness. The classic “Vertigo shot” (zooming in while simultaneously dollying out) is used in conjunction with extreme low and oblique angle photography to enhance the discord of the scene.

When the fire department comes, they train their hoses on the rioting people first, showing how little has really changed since the civil rights demonstrations of the 1960s. When the crowd turns on the owners of the Korean market, they escape destruction by saying, “Me no white. Me black.” This is inspired by a real-life incident recounted in The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley: during the “long, hot summer of 1964, Korean shop owners escaped the destruction of their business by posting a sign in the window saying, ‘We colored, too.’” As Sweet Dick Willie (Robin Harris) says to Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison), “Your ass got off the boat, too.”

Do the Right Thing has a coda showing the aftermath of the violence; this represents the circle of life. When Da Mayor says, “We’re still standing,” he speaks for oppressed people all over the world, and particularly for African-Americans. This is followed by a pan over to Mookie as he prepares to stand tall before Sal. The two are shot from an extreme low angle, making them pillars of their respective races and viewpoints, not unlike Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten in Citizen Kane. Under the surface, tacitly, Mookie apologizes and Sal forgives him and, in a way, vice versa, a conclusion that was more blatant in the original shooting script, in which Sal reiterates Da Mayor’s advice of “always try to do the right thing.” This deceptively simple bit of dialogue is the heart of the film’s conflict: who is to say what “the right thing” is?

Lee underscores this conflict with the film’s closing quotes, showing Malcolm and Martin’s differing viewpoints on the use of violence in the struggle for respect and human rights. However, the final image in the film is that of the two great leaders smiling and shaking hands, showing that these two viewpoints are not entirely irreconcilable; each individual has a choice of with which they agree. As Lee says in the aforementioned book on Do the Right Thing, co-authored with Lisa Jones, “Yep, we have a choice, Malcolm or King. I know who I’m down with.”

Indeed, Malcolm X (1992) may be the movie Lee was born to make. Ever since he read The Autobiography of Malcolm X for the first time, he had a vision for the film. He says in his book By Any Means Necessary: The Trials and Tribulations of the Making of Malcolm X, co-authored with Ralph Wiley, “it was because of Do the Right Thing that a man named Marvin Worth, who had the rights to the material on Malcolm’s life, sent… a letter saying he wanted me to direct the film.” At that time, the project was being developed by Norman Jewison, a white filmmaker. According to Lee’s book, after some debate, Jewison told Lee, “I don’t know how to do this film, I can’t lick it,” and wished him luck.

The results are incredible, a 70 millimeter epic shot in New York, L.A., Africa, and the Middle East with an excellent cast and a great script based on an earlier version by no less a writer than James Baldwin. Though its scope is much larger, Lee retained the integrity and strength of Do the Right Thing by employing much of the same crew, including cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, costume designer Ruth Carter and production designer Wynn Thomas. In this way, he brings an epic story of great magnitude down to a human level.

The title footage of Rodney King, intercut with the American flag, has the same effect as the fire hoses in Do the Right Thing: it makes the viewer ponder just how far we’ve really come since the days when leaders like Malcolm had to fight for human rights. The opening tracking shot of Shorty (Lee) walking down the street in Boston is also reminiscent of Mookie’s walk down Stuyvesant Street, and since both characters are played by Lee, the implication is of the filmmaker personally taking you on a journey through his work.

Lee’s treatment of interracial relationships is important in all three films. In Do the Right Thing, both Mookie and Pino hate the fact that Sal is attracted to Jade. In Bamboozled, Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport) thinks he has “a right” to say “n****r” because he has a black wife. In Malcolm X, we see Malcolm’s (Denzel Washington) deep-down hatred of his white girlfriend Sophia (Kate Vernon) in the scene in which she feeds him eggs. Malcolm resents the fact that she is with him because he is black; this treatment is similar to his status as a novelty, or mascot, in school, where he “was unique… like a pink poodle,” as quoted in The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Betty Shabazz (Angela Bassett) is one of Lee’s strongest female characters. Though it is a relatively small role, she is an important and prescient force in Malcolm’s life, seeing the Nation of Islam’s betrayal even before Malcolm, who correctly predicted his own death. When Malcolm does realize his own betrayal, the scene is extremely evocative, with its crucifix-like composition of the window frame behind Malcolm as he prays; the backlighting evokes Malcolm as a prophetic figure. When Malcolm visits Elijah Muhammad (Al Freeman, Jr.) after the former’s infamous remarks on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, we see for the first time signs of Muhammad’s bronchial asthmatic condition. It is as if Malcolm’s remarks caused this condition, an implication that underscores the mutual disappointment between the two men.

Throughout the movie, Lee intercuts black & white footage of Washington as Malcolm, as well as actual historical footage, to lend the film a sense of authenticity. Nowhere is this technique better used than in the Mecca sequence, some of which was shot in 16 millimeter, perfectly emulating footage of the real Malcolm X in Egypt, which we see at the end of the film. Lee had to fight tooth and nail with the Completion Bond Company to actually shoot overseas. As he says in By Any Means Necessary, “How can you have 160 minutes of Malcolm saying white people are blue-eyed devils and then not go spend the time and money to shoot the pivotal moments that caused him to turn around on that thinking?” Lee’s vision persevered, and the film is decidedly better for it.

