Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) is a good chap. A good cop, if you must know, and one of the realm’s most dedicated men of principle. He’s the sort who will cite chapter and verse of the legal code, but only after bringing a congregation to its feet in what amounts to the isle’s most piously irritating hobbies. He’s a Christian copper, as described on more than one occasion, and if that means flying his own plane to one of Scotland’s most remote villages in order to find a missing girl, his upper lip is more than stiff enough to suit the matter at hand.

He’s a truth-teller, a crime fighter, a defender of queen and country; and he’ll be damned if he doesn’t wade through the United Kingdom’s thorniest bush of stark-naked folk-singing to find his man. You see, he’s in Summerisle: home of the finest apples in all of Christendom, as well as one of the strangest collections of local eccentrics in a decade not exactly known for its retiring types. Summerisle is a pagan wonderland; a half-crazed, wholly unhinged madhouse of flesh, where the schoolmarms dispense with arithmetic in favor of spirited round-tables on the male organ, and what passes for a doctor sees nothing untoward about having a young child insert a baby frog into her mouth to cure a sore throat. Where Howie sees Christ-like order, Summerisle embraces the chaos.

On its face a horror film with shocking revelations and vice-like tension, Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man is actually study in contrasts; a treatise on modern incomprehensibility in the face of social upheaval. As tradition goes the way of the dodo, primitive barbarity takes its place. Howie, in town only to solve what appears to be an unconscionable crime, is Old England, fanatical in its commitment to legal niceties, but wholly ill-equipped in the face of an even older state of things, which is itself an embrace of the new. As the empire withered and groaned after its peak of mid-century blood and sweat, the disenchanted retreated to the countryside to foster a radical break from the failing godhead of the Union Jack tradition.

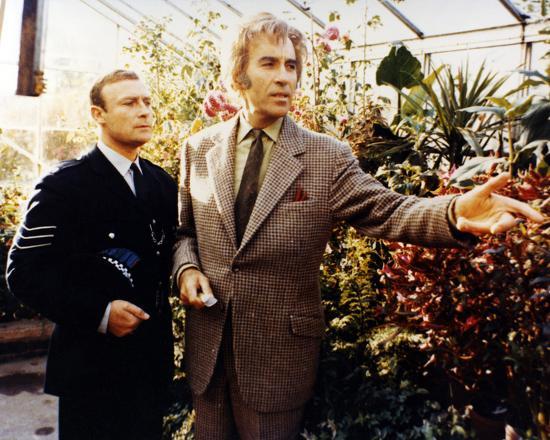

Led by Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee), in possession of an angry charisma matched only by a supremely wicked slab of hair, the community maintains a Potemkin village for prying eyes, yes, but only to distract from the fire-jumping, Stonehenge-stroking dances that all but define life on the margins. Oh, and the fucking – copious amounts of conscience-free, open-air intercourse that all but reduces the good sergeant to a sweaty heap of guilt. He’s a virgin, needless to say, engaged to be married, and though he appears to be at least fifty, he’s held firm all these years. Then again, there’s likely never been a woman like Willow (Britt Ekland) anywhere near his depressing flat.

What can one say about Willow? Hot as a firecracker and unburdened by any respectability whatsoever, she seizes upon Howie’s humorlessness in all the time it takes to expose her Scottish fold. In the film’s most alluringly hilarious sequence, Willow appears naked on her bed, fondling her breasts as she sings her siren song, all while Howie twists and moans in the next room in a flurry of unexpected temptation. And how she dances! Her contortions are inexplicable in any language, though the director is kind enough to bare her ass from a gloriously low angle. She shakes, shivers, and pops; Howie flushes, swallows, and reaches out with the pathetic longing of a man who’s never lived a day. In this way, the savages have clearly won the war, even if Howie keeps his trousers on.

He’s desperate to conquer young Willow, and only an adherence to a silly holy book keeps him from going nuclear. Still, this is a turning point; that last detour before fate settles in and cuts the cards. Had Howie ripped his bedside Gideon to shreds with the straight razor of seminal discharge, burst through the walls like an illiterate ape, and pounded Willow like the inn’s blue-plate chicken, he would have been spared. Soiled and fallen like Lucifer himself, this badge-carrying archangel would have left Summerisle in confusion and doubt, yes, but very much alive. But because he clings to his superstition, the gods of war sun, sea, and stars will have their martyr. As always, sexual repression leads to death as night follows day.

Howie combs the community for any signs of the young girl, but is met by lies, distortions, and bizarre imagery. He’s a pawn in their game, falling ever-so-gently into their tender trap, but he insists on a free will he long ago sold for scrap. Only instead of fulfilling the dictates of his faith, he’s ensuring Summerisle’s survival. Having endured one of the worst apple crops in memory, the town needs to appease the spirits, and no mere child or virgin will do. They need the big guns, and why not a man who lights the briquettes at his own barbecue? We all know where the story is tending, but that makes it all the more thrilling. Howie still fashions himself the keen-eyed detective, when in fact every clue is deliberately dropped for discovery. A rat in a cage, or mouse in a maze, he’s the end game for the new order. In that sense, he’s the last gasp of godly England being set aflame for the brutality to follow.

Removed from regal sensibility, scientific progress, and all the trappings of educated civilization, man is now a brute force for his own glorification; a mincing, dancing, mask-wearing vessel of carnal oblivion, without so much as a written language to tie him down. Summerisle is an eternal sleep-away camp, as if the hippies had stormed the gates at last and found a way to make do in a haze of lounging. Wicker Man is Burning Man writ large, where we dance away the days, gorge away the nights, and time dissipates into a sinking spring of pure pleasure and shrieking bluster. The iron fist of Churchill and Parliament has at last been replaced by Yoko Ono’s bedroom.

Is that it, then, either a solemn Christ or fucking in the streets? The Wicker Man isn’t telling, and who knows whether it’s a canary in a coal mine or a simple “what if” scenario in the Scottish Highlands. For if we are to side with Howie and his confrontation with raw deception, why make him so decidedly unpleasant? We seem to care when we believe a child has been bulldozed for no earthly reason, but once the smoke clears, it isn’t really a closed case that Howie is a victim. His forced immolation at film’s end is more hysterical than hellish, and the cries of the incinerating goat are more troubling than Howie’s eye-rolling roar to his heavenly host. As the flames lick Howie’s flesh, trapped inside the majestic Wicker Man to bid his last, one can’t help but respect the townsfolk, so unmoved by death that they swing their arms in an angelic chorus of love and devotion.

Howie can be Jesus for a day, dying a martyr’s death, and the apples can once again blot out the sky. Winners all around, and we’d be fools for being offended by this ritualized carnage. After all, Howie, despite his modern manners and Biblical morality, is a fundamentally unhappy soul. He yearns, cries, and flaps his flaccidity with a self-righteous thud. Summerisle, on the other hand, prospers in the full light of contentment. Love and laughter and the mighty orgasm run river-like from shore to town center, while Howie stands alone, without even the comfort of an evening’s slide into carnality to ease the pain.