At the Audubon Ballroom, the applause at the beginning of the scene is cross-faded, making it sound vaguely like a siren. This indicates the impending violence of Malcolm’s assassination, which is rendered with just the right amount of intensity: shocking, but tasteful. Bassett’s portrayal of Betty’s grief is absolutely heartbreaking, as is Ossie Davis’s subsequent reading of his eulogy for Malcolm; cut together with footage of the real Malcolm X, this is one of the most moving scenes in film history. One of two quotes that end the movie is Malcolm saying, “You haven’t done the right thing!” in a small self-referential moment that ties the film to Lee’s earlier masterpiece. The other is the final image, after Nelson Mandela and a group of South African schoolchildren illustrate the significance of Malcolm’s life and teachings to today’s world, and Lee cuts to actual footage of Malcolm delivering the final words, “by any means necessary,” a credo which Lee has adopted for his 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks.

Bamboozled, the 15th Spike Lee joint, is his first movie even cut on video (Lee prefers the 35 or 16 mm Steenbeck flatbeds), let alone mostly shot on it. Cinematographer Ellen Kuras used consumer mini-DV cameras to achieve a television-like feel for most of the movie. The TV show itself, Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show, was shot on 16 mm to give it a higher production value than “real life,” while the bulk of the movie was shot on multiple low-end digital video cameras, in part for budgetary reasons. One advantage of shooting with multiple cameras (sometimes as many as fifteen at once) is that every scene can then be shot in one or two takes without destroying spontaneity or hindering the actors’ ability to improvise. As Rapaport says on the DVD, “It’s almost like shooting a play.”

Bamboozled opens with the sounds of ships creaking on ocean waves, together with Stevie Wonder’s song, “Misrepresented People,” which creates a sense of history that is very important in a movie about a modern-day revival of an old racist tradition: the minstrel show. The first spoken words we hear are a dictionary definition of satire, read by Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans), referred to throughout the movie as “Dela.” We later find out that his exaggeratedly precise diction and, in fact, even his name, are fake. He, like other major characters in the movie, are satirical caricatures, or stereotypes. He and Sloan (Jada Pinkett-Smith) represent the so-called “Uncle Toms” in the white corporate power structure. Dunwitty represents the white media’s appropriation of black culture. Big Blak Afrika (Mos Def) and the Mau-Maus represent the uninformed pseudo-revolutionaries of the rap world. Manray (Savion Glover) and Womack (Tommy Davidson) are probably the most realistic characters in the movie (though, as Lee says of Dunwitty, “I’ve met people like this”). When Manray and Womack become Mantan and Sleep n’ Eat, their personalities are abusively exaggerated until they too are caricatures of their former selves.

Lee and editor Sam Pollard delicately use television techniques such as the “MTV” editing style of the inspiration scene, in which we see Dela and Sloan simultaneously thinking of Manray, to evoke the oversaturated, hyperkinetic feel of modern-day media. The over-the-top performances also contribute to this satirical edge, particularly in the pitch scene, in which Dela says, “I’ve never really dug deep into my pain as a Negro,” and Dunwitty characterizes Keenan and Kel as “the stupidest shit on TV, yo!”

This is undoubtedly Lee’s most self-referential film: Dela’s original aim is to destroy old-fashioned racist stereotypes by satirically exploiting them, just as Lee is doing with the movie itself. Much of this self-reference comes in the form of ad-libs, as when Dunwitty says, “I don’t care what that prick Spike Lee says, Tarantino was right,” or when Dela describes a minstrel show as “singing, dancing, telling jokes, doing skits… like In Living Color,” a TV show on which both Wayans and Davidson got their start. These and many more self-referential ad-libs might have been lost if the movie had been shot more conventionally.

The scene in which Manray auditions for Dunwitty is extremely dehumanizing, as was the application of blackface for the real-life actors; the tears on Davidson’s face in the later “Showtime” scene are real. Manray, now officially dubbed “Mantan,” is asked to dance on the boss’s desk, and Dela eagerly gets up, saying, “Here, take my chair,” in perhaps a subtle nod to the famous Rosa Parks incident and the regressive laws it helped to change. Glover’s tap-dancing is incredible, and the fact that he can do this for a living is good enough for his character, while the more intelligent Womack is skeptical from the start, but also seduced by the money.

Lee’s influences (including Sunset Blvd, A Face in the Crowd, and The Producers) are apparent to anyone familiar with them, especially the riff on Network in which Mantan screams, “I’m sick and tired of n****rs, and I’m not gonna take it anymore!” Later, Manray amends this to “I’m sick and tired of being a n****r,” a slap in the painted face of the audience, who represent all of America, especially the media. We symbolically put on blackface, as the audience does literally, by appropriating the most appealing elements of Black culture without due respect and compensation to the people who created it, or acknowledgement of the circumstances our society has created for them. As critic Stanley Crouch says, historically, “the grand irony… is that it’s as though [minstrel performers] came and reinforced the bars of the cage they were in, because of their talent.” Kuras used blue gels when lighting the minstrel performers in order to suggest the bars of this mental and spiritual prison.

Though Lee characterizes the Mau-Maus as “idiots [who] think they’re uplifting the race by taking a life,” he uses Big Blak Afrika’s dialogue to express his feeling that “gangsta rap is a 21st century version of a minstrel show.” Lee also uses Sloan’s dialogue to explain why he himself, like her character, collects old racist memorabilia, “to remind me of a time when we were considered inferior.” Lee kept one of the film’s most important props on his desk while writing Bamboozled, and Dela’s office likewise becomes gradually more cluttered with these artifacts until, as if by osmosis, these images overtake his mind and he finally “grows” blackface.

Bamboozled ends effectively as Malcolm X does, with a montage of real historical footage, but while the shots of Malcolm are inspiring and uplifting, the footage from old racist films and TV shows that ends Bamboozled is extremely disturbing, showing that these supposedly ancient stereotypes and prejudices absolutely still exist in both subtle and obvious ways. Dela’s father, Junebug (the great comedy writer and performer Paul Mooney), sums up the basic question of all three Spike Lee joints discussed above with his eloquent cry of pain: “Why do they treat us like that?”